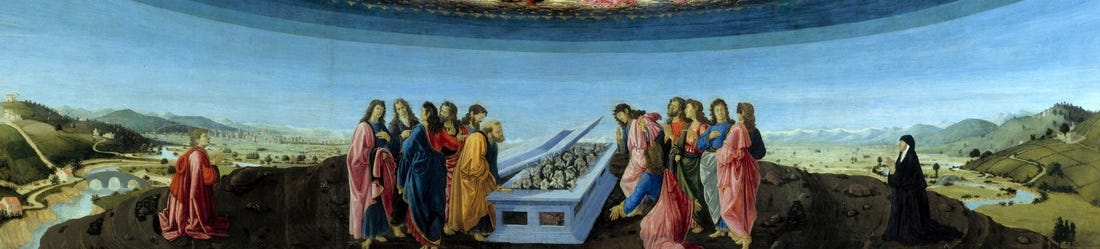

The most striking thing about this enormous painting is its arresting luminosity. In person, the painting quite literally lights up a room.1 To those who contemplate it, Francesco Botticini gives a glimpse of the splendor of Heaven.

Initially, the majestic painting hung in a south-side chapel of the ancient church San Piero Maggiore, which was founded by the first bishop of Florence in the fifth century2. The painting was meant to hang relatively low, below where the nuns' choir would have been, illuminating the sisters with the radiant light of Heaven. However, the painting never hung where it was meant to, and instead hung as the altarpiece for a prominent side chapel, which would have been visible upon entering and exiting the Gothic church. 3

The radiance of the gilded dome draws attention upward to where Christ welcomes Mary his mother, body and soul, into the splendor of Heaven, where she shares the glory of her Son’s resurrection.4

Four concentric circles of light surround the figure of Christ while golden bands of light holding the nine tiers of angels compose the dome of heaven. Saints mingle with the angels and include such recognizable figures of Adam and Eve, David, Saint Jerome, Bartholomew, Saint Lawrence, Saint Augustine.

A quote from the eleventh-century bishop and martyr Saint Gerard, included in the Golden Legend, describes the jubilant scene:

The heavens welcomed the Blessed Virgin joyfully: Angels rejoicing, Archangels jubilating, Virtues honouring, Thrones exalting, Dominions psalming, Principalities harmonizing, Powers playing their lyres, Cherubim and Seraphim hymning and leading her to the supernal tribunal of the divine majesty.

The harmonious arrangement of bodies and colors in Botticini’s painting echoes the harmony of the heavenly hierarchy of angels described by Saint Gerard; The orderliness of the painting inspires confidence in the unity of God’s plan for all things.

This luminous splendor also recalls the radiance of the Transfiguration, which was celebrated only a little over a week ago. It’s not a coincidence that these two feasts are placed close together in the Church calendar. Both feasts point to the Resurrection of the body and God’s plan for our own bodily redemption.

Pope John Paul II explains:

Her Assumption into heaven is not only the culmination of her particular vocation as the Mother and disciple of the Lord Jesus but also an eloquent sign of God's fidelity to the universal plan of salvation aimed at the redemption of every man and of all men.

The drapery of the saints and angels grows increasingly luminous the closer they get to Christ. So, the clothing of the third ring of saints and angels is significantly less luminous than the saints in the ring closest to Jesus, whose clothing shines with a golden sheen. Mary’s clothes shine most luminously of all behind Christ’s. As Dante (1265-1321) says in the Divine Comedy, a poem that almost certainly influenced this painting: “The glory of the One who moves all things penetrates the universe with light, more radiant in one part and elsewhere less.” (Paridiso 1:1)5

Although the saints and angels share in Christ’s splendor, only Mary gazes directly at God himself. Even we as viewers do not see his eyes in this painting. Mary kneels before her Son with her hands closed in prayer and gazes directly at his face as he blesses her. The open book on his lap shows the Greek letters Alpha and Omega, the Beginning and the End.

This image of Christ as the Word and the Light calls to mind the prologue of John: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by him: and without him was made nothing that was made. In him was life, and the life was the light of men. The Light shines in the darkness and the darkness has not overcome it.”

In this painting, Botticini reveals Christ as the Word who gives Light and Life to all of creation. This connection would not be lost on Renaissance viewers who would have heard the prologue at the end of every mass and who also would have understood the connection between creation, Heaven, and light.

Anthony Esolen, who translated the Divine Comedy, explains the connection between “from ‘be’ to ‘shine.’” (Paridiso 29:27)

To create from nothing is to impart being itself, and to bring forth from darkness is to impart light. We are to see here an intimate relationship between existence and splendor: between the act of being, and the pouring forth of light.

