Despite being one of the most prominent painters of the Victorian period, Marianne Stokes is largely unknown today. She has a few recognizable paintings—her painting of the Madonna and Child was on a Christmas stamp in 2005—but by and large she doesn’t have much name recognition. Most of her paintings are in private collections making it difficult to access her work, and her earnest religiosity confounds art historians.

After growing up in Austria, Marianne Stokes, nèe Preindlsberger, studied in Munich and began her career in Paris. While in France, she painted as the Parisian realists did, with mostly muted colors and oil paint, but after meeting her husband, the landscape painter Adrian Stokes, she turned to a much more colorful style.

The Victorian Catholic literary critic, Alice Meynell, explains the reasons for this shift:

Her first conviction of the greatness of colour was gained when she was ready for it, in the galleries of Italy, and in the study of the primitive painters who seem to look not against the light, so as to see the shadows of a luminous world, but with it, so as to see the colours of an illuminated world.1

Like the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Stokes was drawn to the simplicity and spirituality of the Gothic. With them, she admired the brilliant color and the unity of form and matter in the Italian quattrocento. However, unlike most Pre-Raphaelite artists, whose devotion to the Gothic period was mainly aesthetic, she was a devout Catholic, and she aimed to revive in her art sincere religious devotion. Stokes’s religious paintings are infused with the warm radiance of faith, and clear symbols and narratives.

Like the Pre-Raphaelites, she also took up tempera, a paint made with egg yolk, known for its unforgiving, quick drying nature. The way tempera is layered gives the colored paint a jewel-like quality and that luminous shine. She favored this paint especially in her religious works.

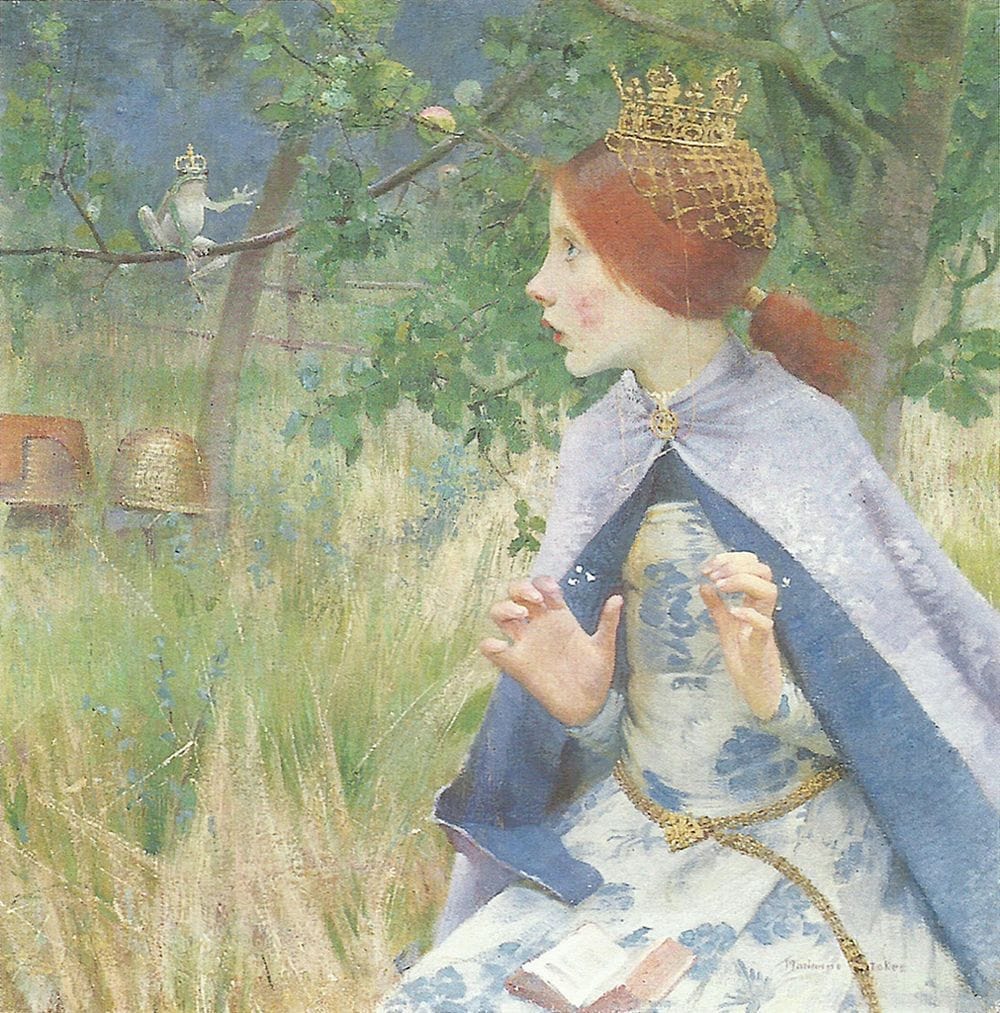

Mrs. Stokes’s “conversion to color” as the Catholic literary critic Alice Meynell put it, was not only prompted by her voyage to Italy, but rooted in experiences from her childhood. In a magazine interview from 1900, Mrs. Adrian Stokes, as she liked to be called, revealed the two most important aesthetic influences on her art:

One is a volume of Grimm's "Fairy Tales," given to her as a child, with illustrations of sufficient artistic quality, quaintness of humour, and fineness of line not to be harmful: "It might have been so much worse," says Mrs.Stokes.

