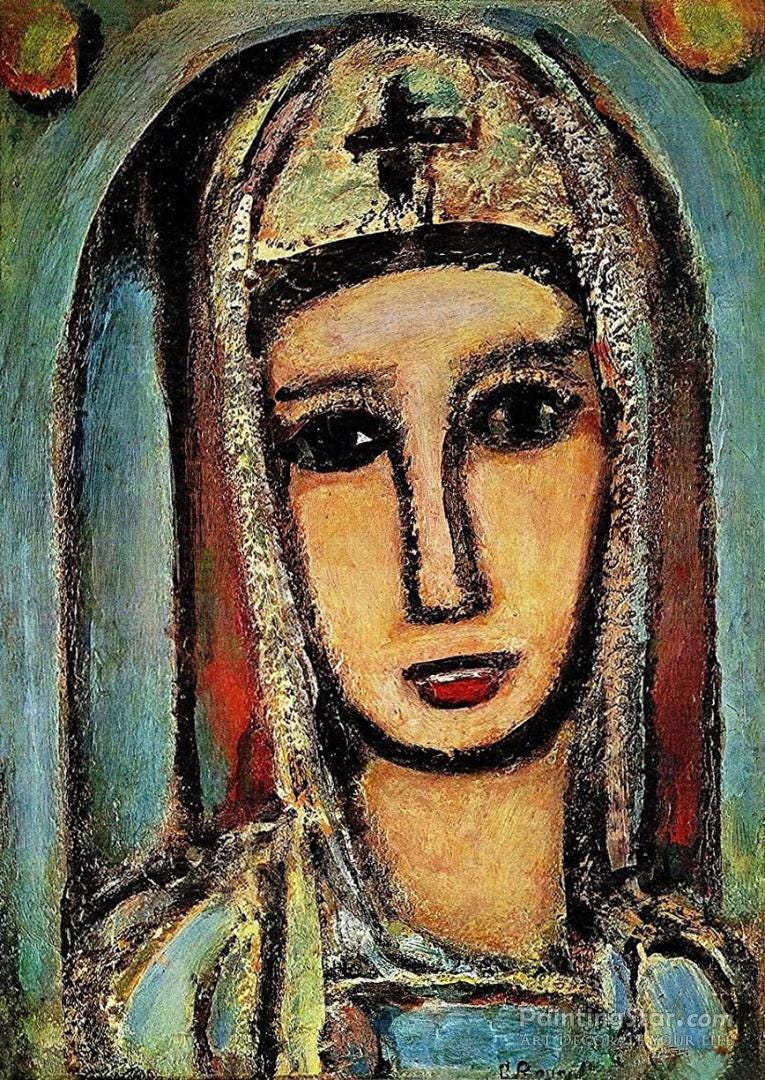

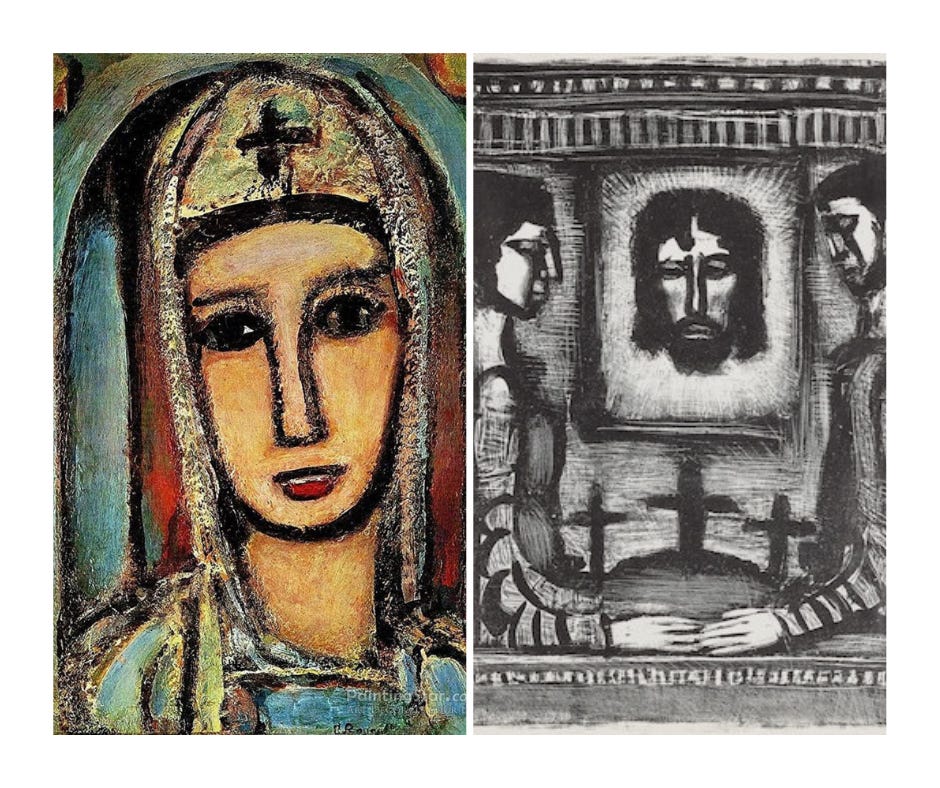

Some images are so powerful that they implant themselves in the mind, and the heart cannot seem to shake them. In the great Catholic painter Georges Rouault’s case, one such image was Veronica’s veil implanted with the face of Jesus. It is a very fitting miracle for an artist to contemplate, which is something Rouault certainly did for several decades, as he painted her veil over and over throughout his life.

In the tradition, Veronica finds Jesus as he carries his cross to Golgotha and, in an act of compassion, offers him her veil to wipe his face. When he returns her veil to her, it is imprinted with his face. Fittingly, Veronica’s name means “Vera-icon, or true image,” and her original name was said to be Seraphia. There are many accounts of healing miracles associated with the veil, but the story is best known for its place in the Stations of the Cross.

Rouault seemed to view Veronica as his model artist that he sought to emulate, even though she was technically not an artist. She did not create the imprint of Jesus’s face. The veil is an acheiropoietos—not made by human hands. Rather, it was something received as a gift of divine grace.

He saw Veronica as a master of seeing. Unlike so many who shrunk away from Jesus in the moments leading up to the Crucifixion, Veronica sought Jesus even as he was veiled by the gruesome ugliness of his suffering. She looked past the notion he was just a common criminal and recognized him and, in so doing, revealed him to others in his Glory.

In this moment, Veronica couldn’t yet understand the meaning of the Cross or the light of the Resurrection. She knew she couldn’t stop the Crucifixion or Christ’s suffering; however, she could wipe his brow.

