It’s hard to overstate the importance of Gregory the Great for the history of the Church and the West. Gregory was born into an illustrious Roman family that had survived the ravages of barbarians and plagues. As a young man, he served as prefect of Rome, but after his father died, Gregory used his family inheritance to found multiple monasteries, one of which he was a monk in before being selected as Pope. As a monk, he wrote the first biography of Saint Benedict of Nursia and as Pope, he sent the first Christian missionaries to the Anglo-Saxons, Franks, and Gauls.

Pope Pius X once remarked:

The whole medieval period bears what may be called the Gregorian imprint; almost everything it had indeed came to it from the Pontiff – the rule of ecclesiastical government, the manifold phases of charity and philanthropy in its social institutions, the principles of the most perfect Christian asceticism and of monastic life, the arrangement of the liturgy and the art of sacred music. (Pope St. Pius X, Iucunda Sane, 12 March, 1904)

It is fitting that the most famous artistic depiction of this saint is at a Mass, for Dom Gueranger calls him the Great “Apostle of the Liturgy.” Gregory’s liturgical reform was not one of invention but of clarification. He reduced the number of extra prayers and arranged the Roman Canon to the form that survived the millennia to the modern day. Gregory also helped develop a standard Gregorian chant which is based on the ancient way the psalms were chanted, and he founded a Schola to ensure its implementation.

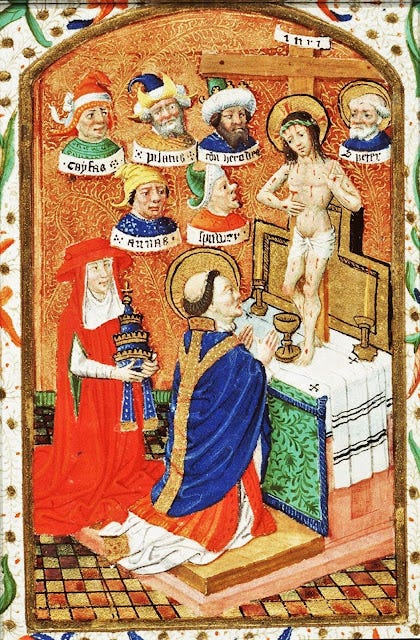

Fifteenth-century artists painted the Mass of Saint Gregory on various mediums—illuminated manuscripts, altarpiece panels, small devotional panels, and private missals. Although there are differences in the details, they all seem to encourage devotion to Christ in the Eucharist, namely by emphasizing the sacrifice of Christ memorialized in the Mass and by highlighting Gregory’s devotion and reverence.

I saw this particular painting at the Getty Center this Christmas while visiting family in California. Although it is a rather small devotional image, it is meticulously rendered and quite impressive.

The story of the miracle that inspired this image was recorded by Gregory’s first biographer and retold in the Golden Legend:

A certain woman used to bring altar breads to Gregory every Sunday morning, and one Sunday, when the time came for receiving communion and he held out the Body of the Lord to her, saying: 'May the body of our Lord Jesus Christ benefit you unto life everlast-ing; she laughed as if at a joke. He immediately drew back his hand from her mouth and laid the consecrated Host on the altar, and then, before the whole assembly, asked her why she had dared to laugh.

Her answer: 'Because you called this bread, which I made with my own hands, the Body of the Lord!

Then Gregory, faced with the woman's lack of belief, prostrated himself in prayer, and when he rose, he found the particle of bread changed into flesh in the shape of a finger. Seeing this, the woman recovered her faith. Then he prayed again, saw the flesh return to the form of bread, and gave communion to the woman.

Isenbrandt’s painting reflects a different gloss on the original story. In his painting, Christ appears to Gregory as the Man of Sorrows, along with the Arma Christi, the instruments of torture that become the weapons Christ used to defeat Satan. This popular rendering of the miracle seems to be an artistic combination of Gregory’s Eucharistic miracle with his devotion to the Man of Sorrows1, to whom he wrote many devotional prayers. This visual synthesis highlights the theological reality— that Christ’s corporal presence in the Eucharist is the fruit of his Passion which is memorialized in the sacrifice of the Mass. A reverent liturgy, such as the one depicted here, helps makes this profound mystery apprehensible.

This particular version of the Gregory Mass stands out among the hundreds of variations, although it appears slightly cluttered initially. Even in this solemn moment, there is life and movement. The torch leans back precariously; the deacon swings the thurible, incensing the altar; congregants in the background point away distractedly; the abundant cloth of the white albs flows and billows on the ground; architectural flourishes swirl and fume. All of the movement intensifies the drama of Gregory’s vision.

Amidst all of this, Christ appears to Gregory moments before the consecration with his hands raised in solemn prayer over the altar and congregation. He directs the blood flowing from the wound in his side into the chalice. Meanwhile, Gregory’s constant gaze is fixed on Christ, who stands outside his tomb showing that he has triumphed over the grave while also drawing attention to his wounds.