The other, and the more important, is the fact of having lived in a Catholic country. The Catholic ceremonial appealed strongly to the aesthetic part of her mind, so much so that her feeling for, and delight in, colour, with a dash of mysticism in her later work, have had their origin in the pleasure derived from the processions, the lights and the vestments of the Church.2

It wasn’t just the colors she appreciated in these processions, but the exquisite craftsmanship of the vestments. I found this summary of the Arts and Crafts movement from

’s recent piece helpful for understanding the context of her painting style:Morris and his contemporaries embraced the medieval aesthetic as a form of protest against mass-produced goods, echoing Pugin’s belief in the moral value of beauty and craftsmanship. They extended this philosophy into furniture, textiles, and books, all designed to create a holistic cultural environment that fostered beauty in everyday domestic life - furniture, wallpapers and carpets, embroideries, tapestries, tiles and book designs.3

Marianne saw her own work in this vein, as “beautiful decoration.” She loved to paint women working at the loom or hearth, highlighting the noble dignity of their work and the delicate skill it required.

In 1905, shortly before World War I, she and her husband traveled to Hungary to paint and record the traditional ceremonies and dress of Slovakian people.4 This record became quite important after the Hungarian culture was decimated by World War I. In this book, she continued to paint images of women and children sewing, praying and working.

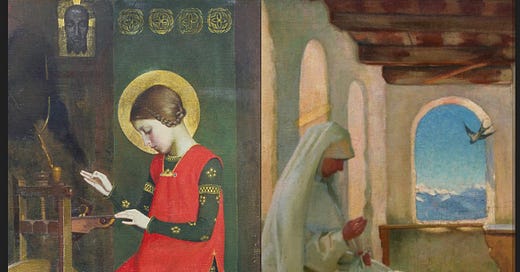

“The first picture that aimed at both pure decoration and pure spirituality was Saint Elizabeth spinning for the Poor.” —Alice Meynell

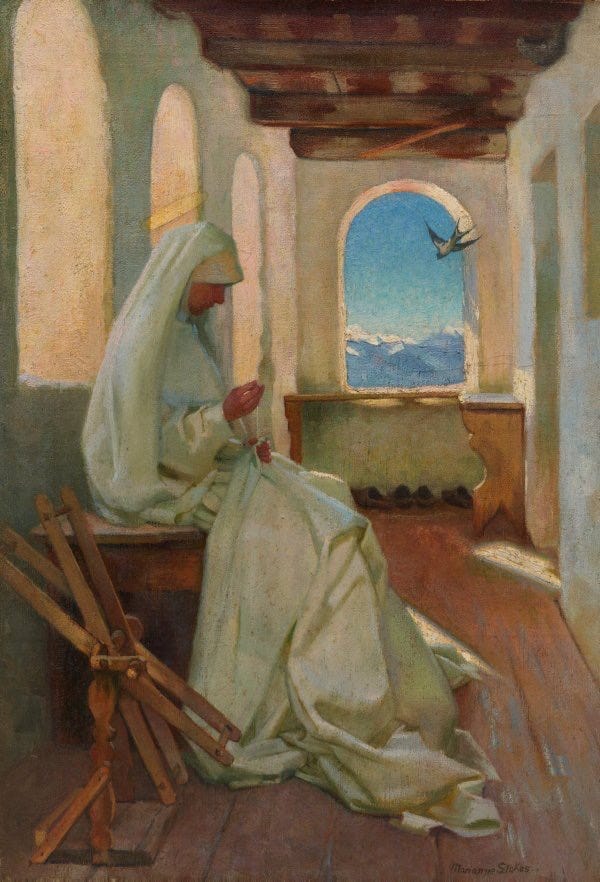

In Saint Elizabeth of Hungary, Stokes found a saint who served God through the beauty of her craftsmanship. She painted Elizabeth once in 1895 and returned to paint the saint again in 1905. Both portraits highlight the contemplative beauty of the saint and her work.

Some art historians have connected the painting of Saint Elizabeth spinning to Roger Van der Weyden’s portrait of Mary Magdalen reading. This connection reveals the way Stokes understood the act of spinning as a contemplative one, because of the way it united the whole being of a person to one single act of creation.5

In the 1895 portrait, a flat gold halo surrounds Elizabeth’s head, pointing to the holiness which shines through the innocent purity of her luminous face. Although Saint Elizabeth grew up as the privileged daughter of a King, she made great efforts not to let her soul be weighed down by worldly comforts, and from a young age devoted herself to prayer and serving God in the corporal works of mercy.