Rouault believed the artist's task was one of seeing rightly and responding in love. Like Veronica and his artistic mentor Gustav Moreau, Rouault aimed to turn back the veil and see past the outward appearances of his subjects in order to present the spiritual truth.

He put it this way in a letter to French author Eduard Sure: “Be he King or Emperor, what I want to see in the man facing me is his soul, and the more exalted the position, the more I fear for his soul.”

Unlike his colleagues whose art became more and more abstract, Rouault believed that spiritual truth was anchored in the visible world. He expressed frustration with abstract art, which he believed cut itself off from visible reality.1

Although Rouault is often grouped with the Expressionists or the Fauves because he shares some of their stylistic characteristics, his art defies these categories. As a teenager, he trained as an apprentice for a stained glass maker, which is where he says he developed a “passionate taste for color.” It’s clear that the iconic style and subject matter of the glass stayed with him throughout his career.

“The imprint of Christ's face on Veronica's veil, which Rouault never tires of depicting, seems to mean for him the imprint of divine mercy on human art.”—Jacques Maritain

The Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain, a good friend of Rouault’s, saw a kind of realism in his art:

This kind of "realism" is in no way realism of material appearances…Rouault's realism is transfigurative, and it is one with the revealing power and poetic dynamism of a painting which remains obstinately attached to the soil while living on faith and spirituality.

