She is the ark of the covenant, The bush of vision, Gideon's fleece, That is moistened with the dew of the air, The sum of the old law, Solomon's temple, And the sublime throne Above the other thrones.

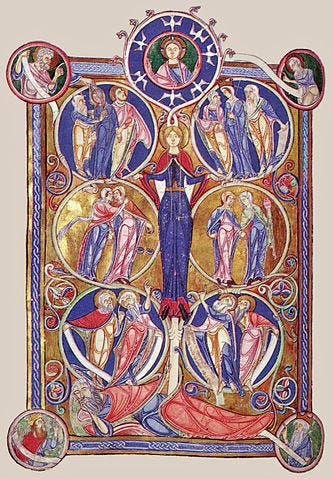

The Marian titles from the 12th century hymn above, may seem strange to us now, but they abound in medieval Marian hymns, breviaries, paintings and of course in the liturgy itself.1 Symbols of these titles, which are drawn from Old Testament imagery, are often brought together in Marian paintings and are incorporated in a more naturalistic way in the triptych above by the Gothic painter Nicolas Froment.

Of all the Marian doctrines, the Immaculate Conception, is perhaps the most notoriously controversial and difficult to conceptualize. Today, I am not going to expound upon the technicalities of the theological argument. Rather, I wish to explore the positive typological vision of Mary’s perpetual virginity, spotless purity, and her Divine Motherhood which was explained by the Church Fathers, preserved in the liturgy, and woven into the Christian tradition by the artists and poets.

The Flemish artist Nicolas Froment painted this magnificent triptych as an altarpiece for a Carmelite Church in Southern France. Commissioned by the French King Renee of Anjou, the painting brings together many of the Marian titles and symbols which were popular in French literature and song at the time. It is a profound Marian meditation which helps us to see and feel that Mary is as the Eastern Fathers said, Panagia, all holy. Every single detail of the painting is pregnant with symbolism which would have been easily understood by a medieval viewer. Below I will use Medieval hymns and antiphons to help bring these symbols to life for our 21st century eyes.

The Burning Bush

“In the bush which Moses saw unconsumed, we acknowledge thy admirable virginity preserved, intercede for us, O Mother of God.”—Antiphon for Christmas Eve vespers, tryptich inscription2

This beautiful and complex tryptich brings together two important stories from the Old and New Testaments—that of the burning bush and the Annunciation. Inspired by this antiphon from the Christmas Eve liturgy, the painter weaves these two events together giving us the perspective of eternal time and showing how one event finds its fulfillment in the other.

At the bottom of the painting a startled Moses, who is surrounded by a flock of sheep, holds his hands up in awe as he removes his shoes. From Moses, our eyes follow the winding stream up to the mountain from which a cosmic rose bush, with 12 trunks, springs forth.3 Mary sits atop the mystical flaming rose bush, presenting her son, the Christ. By painting Mary atop the burning bush, the artist brings to life the typological reading of the Moses story from Exodus which was put forth by numerous Church Fathers.

“The bush was burning, but it was not consumed, because it was a type of the holy Virgin Mary, who was filled with the fire of the Holy Spirit, but remained a virgin.”—Saint Ephraim (d. 373)

The angel in front of Moses in the painting recalls famous annunciation paintings and helps tie these two stories together. As the Angel Gabriel appeared to Mary as a herald of the Divine, announcing that she would become the mother of the Savior, God appeared to Moses in the burning bush announcing that Moses would lead God's people to the promised land. Both Mary and Moses are unique heralds for the coming of the Messiah. When the triptych is closed, this connection becomes explicit as the artist has painted a scene of the Annunciation on the front panels.

There the angel of the Lord appeared to him in flames of fire from within a bush. Moses saw that though the bush was on fire it did not burn up. So Moses thought, “I will go over and see this strange sight—why the bush does not burn up” (Exodus 3:2-3).

Mary’s experience is of course different from Moses’s, for she does not merely see God; she holds God within her womb and is the Godbearer. The same fire that burned in the bush in front of Moses burned inside the womb of the Virgin. Because of this, Saint Ephraim, as well as Gregory of Nyssa, John of Damascus and many other church fathers compare Mary’s perpetual virginity to the burning bush.

Gregory of Nyssa (d. 394) explains it this way in his book The Life of Moses:

What was prefigured at that time in the flame of the bush was openly manifested in the mystery of the Virgin, once an interval of time had passed. Just as on the mountain the bush burned but was not consumed, so also the Virgin gave birth to the light and was not corrupted. Nor should you consider the comparison to the bush to be embarrassing, for it prefigures the God-bearing body of the Virgin.4

So for the Fathers, the burning bush represents Mary’s perpetual virginity, but the fire is also a visible sign of her charity, of a heart inflamed by the love of God.

