Tucked away amid the desert mountains of Sinai, is St. Catherine’s Monastery, the oldest continuously inhabited monastery in the world. In the heart of this Eastern Orthodox monastery, the basilica houses the oldest known depiction of Christ’s Transfiguration.

Responding to requests from monks in the area, St. Helena, mother of Constantine, built the first chapel around the relic of the burning bush close to 330 AD. Later, Emperor Justinian built the basilica and fortress in the sixth century, and shortly thereafter the mosaic was erected. For nearly 1500 years, the mosaic has been a central part of the liturgical life of the monastery. Amazingly, the Byzantine mosaic has survived earthquakes, floods, wind storms, Sacaren raiders, Arab conquests, and bouts of iconoclasm.

Fifty years ago the mosaic was in almost total disrepair after centuries of earthquakes and water damage. Today it shines luminously after years of conservation work, which was finally completed in 2016.1

It is especially fitting that the Transfiguration should take pride of place in the basilica on Mount Sinai—the mountain where God appeared to Moses and Elijah. Church Fathers understood the Transfiguration to fulfill these Old Testament theophanies2. While God appeared to Moses in a burning bush and to Elijah in the “still, small voice” outside the cave at Mount Horeb, he revealed himself to the apostles in the Transfiguration face to face, revealing his glorified humanity.

Perhaps it is the seventh-century monk from this monastery, Saint Anastasios of Sinai (630-700), who best summarized what the Transfiguration means for us:

Jesus goes before us to show us the way, both up the mountain and into heaven, and - I speak boldly - it is for us now to follow him with all speed, yearning for the heavenly vision that will give us a share in his radiance, renew our spiritual nature and transform us into his own likeness, making us forever sharers in his Godhead and raising us to heights as yet undreamed of.3

Upon entering the church, the lintel beam above the entrance to the narthex of the basilica reads in Greek: 'And the Lord spoke to Moses in this place saying, I am the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob. I am that I am.' This inscription from Exodus makes explicit the connection between the holy ground Moses walked on in his encounter at the burning bush and the sacred ground of this Church where the Divine Liturgy takes place.

