As we approach Candlemas on February 2nd, the traditional end of the Christmas season, I would like to reflect upon this tender portrait of the Madonna and Child by the Austrian-born Catholic painter, Marianne Stokes.

There are so many lovely portraits of the Madonna and Child, I would be remiss to let the season of Christmas go by without writing on one. After all, as

wrote, “the season of Christmas is a many-hued bouquet of praise for the Holy Virgin.”This portrait by Mrs. Adrian Stokes, as she liked to be called, is a Western adaptation of the ‘Eleousa’ or ‘Virgin of Tenderness’ icon, a foundational Marian image which represents the intimate bond between Mary and Jesus. The image beautifully communicates the profound unity between mother and infant, between Mary and Jesus, a closeness which points also to the relationship between God and humanity made possible through the Incarnation.

While Stokes’s portrait is naturalistic in some ways, she has incorporated many symbols from the sacred aesthetic canon and used tempera paint which imparts on the painting a heavenly glow. It’s quite a striking work of art. The bond between Mother and Child is so palpably delicate, and Mary’s gaze contains multitudes.

Her attention is so singularly devoted to her newborn child, as a new mother’s attention is wont to be. Meanwhile, Jesus nestles up next to his mother’s cheek, his tiny and adorable face resting on her chest. In this portrait, Christ’s small body has a distinctly earthly corporeality. And yet his cruciform halo and his mother’s red-rimmed halo point to the fact this is no ordinary Mother and Child.

Here, Mary and Christ seem to glow with an otherworldly serenity. Their clothing accentuates this serene beauty. Christ wears swaddling clothes, which point to his death and burial as well as to the bonds of love. Mary wears a blue cloak, symbolizing the Divinity that overshadowed her, and a light pink garment symbolizing her humanity. The azure blue of Mary’s cloak shines so luminously because of the tempera paint Stokes used. Iconographers Gothic artists used this notoriously unforgiving paint made from egg yolk to bring a Heavenly sheen to images of Christ and the Saints.

Joy mingles with sorrow in this painting of the Madonna and Child. Mary’s loving yet somber gaze reflects her compassion for her son and her recollection of his sorrowful death. Even as a new mother, Mary knew that her divine motherhood will bring about grief as well as joy. As Simeon said to her, “a sword will pierce thy own heart.” In many icons and paintings of the Nativity, Mary is depicted with this sorrowful gaze. The image of Christ asleep in his mother’s arms also points to images of the deposition and the Pieta where she holds her son again.

Mary’s hands also feature prominently in this portrait and are perhaps a part of why so many find this portrait so emotionally resonant. A mother’s hands are a profoundly evocative spiritual symbol of her compassion and desire to protect, but also of her human fragility. Even Mary could not protect her son from death.

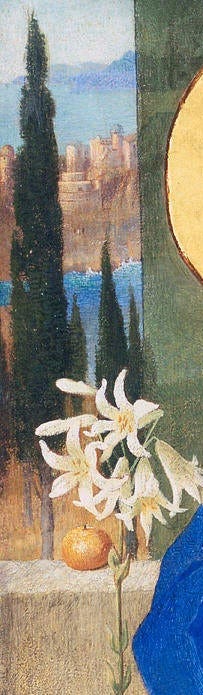

Stokes depicts many other symbols that are part of the Christian artistic cannon. As I mentioned in an earlier article on her, Marianne Stokes was a devout Catholic and in an interview, revealed that her aesthetic imagination was formed by the liturgy. Notice the orange, the swaddling clothes, the lily, the wall, the cypress trees and the city behind Mary.

Oranges are a traditional Christmas symbol which remind us that Christ is the sun, the Light of the World. Oranges also recall the apple from the garden of Eden and Marian oranges reflect Mary’s role as “the new Eve.”

The walled garden, the “hortus conclusus” is an image from the Song of Songs which points to Mary’s virginity, “My sister, my spouse, is a garden enclosed, a garden enclosed, a fountain sealed up.”

The green cloth which hangs behind the Virgin reminds us of the role of the Spirit in Christ’s birth, for it was the Spirit that came over her when the Angel came.

The city behind the Mother and Child represents the Heavenly City, the kingdom brought forth by Christ in the Incarnation.

The cypress trees represent death and mourning and have been used in funerary imagery for thousands of years. In the Christian tradition, their evergreen leaves and long-upward pointing stature also point to eternal life in the resurrection. The cypress tree also points to the cross, which was said to be made partly of cypress wood.

Finally, the white lily represents Mary’s purity and virginity. It also represents Christ himself. As the lily spends three years in the ground before blooming, Christ spent three days in the tomb before his resurrection. Saint Bede says its trumpet-like shape heralds Christ’s Resurrection as well as the return of spring.

In Mary’s compassionate gaze we see all of these symbols poetically harmonized. She looks upon Christ’s birth, death, and Resurrection and beyond to eternity where she continues to live in this close embrace with Christ her son.

For more on Marianne Stokes see:

A forgotten Victorian painter, Saint Elizabeth of Hungary, and the Holy Face

Despite being one of the most prominent painters of the Victorian period, Marianne Stokes is largely unknown today. She has a few recognizable paintings—her painting of the Madonna and Child …

Beautiful! Thank you so much for introducing me to a new painter, a beautiful painting. And for the lovely explication. I am familiar with much of the language of religious paintings, but there are always details I miss-- like I didn't notice the wall and I didn't recognize the cypress trees.

I have a tiny icon of the Virgin of Tenderness on my desk at work. It is a consolation. ❤️ Beautiful to read about Stokes’ piece.