Both the burning bush and Mary’s divine motherhood present the mystery of this union between God and his creation. As Saint Gregory of Nyssa further explains:

Lest one think that the radiance did not come from a material substance, this light did not shine from some luminary among the stars but came from an earthly bush and surpassed the heavenly luminaries in brilliance.

In other words, God chose to dwell within his creation. That this image is used for the Christmas Eve liturgy is fitting as the burning bush prefigures the Incarnation.

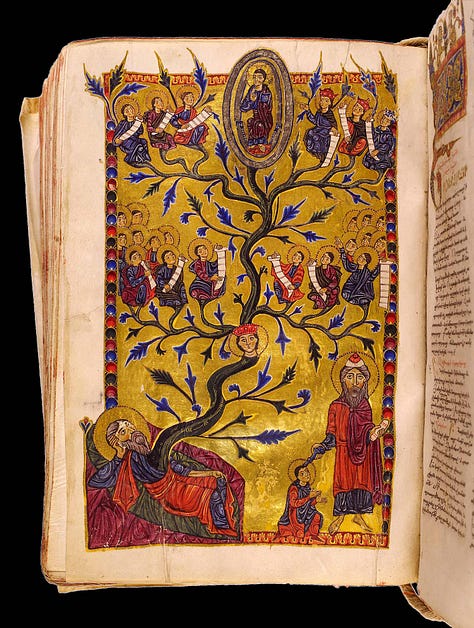

Tree of Jesse

I know a rose tree springing, Forth from an ancient root, As men of old we singing, From Jesse came the shoot That bore a blossom bright Amid the cold of winter, When half spent was the night.

This rose-tree, blossom laden, Where of Isaiah spake, Is Mary, spotless maiden Who mothered, for our sake, The little Child, newborn, By God's eternal counsel, On that first Christmas morn.—16th century hymn, popularly known as “Low How A Rose E’re Blooming”5

Although it is somewhat uncommon to see Mary positioned atop a burning bush in Western painting, it is not uncommon to see her atop a Jesse tree, as the final bloom from which the flower of the Christ child came or sometimes as the stem. The tree that Mary sits upon in this painting has multiple meanings. Froment uses the frame to bring attention to this symbol as he has painted Christ’s ancestors who would be featured in Jesse tree on the sides of the frame

These images illustrate the passage from Isaiah 11:1 as it is fulfilled in Christ, through Mary’s fiat: “There shall come forth a shoot from the stump of Jesse, and a branch shall grow out of his roots.”

In the Latin Vulgate Bible the word for branch is virga, which puns with virgin and no doubt influenced images of the Jesse tree. Many church fathers, such as Tertullian (d. 240) also understood Mary as the stem of the tree from which Christ came.

In what sense, really, is Christ the fruit of her womb? Is it not because he is himself the flower from the stem which came forth from the root of Jesse, while the root of Jesse is the house of David, and the stem from the root is Mary, descended from David, that the flower from the stem, the Son of Mary, who is called Jesus Christ, must himself also be the fruit?

Connected to this image are the many hymns and paintings that depict Mary using floral imagery, especially the rose, for the rose was the sweetest and most beautiful flower. The many flowers associated with Mary remind us of her humility, charity, purity, and hope. In Mary, we see a Paradise, a soul made fertile for the Lord and the flowering of virtue.6

Spotless Mirror

Hail, holy temple of God, you give an example of virtues, mirror of purity—12th Century hymn7

Another small but important symbolic detail is the mirror which reflects the image of Jesus, Mary, and the tree. The spotless mirror (Wisdom 7:26), another common medieval symbol for Mary, invites us to contemplate how perfectly the Blessed Mother reflected the virtue of her son. Notably, Froment puts the mirror in the hands of Jesus, reminding us that Mary is not vain like the goddess Venus, who is often painted holding the mirror.

This image of Mary, Jesus and the tree of life in the mirror compares to another significant detail in the emblem of the angel’s clasp, which features Adam and Eve standing in front of the tree of knowledge. The tree behind the angel reminds us that Mary and Jesus are the new Adam and Eve, and the tree is the cross. In this painting and others, Mary is also depicted as the tree that connects heaven and earth, the tree upon which the fruit of Divinity blooms.