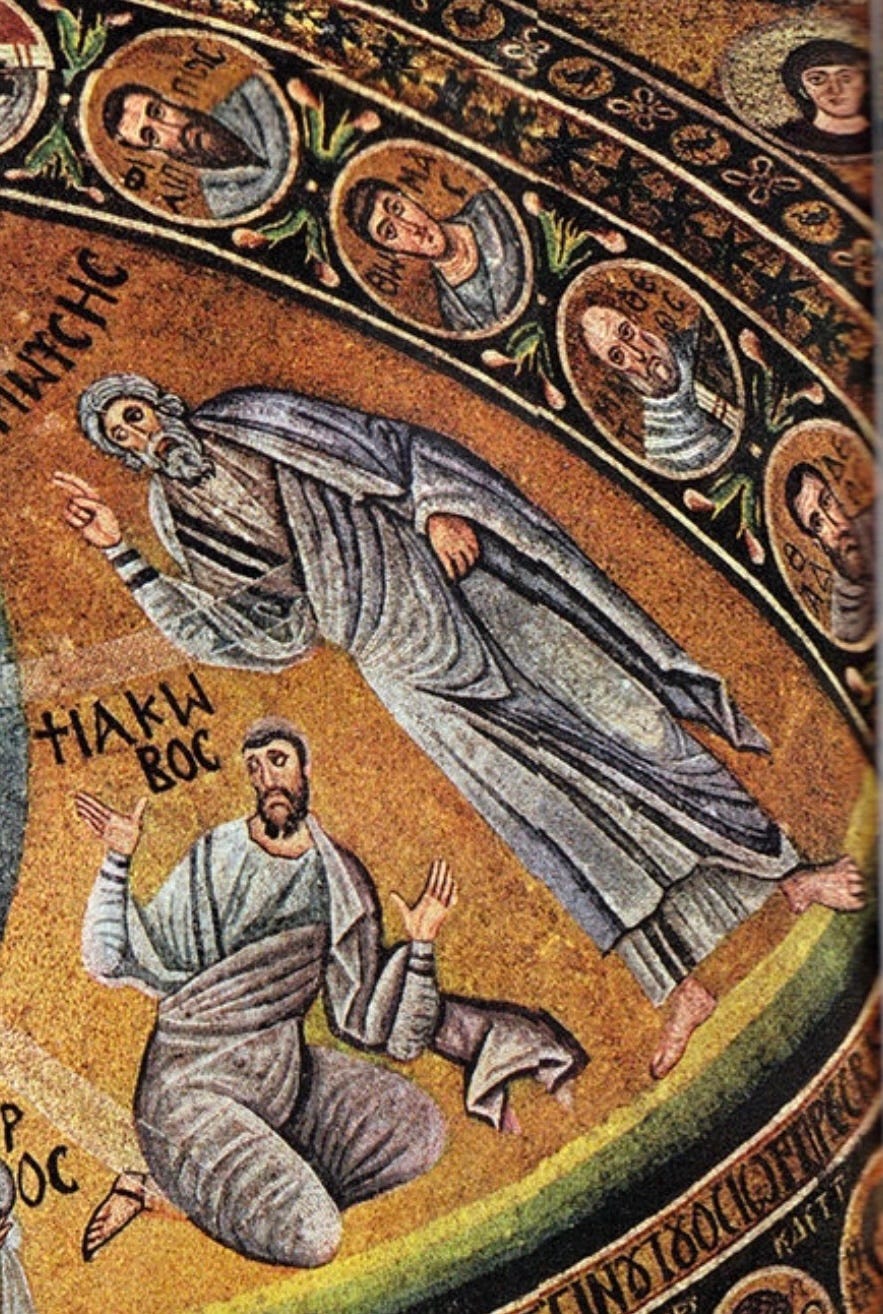

The Transfiguration is depicted on a conch apse, which is shaped and gilded to symbolize the cosmos. This vision of a heavenly cosmos points to the end of the Transfiguration, which is transfigured creation.

An oval mandorla that gets increasingly darker blue towards the center circles Christ, signifying his glorified humanity. Jesus wears “dazzling white” robes that resemble both what the High Priest wore when entering the Holy of Holies and also the garb of a Roman Emperor. This reveals Christ’s identity as both King and High Priest, while the lamb above the apse points to his sacrifice and his identity as the Lamb of God.

During the Transfiguration, Jesus gave the apostles a glimpse of his glorified humanity, foreshadowing the Resurrection. In a time when the Church was fraught with Christological heresies that had not yet been settled, this mosaic made a clear statement about Christ's nature as fully God and fully man.

From the center of the mosaic, Jesus looks directly out at the congregation, holding up three fingers, which points to the nature of the Trinity—three persons in one God. Eight rays of light emanate from the mandorla, symbolizing the resurrection and the Second Coming, which are understood to occur on “the eighth day.” 4 The light of these rays shines on Moses, Elijah, and the apostles, pointing to their destiny to share in Christ’s Resurrected Glory, as well as ours.

As Saint Macarius (400 ) put it: “the glory that was within Christ was outspread upon His body and shone; and in like manner in the saints, the power of Christ within them shall in that day be poured outwardly upon their bodies” 5

On either side of Christ, James and John kneel and crane their necks to see Jesus while Peter wakes from sleep. Ambrose of Milan (339-97) relates that while the apostles were awake, "they saw his majesty, for no one can see the glory of Christ unless he stays awake.6” Thus, to see this heavenly vision, we must wake from sloth and spiritual slumber and prepare to climb the mountain to see Christ. As pilgrims to this monastery would understand, this is no easy task.

That the mosaic itself does not include a mountain, as other images of the Transfiguration do, points to the fact that the monks and pilgrims who look at the mosaic already stood on a holy mountain. Having completed this arduous climb, the monks and pilgrims would be eminently prepared to receive the heavenly vision.

On the far sides of the apse, Elijah and Moses stand upright, gazing directly at Jesus. They remind us that Jesus fulfills the Law (Moses) and the Prophets (Elijah). Elijah, the exemplar ascetic, wears a monk's belt around his waist. He holds up three fingers, imitating Christ, while Moses holds up two, attesting to Christ’s nature as fully human and fully divine.

“A great cloud of witnesses” surrounds the central apse in circular medallions, presenting to us those heavenly saints who share in Christ’s heavenly splendor. The apostles line the upper boundary of the apse, and prophets from the Old Testament line the bottom. Above the apse, two angels offer orbs to the lamb. Medallions with Mary and John the Baptist are on either side of the angels.