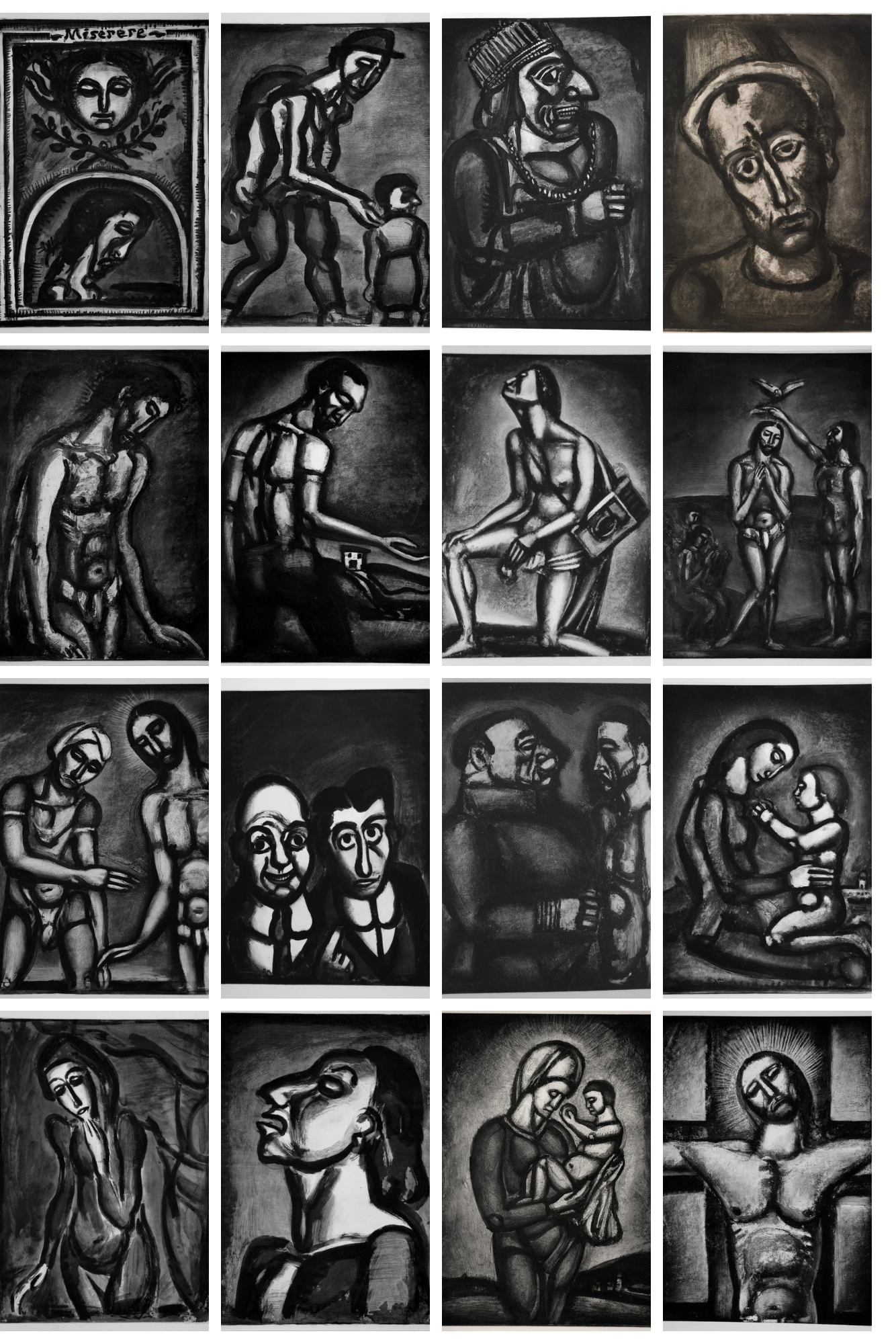

In what is widely considered his masterpiece, the Miserere et Guerre/Have Mercy and War, Rouault created a set of 58 copper plates reflecting on the horrors of World War I and the misery he experienced growing up next to a brothel in a rough part of Paris.2 In Miserere, all of this darkness is put up to the light of Christ’s mercy. The title comes from Psalm 51, a penitential plea for forgiveness.