The radiant red of Elizabeth’s tunic and the gold leafed pattern which adorns her clothing highlights her royal status as a princess of this world and also as a saint. The rustic loom she works seems to contrast with her luxurious clothes, but the work she does exemplifies her industriousness and feminine virtue, recalling Proberbs 31:19, "She puts her hand to the distaff, and her hands hold the spindle."

Recalling this verse, we remember that Elizabeth was wife to the noble Ludwig, who admired her piety and supported her almsgiving. Once, Ludwig found Elizabeth taking care of a leper in their own bed. Instead of responding with disgust as many would, he experienced a vision and remarked, “Dear Elizabeth, it is Christ whom you have cleansed, nourished and cared for.” Afterwards, he always encouraged her charitable works and offered to build her a hospital so that she would have plenty of room to take care of the sick.

While the loom points to her womanly virtues, it also brings to mind countless stories of Elizabeth clothing the poor. In the Golden Legend, Jacob De Voraign recounts how she would frequently take on the role of godmother for poor children, sewing for them the finest baptismal gowns. Later in life, Elizabeth sewed gowns for the patients in the hospital she founded.

From the shadows of the painting, the Holy Face of Christ shines upon Elizabeth recalling that the face of God is a sign of blessing, mercy and consolation throughout the Bible.

“The Lord bless you and keep you. The Lord make his face to shine upon you, and be gracious to you. The Lord lift up his countenance upon you and give you his peace." Numbers 6:22-27

As the holy men and women of the Old Testament sought the face of God through their trials, so Elizabeth sought the face of Christ through her suffering. In the painting above, her face even resembles his peaceful countenance.

“Now there was a famine in the days of David for three years, year after year. And David soungth the face of the Lord.” (2 Samuel 21:1)

This particular image of the Holy Face comes from the cloth Veronica impressed upon the face of Christ as he walked to his Crucifixion. The way it hangs in the shadows seems to foreshadow the many sorrows Elizabeth would undergo after the death of her beloved husband and point to Christ’s presence throughout her suffering.

Shortly after Elizabeth delivered their third child, she received news of her husband’s death, and was forced out of the castle by her husband's greedy brother who also stole her dowry. During this time, Elizabeth and her three children found shelter in a pigsty.

Eventually, with the support of her uncle, she won back her rightful inheritance, and used it to found a monastery with an attached hospital. Elizabeth lived out the last three years of her life as a third order Franciscan at this monastery, tending to the sick and needy. When she spent up her dowry serving the poor, she sewed clothes to make money to sustain the hospital.

The face of Christ is not only a symbol of Elizabeth’s suffering, but of her final end in the Beatific vision. “They will see his face.” (Rev 22:4)

In the later portrait, Elizabeth is also portrayed sewing clothes for the poor. The luminosity of the blue sky and snow capped mountain shine through the windows of the white balcony. Bathed in light, her white habit, contemplative gaze, and the translucent halo atop her head convey a heavenly peace. A bird, which symbolizes the presence of the Holy Spirit flies through the window.

By looking at these works together, we are struck by Elizabeth’s peace, constancy, and contemplative focus. In both scenes, she sits in nearly the same pose, devoutly focused on her holy craft in everyday labors. Notably, the spinning wheel and other wood in the paintings do not resemble a cruciform shape, and yet it still calls to mind the wood of the cross and the many crosses Elizabeth bore throughout her life. At the age of 24, she died of a fever, likely catching it from one of the patients from her hospital. In this second portrait and on today’s feast, we are invited to contemplate how Elizabeth’s labors and suffering have been transformed into heavenly peace and Glory.

Meynell, Alice. "Mrs Adrian Stokes." The Magazine of Art Vol. 25 (1901): 241-46. Internet Archive.

Harriet Ford, “The work of Mrs. Adrian Stokes.” The Studio, vol. XIX, n. 85, 1900, p. 18. https://books.google.com/books?id=mymhDlWLCtEC&pg=PA149&dq=%C2%A0Harriet+Ford+%22The+work+of+Mrs.+Adrian+Stokes.”&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&source=gb_mobile_search&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiHjvGQ8OOJAxVBTTABHTxSH_wQ6AF6BAgFEAM#v=onepage&q=%C2%A0Harriet%20Ford%20%22The%20work%20of%20Mrs.%20Adrian%20Stokes.”&f=false

https://substack.com/@hilarywhite/p-151219411

You can find the book on the internet archive: https://archive.org/details/hungary00stok

Jan Marsh and Pamela Gerrish Nunn, Pre-Raphaelite Women Artists (Manchester: The Galleries, 1997).

I am always delighted to discover artists such as Marianne Stokes, who, in the heart of the modern world, have strived to maintain continuity with the old and wise Sacred Aesthetic Canon. Thank you for this article!

Brilliant as always.

Her first painting of Elizabeth feels like it is plucked right out of medieval/Gothic style, and the latter as something a touch more "modern." Almost like subdued Renaissance (if I had artistic vocabulary I'd say this better).

Thank you for a grand exploration!