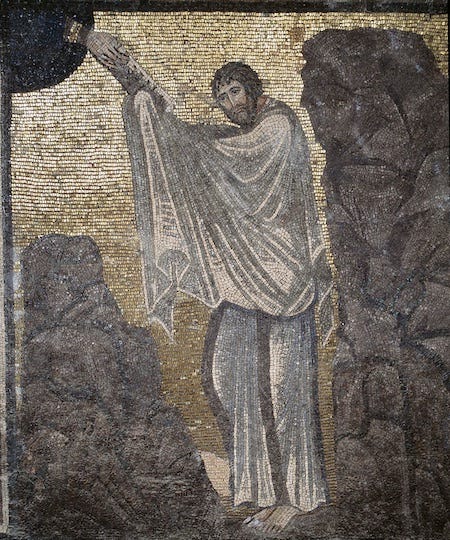

Two scenes from the life of Moses feature above the apse. These mosaics represent a paradigm of the spiritual journey or mountain for the monks and pilgrims who visit the church7. The upper left mosaic depicts Moses as a younger man loosening his sandals before God in the burning bush, which is located directly behind the basilica. Here on Mount Horeb, Moses accepted the call from God to lead the Israelites. Thus began his ascent up the mountain of spiritual life. After this theophony, he accepted his vocation as leader of the Israelites.

The upper right mosaic depicts an older Moses in the cleft of the rock on Sinai receiving the Law from God. In this second theophany to Moses, God appeared further up the mountain in a dark cloud. When Moses came down with the stone tablets of the Law, his face shone with the radiance from his encounter with God. Still, Moses did not receive the full vision of God until the Transfiguration, when he saw Christ, the embodiment of the Law, face to face.

Moses does not look directly at God in either of these depictions. On the left panel, Moses looks above the bush, and on the right panel, he looks out at the congregation. Only the older Moses, featured in the central apse, looks directly at God. Perhaps Moses looks out at the congregation in the upper right panel to remind congregants of the Heavenly Vision they receive in the Divine Liturgy.

Art historian Jas Elsner makes the point,

Ultimately, the cardinal image on which the whole scheme at Sinai is pivoted is the lamb adored on the triumphal arch. For it is to Christ, "the lamb of God which taketh away the sins of the world" (John 1.19), that the theophanies ladder of Moses and Elijah ascends. It is in the lamb as eucharist that the congregation is saved and partakes of Christ. The lamb as the Body which the worshiper eats is Christ.8

But, as the lives of Moses and the apostles remind us, this glimpse of Heaven should not end our ascent but further spur us on in our vocations and in our own spiritual climb.

As Gregory of Nyssa (300-386) said in his book on the life of Moses, "He [God] would not have shown himself to his servant if the sight were such as to bring the desire of the beholder to an end, since the true sight of God consists in this, that one who looks up to God never ceases in that desire" 9

Today, the mosaic is partly hidden by the cross on top of the 16th-century iconostasis. Although Jas Elsner relates that the monks wish to take it down because the monetary has not produced any saints since it was erected.

A theophany is understood to be an appearance of God.

https://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2017/08/on-transfiguration-of-christ-st.html?m=1

Eight day

St. Macarius the Great, Homily XV, excerpted from Fifty Spiritual Homilies of St. Macarius the Egyptian, Translated by Arthur James Mason, edition 2019 by CrossReach Publications, Waterford, Ireland

Jas Elsner. *Art and the Roman Viewer: the transformation of art from the Pagan world to Christianity* (Cambridge University Press 1995), 121

Ambrose, In Lucam 7.17 (PL. 15.1791)

This idea is discussed in Jas Elsner’s essay: and “Viewing and the Sacred,” in Art and the Roman Viewer: The Transformation of Art from the Pagan World to Christianity (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 88-124

Elsner, 120

Gregory of Nyssa. The Life of Moses. Translation, Introduction and notes by Abraham J. Malherbe and Everett Ferguson. (NY: Paulist, 1978). 115

I feel like I was there!

Catching up a bit after my travels. How wonderful that this was restored so that monks and pilgrims can continue to contemplate it.