Themes of “hardness of heart over against humility, cruelty over against compassion, pomp over against poverty” recur and converse, as do certain gestures and facial expressions. Veronica’s veil stands as the central image in the series, recurring five times as the last plate of the first set of images, the first and last plate of the second set, and two other times.

In this symphonic work, Rouault juxtaposes images of Christ with images of sorrowful clowns, downtrodden prostitutes, wayfaring refugees, loving mothers, haughty society-women, callous judges, and other ordinary people suffering the ravages of war. It’s helpful to understand the host of characters he paints to understand the role of Veronica’s veil in the series.

Rouault disparaged the commercialization of modern life and its encouragement of what he saw as performative posturing or mask-wearing. He explains this revelation in a story about a time he happened upon a clown mending his costume.

The gypsy women stopped along the road, the emaciated old horse grazing on the thin grass, the old clown sitting on the corner of this wagon mending his bright, many-colored costume. The contrast between brilliant and scintillating things made to amuse us, and their infinitely sad life, if one looks at it objectively, struck me with great force. I have expanded all of this. I saw clearly that the ‘clown’ was myself, ourselves, almost all of us. This spangled costume is given to us by life. We are all of us clowns, more or less, we all wear a ‘spangled costume’ but if we are caught by surprise, the way I caught that old clown, oh then; who would dare to claim that he is not moved deeply by immeasurable pity? {Rouault Letter to Eduard Schuré 1905].

In this series and in his work more broadly, Rouault sees Christ in the sorrow of the clowns, the prostitutes, the poor and the downtrodden. His representations of Christ reflect their gestures and facial expressions. Rouault believed that the figures who hold their heads up as though they are above reproach or the need for Christ’s mercy are the ones who are in real danger. Like Dostoyevsky, he understood the danger of lying to ourselves.

“Above all, don't lie to yourself. The man who lies to himself and listens to his own lie comes to a point that he cannot distinguish the truth within him, or around him, and so loses all respect for himself and for others. And having no respect he ceases to love.”―Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

Rouault’s art is compassionate but not comfortable. He aims to confront his viewers and prompt self-reflection about the masks and pretenses we do and do not recognize we hold. He does this by holding up the face of Christ to us, interspersed with images of suffering and pride. Rouault presents Christ to us as the Suffering Servant from Isaiah, and in doing so he communicates solidarity with the suffering and poor, and judgment to the haughty or those unwilling to see the suffering they cause. Ultimately, he found himself in all of the figures he created, as should we.