Spring of life

As a life-giving fount, thou did conceive the Dew that is transcendent in essence, O Virgin Maid, and thou hast welled forth for our sakes the nectar of joy eternal, which does pour forth from your fount with the water that springs up unto everlasting life in unending and mighty streams; wherein, taking delight, we all cry out: Rejoice, O you Spring of life for all men—Apolytikion (Tone 3) based on 9th century hymn by John the Hymnographer 8

Finally the spring which flows forth from the rock symbolizes another prominent medieval Marian image, that of the fountain (Song of Songs 4:15), or the spring of living water. In a letter, St. Jerome (d. 419) refers to the Virgin using these words from the Prophet Joel:" a fountain shall come forth of the house of the Lord, and shall water the torrent of thorns" (Joel 3:18).9

The living Water is, of course, Mary’s son Jesus Christ. That the water flows from the rock, reminds us of when Moses struck the rock "and [God] brought water out of the rock, and caused waters to flow down as rivers" (Psalm 78:16; also Exodus 17) and also the Gospel of John: "If any man thirst, let him come unto me, and drink. He that believes in me, according to the Scriptures, out of his belly shall flow rivers of living water." (John 7:38)

Froment, perhaps drawing on Saint Jerome or various popular hymns presents Mary as the source of this living water, for it is fitting that pure water come from a pure source and it is from Mary that Christ receives his humanity.

Moses’s flock of sheep, who represent the Christian flock, drink from the life-giving waters. Still, within the flock, a black sheep with beady red eyes lurks amidst the sheep reminding us that sin lurks among us.

There are more symbols—the unicorn in the corner of the frame, the city behind Mary, the towers, the rising sun—but I will leave our exploration here for now so we can meditate on the most prominent images. By exploring the richness of the biblical images, we can come to a more full appreciation of Mary which helps us to see a positive vision of her purity.

Finally, the side panels feature the donor and his wife along with their respective patron saints. Mary Magdalen, Anthony and Maurice surround King Renée while Saints Nicholas, Catherine, and John the Baptist stand behind his wife Jean De Laval.

This triptych was meant as an altarpiece and the donors posture as well as Moses’s remind us what our own posture should be before the Lord of Hosts who descends from Heaven to meet us in the liturgy. As Gregory of Nyssa explains:

That light teaches us what we must do to stand within the rays of the true light: Sandaled feet cannot ascend that height where the light of truth is seen, but the dead and earthly covering of skins, which was placed around our nature at the beginning when we were found naked because of disobedience to the divine will, must be removed from the feet of the soul.10

https://mdpi-res.com/d_attachment/religions/religions-15-01446/article_deploy/religions-15-01446.pdf?version=1732719704#page40

Haec est arca foederis, Rubus visionis, Rore madens aetheris, Vellus Gedeonis, Legis summa veteris, Templum Salomonis,Et thronus prae ceteris, Sublimatus thronis.

These 12 trunks represent the 12 tribes of Israel, which are fulfilled in the Church, of whom Mary is an image.

http://www.newhumanityinstitute.org/pdf-articles/Gregory-of-Nyssa-The-Life-of-Moses.pdf

This hymn is more commonly known in English as “Lo How a Rose E’re Blooming.” The most popular English translation is by Henry Baker, who removed and changed the Marian parts of the original hymn.

https://www.hymnsandcarolsofchristmas.com/Hymns_and_Carols/Notes_On_Carols/lo_how_a_rose_eer_blooming.htm

Listen to the original German hymn here:

https://mdpi-res.com/d_attachment/religions/religions-15-01446/article_deploy/religions-15-01446.pdf?version=1732719704#page40

Used in the Bright Friday liturgy of varios Orothodox and Eastern rite liturgies. https://orthodoxpraxis.org/2020/04/

https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf206.v.XLVIII.html

http://www.newhumanityinstitute.org/pdf-articles/Gregory-of-Nyssa-The-Life-of-Moses.pdf

Phenomenal work on this, happy feast day!

😌 ❤️ 🏔️ 🌐 The Uncut Mountain(Daniel), the Eastern Gate [Ezekiel], the Burning Bush Unconsummed, the Root of Jesse, Aaron's Rod that budded, behold Zion.

.....grace 🔥and peace ⛲to you sister! This post is very helpful for all who love and venerate our Lady and Queen. 🎶 ⛪ ☦️ ⏳More Honorable than the Cherubim and beyond compare more Glorious than the Seraphim, thou who without corruption Bearest God the Word and are Truly Theotokos, thee do we magnify. Onward to Bethlehem! ✨ 🌴 🐪 👑