Here, Jesus is surrounded by the instruments of his torture, including the hammer used to nail him to the cross, the spear that pierced his side, the lantern used to find him in the garden, the sponge used to offer him vinegar and gall, the pincers and the ladder used to take him down from the cross and the rooster which alerted Peter.

Isenbrandt paints Gregory in an ornate liturgical context flanked by a deacon and subdeacon who wear dalmatics, the same vestments they would have worn in Gregory’s day2. They hold Gregory’s chasuble and a torch. A cardinal, sometimes understood to be Saint Jerome, kneels and follows a missal behind the altar. He seems to model a kind of prayerful attention for the viewer, but even he does not see the vision of Christ. Gregory’s papal tiara sits at his feet.

Jerome, Augustine, and Ambrose are often pictured together with Gregory in this image, not because they lived at the same time but because they were, together, the four Great Latin Doctors of the Church. The Bishop in the background probably represents one of these great saints.

Notably, the vestments are given considerable detail and are the most eye-catching aspect of the painting. They are truly resplendent. In one manner, they seem to glorify the men in their priestly identity, and yet it is a properly ordered glory because it is all intensely ordered toward giving glory to Christ. One detail that is striking when one focuses on the priests’ vestments is Christ’s stark nudity in comparison. During the Mass, in order for the priest to be in persona Christi, he must cover his own inadequacies. This is similar to Adam and Eve covering themselves in garments of skin after being banished from the Garden. Christ, being the new Adam, needs no such covering. He alone is the perfect priest and perfect sacrifice. The priests’ hair too, being cut in the traditional tonsure (shaved on top), is a mark of their humility as they bare their heads in an unflattering manner. The whole work in all glory and beauty paradoxically inspires the viewer to the great virtue of Humility.

In the Gregory Mass paintings, the Pope wears a traditional chasuble with the embroidered cross which represents the way he must put on Christ's yoke. As a priest puts on the chasuble, he prays “O Lord, Who said: My yoke is sweet, and My burden light: grant that I may be able so to bear it, that I may be able to obtain Thy grace.”

Gregory’s devotion to Christ in the Eucharist, which Isenbrandt portrays in his painting, is also revealed in the reverence and precision with which he cared for the Mass and its music. His liturgical reforms and Gregorian chant continue to nourish the Church today.3

The painting still works as an invitation to see beyond the appearance of the Eucharist to the body and blood of Christ himself. Gregory’s vision can still help us to train our eyes to see Christ and his sufferings in Mass on the altar, even when the reality remains veiled to us. As Saint Augustine says, “What you see is the bread and the chalice; that is what your own eyes report to you. But what your faith obliges you to accept is that the bread is the body of Christ, and the chalice is the blood of Christ.”4

https://www.themorgan.org/collection/hours-of-henry-viii/174

“The dalmatic, so-called because it came from the Greek province of Dalmatia,[18] was introduced in Rome in the second century.[19] It was an ample tunic with large, short sleeves, suitable for those who were obliged to move about. The garment thus became very useful and common among bishops and deacons. In the Acts of the martyrdom of St. Cyprian, we can see that this saint left his mantle to his executioners and gave his dalmatic to the deacons.[20]….

The deacon Hilary, authors of the questions on the Old and New Testaments which he wrote about three hundred years after the conquest of Jerusalem, or around 365, says that the deacons and the bishops both wore the dalmatic.[21]St. Isidore, in the 6th century, regards the dalmatic as a sacred garment, white, and decorated with purple bands.[22] Remigius of Auxerre describes it as a white garment with red bands.[23] This is how the deacons’ dalmatic became a garment of solemnity that was meant to inspire holy joy, in the expression of the Pontifical.[2”

https://sicutincensum.wordpress.com/2018/04/16/on-the-chasuble-stole-and-dalmatic/

Even in the Novus Ordo, the Roman Missal still recommends Gregorian chant take “pride of place,” though sadly that is hardly the case in most parishes. In my opinion, it is one of the most effective ways to deepen a congregation’s reverence during worship as its very nature and strangeness bears witness to the mystery that takes place.

https://www.earlychurchtexts.com/public/augustine_sermon_272_eucharist.htm

We are rooted to a Living Vine, adorned with heroic saints and powerfully simple offerings. St. Gregory the Great, pray for us....

Grace and Peace to you sister, Saint Gregory the Dialogist and Pope of Rome is Commemorated on March 12th in the East. ☦️ 😌⛪ His DIVINE LITURGY of Presanctified Gifts 🔥 is Sung during Weekdays of Great and Holy Lent. The ✍🏼 MORALS on the BOOK of JOB, and his Vita of Saint Benedict of NURSIA 🇮🇹 are patristic staples 📚 for ALL 🌐 believers. ST GREGORY the Great, Pope of Rome, pray for us!