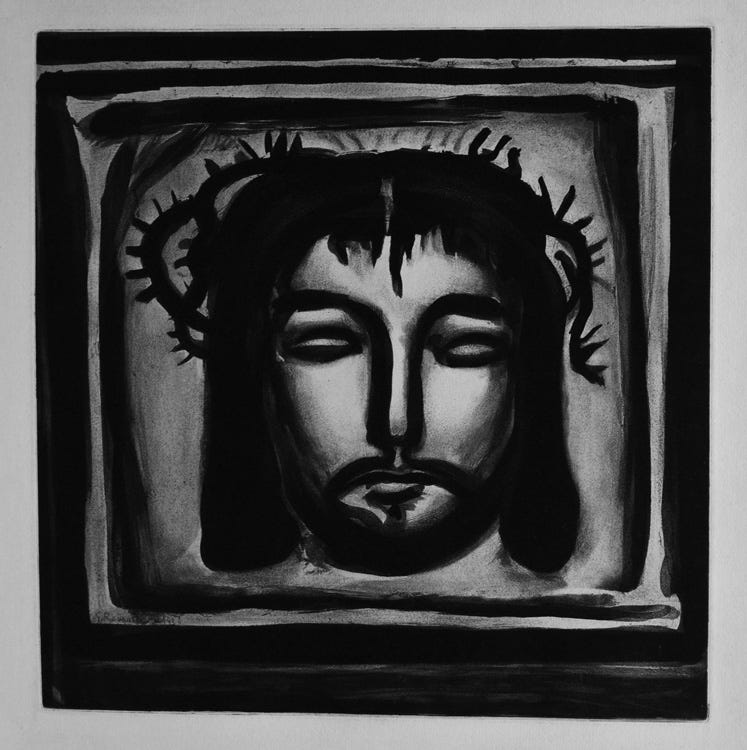

Plate 33 is the last in the first part of the Miserere and is entitled “And Veronica, with her tender linen, still walks the road.” The thick black lines of the veil’s outline and Christ’s nose are reminiscent of the lead of stained glass. Rouault substitutes the rigid lines of the lead with more flexible, expressive marks. The prevalence of the thick black paint in the outline of Christ’s face and his crown of thorns gives a heaviness to the print that communicates the depths of Christ’s suffering and agony. Just as light illuminates stained glass from behind, the image seems to glow from behind. The image has a bleakness, but it is not without hope. The light that shines through Christ’s cheeks hints at the transcendence of the resurrection. His eyes are closed and appear serene.

This plate reminds us that Christ sunk to this depth of suffering and horror. In the caption to this image, Rouault brings the image in conversation with the others and reminds us that just as “Veronica still walks the road,” Christ also continues to walk with us, uniting our suffering with his.

Like Veronica, we too should recognize Christ in the ordinary people around us and offer compassion. As Veronica recognized Christ and allowed him to wipe his face, Christ recognizes us and invites us to stand before him so he can wash away our masks and find in him the peace that the world cannot give. Rouault hoped that his art would be like Veronica’s veil for others in this way.

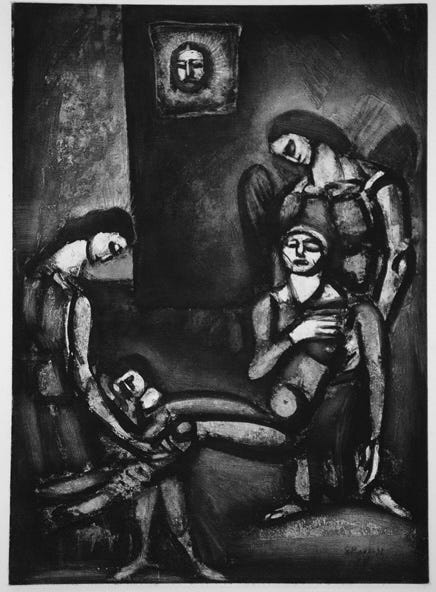

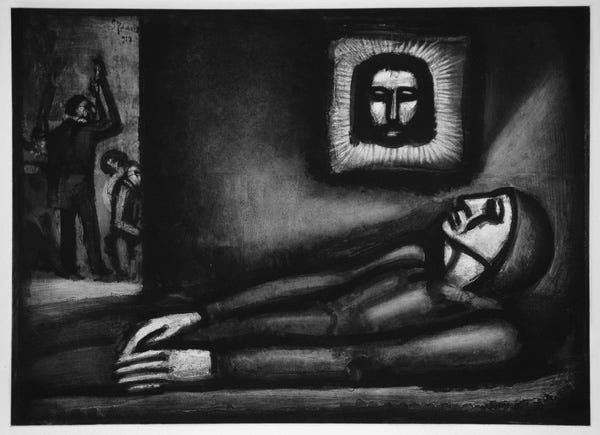

In plate 47, Christ looks down from the veil on a dead man with a consoling gaze. The scene is dismal and dark but for the light that shines brightly from the veil reminding us that Christ is still present in this man’s suffering and death. The caption, “Out of the depths I cry to you, oh Lord” is from Psalm 51, one of the Psalms that is recited for the dead at funerals. The body and face of the man seem to take on Christ’s features, reflecting Christ’s union with the suffering. The man, though presumably dead, seems to lift his body to Christ’s glorified face on the veil, pointing to the hope of life to come.