The idea that “God is light” pervaded the medieval world. The entire structure of a Gothic church was built around a theology of light and churchgoers were regularly treated to elaborate mystery plays which also emphasized this connection. In fact, this painting is often likened to the domed sets used for these Florentine “Paradisi” plays6, one of which was described by Russian Bishop Suzdal in 1439:

A throne on which a man of majestic appearance is seated, dressed in a priestly robe with a crown on his head and the Gospel in his left hand, as God the Father is represented. He is surrounded by many children artfully arranged around him with 500 little oil lamps... There were [on the spheres of heaven] a thousand lit oil lamps... All this represented the seven heavens, the heavenly powers, and the inextinguishable angelic light.

These “Paradisi” directly drew on Dante’s description of Paradise in the Divine Comedy. It’s hard to overstate Dante’s popularity in Florence at the time of this painting. His portrait even hung in the cathedral.

Notably, in Botticini’s painting Mary does not face the viewer; we mostly see her back. Mary directs us to look at her Son. This portrayal of Mary reflects a truth about her explained by the late Norbertine priest Fr. Cadoc Leighton:

Closeness, in the spiritual realm, ... is similitude. The Second Person of the Blessed Trinity has become one like us, so that we can become like Him. In [Mary's] life we see the process of our redemption revealed, because we see her similitude to her Son. We cannot actually contemplate Mary without contemplating Jesus at the same time.

So, in this painting, Mary’s Assumption directs us to contemplate the Divine Light of Christ, which is not contained only in the heavenly dome of the painting but emanates to the landscape below where the apostles gather by Mary’s empty coffin, which is filled with lilies symbolizing her purity. The light of God’s glory fills all things and allows us to see.

This mountain also recalls other times God revealed himself on mountaintops, such as at Sinai to Moses and Elijah or at Mount Tabor in the Transfiguration. Florentine churchgoers would have also probably understood this mountaintop to represent the garden of Paradise, featured in Dante’s Purgatorio. Unburdened by their sin, those who summited the mountain of Purgatory gathered and drank from the two rivers Eunoë and Lethe, before shooting up to heaven.

On either side of the apostles are the patrons of the painting, Matteo and Niccola Palmieri.7 A classic “Renaissance man,” Matteo (1406-1475) owned an apothecary business, served in public life, and wrote works of poetry, including one inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy. Botticini painted a small portrait of the city of Florence behind his portrait.

Although the apostles and the patrons appear physically close to the heavenly dome, even the earthly paradise appears a world apart from the heavenly splendor experienced by Mary. In this painting, Botticini invites all of us to imagine ourselves having summited Mount Purgatory, praying with Matteo and his wife, that like Mary we too may see that “Living Light” face to face some day.

At the end of the Divine Comedy, it is Mary’s eyes that direct Dante to the Beatific Vision, of which he exclaims:

“O Light that dwell within Thyself alone, who alone know Thyself, are known, and smile with Love upon the Knowing and the Known.” (Paridiso 33:124)

Ultimately Mary points to our end and helps us to behold God in the light of love and, in beholding, become like him.

Sadly it is currently off display.

The National Gallery bought it in the 1800s when it was thought to be a Boticelli piece. It was bought after the duke of Florence rather opportunistically tore down the church after a column collapsed during renovations. Art historians began attributing it to Botticini after they discovered the drawings and under drawings he did for the painting.

The tradition that Mary was assumed into Heaven can be traced back to the 6th century and has been celebrated in the Church for centuries. It was formally defined in 1950 as an article of faith by Pope Pius XII.

Esolen’s note on on this verse: “Dante follows the long medieval and patristic tradition, whereof the work of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite is the most notable example (see 10.115-17 and note), of holding that of all created things, light is the closest in nobility to God. This light is not merely physical, though it is at least that; it is also and more fundamentally intellectual light, a spiritual creation (cf. Augustine, Confessions 13.3). It is the light of God's glory that fills all things, that gives them their very being by filling them Jer. 23:24). That the glory of God shines in varying degrees in various objects is a commonplace of medieval thought (cf. Pseudo-Dionysius, Divine Names 872A) and is one of Dante's most insistent themes, as he will assert that the structural complexity and inner harmony of the universe are expressed by means of these differences. That there is a hierarchy among the blessed is implied if not asserted by Christ himself. "In my Father's house there are many mansions" (John 14:2); "Whosoever therefore shall humble himself as this little child, the same is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven" (Matt. 18:4).

https://www.artes-exhibition.digital/the-heaven-machinery/

Palmieri’s face was scratched out of this painting for years because his posthumously published poem contained some heretical ideas about the soul that he learned from Origin. In his poem the soul begins in heaven as an angel and has to descend down to earth. Although Palmieri had some influence over the painting, it does not appear like this idea is shown in the work.

I am so enjoying these meditations. This is one I have never seen. Beautiful.

Thank you, Amelia.

Just beautiful, I love Mary’s delicate crown, the Queen of Heaven 😇🙏🙏