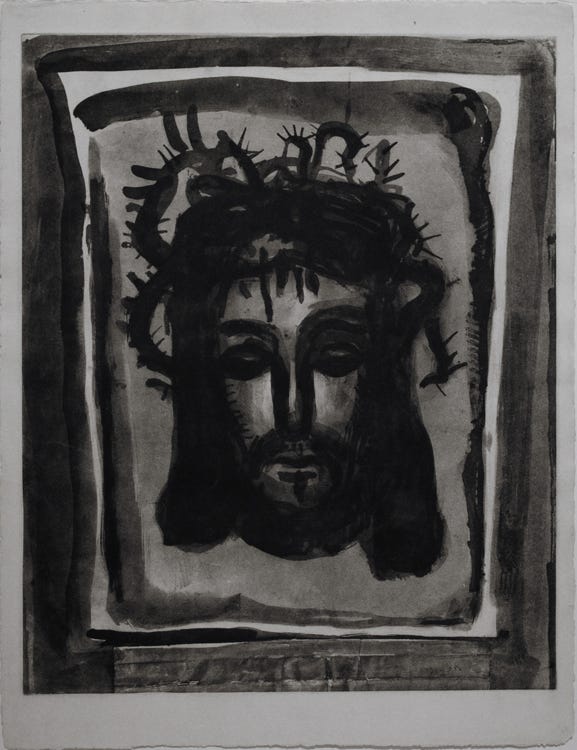

The last veil, which is perhaps the heaviest of all, presents a Christ almost consumed by a Medusa-like crown of thorns with the caption from Isaiah, “It is by his wounds we are healed.” Ending here, Rouault reminds us that we can’t go around suffering, only through it.

Rouault’s veils differ significantly from other paintings of Veronica’s veil. Whereas prior paintings of the veil present it in a way that creates the illusion that the painted veil is the real veil, Rouault’s veil has a “worked” quality to it that draws attention to the fact that it is not the actual veil.

Art historians have a hard time figuring out exactly what Rouault’s methods were because of how many times he reworked his paintings and etchings.

Rouault understood this as a gesture of humility, acknowledging that he was not capable of making a “true icon” in the way Christ was. He was not trying to give the illusion that his prints of the veil were the actual veil. Rather, he was trying to communicate the spiritual truth of the encounter and the way we can strive to imitate Veronica’s recognition and compassion.

Towards the end of his life, Rouault moved away from bleak portraits and painted serene, transfigured landscapes with bright, even luminous colors. Maritain believed these paintings showed a kind of spiritual maturity where Rouault felt peace and a deeper union with Christ.3 Although Rouault has the reputation for being a tortured soul, his family —namely his wife Marthe and their four children—remembered him primarily for his joy.

This hope is reflected in his painting of Veronica, which he painted in his seventies. One could mistake her look of joyful innocence for sentimentality if one wasn’t familiar with the rest of his work.

In Veronica, Rouault saw an example of someone who prevailed in hope and compassion when everything around her seemed darkest. Rouault reminds us that Christ can transform small, seemingly futile, acts of compassion into miracles that have eternal significance. “Charity never falleth away” (1 Corinthians 13:8).

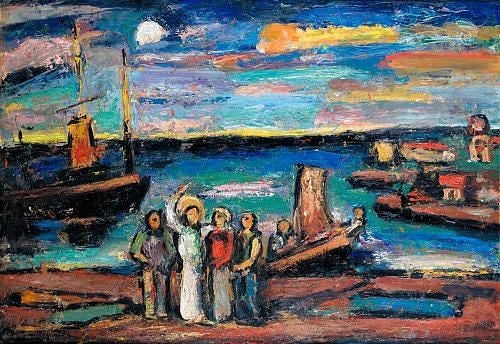

Christ and Fisherman, 1935-1937, Georges Rouault

This is an insight I got from Jacques Maritain’s excellent little book on Rouault, which is entitled Roualt. I read it on Scribd, but loved it so much I also bought a copy. https://www.scribd.com/document/604939166/GEORGES-ROUAULT

The series was not shown until 1948 due to a dispute Roualt had with his dealer, but the prints were largely completed between 1914-1927.

“To the extent to which his own spiritual experience became deeper, creative emotion was to take place also in deeper regions of his soul, farther from the noise of the external world; and at the same time the exigencies of the plastic expression developed a purer and freer urge toward harmonic expansion. As a result, Rou- ault's painting entered a sphere of growing light and clarity.” from Maritain’s Rouault