When Thou hadst fulfilled for us Thy dispensation, and united the things in earth with the things in Heaven, Thou, O Christ our God, didst ascend into glory, in no wise being parted from those that love Thee, but Thou didst remain with them inseparably and proclaim to them: I am with you no one is against you.— Kontakion (Byzantine hymn) for the Ascension, by Roman the Melodist, 6th Century

Saint Gregory of Nyssa (d. 394) calls the Ascension “the consummation and fulfillment of all other feasts and the happy conclusion of the earthly sojourn of Jesus Christ.”1 The Ascension is one of the great Christological feasts; however, it is now largely ignored or misunderstood.

Pope Saint Leo the Great (d. 461) very clearly explains why the feast is so important in a homily:

Since then Christ’s Ascension is our uplifting, and the hope of the body is raised, wither the glory of the Head has gone before, let us exult, dearly beloved, with worthy joy and delight in the loyal paying of thanks. For today not only are we confirmed as possessors of paradise, but have also in Christ penetrated the heights of heaven.2

It is easy to miss the significance of the feast of the Ascension and to see it merely as a commemoration of Christ’s separation from this earth.3 There are many reasons for this, but I think some part of the misunderstanding may be due to the way realistic paintings of the Ascension, which have dominated depictions of the event for at least 500 years, woefully misrepresent the great theological mystery.4 These paintings (below) depict the Ascension merely as a human event, downplaying elements which point to Christ’s divinity and mystical glory. In these images, Christ does not ascend into heaven but merely into the sky. Angels are also notably absent.

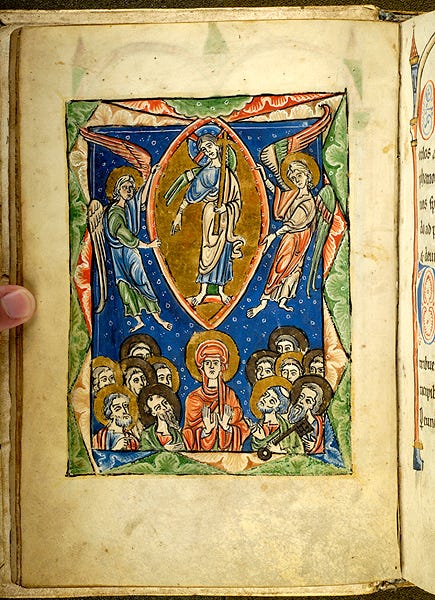

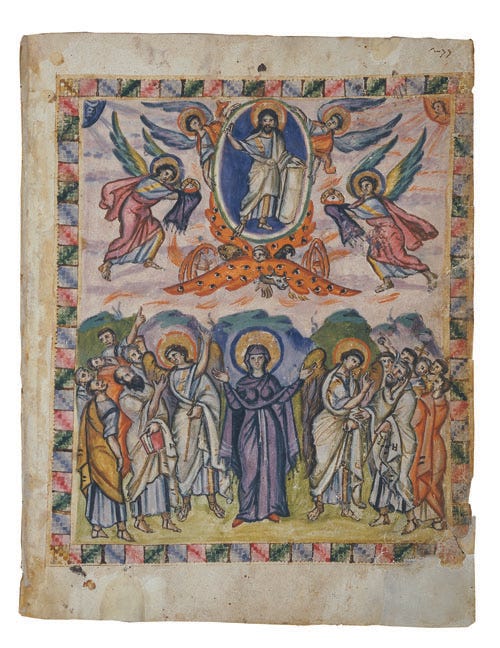

Contemplating the prototype of the Ascension (below), which dominated Eastern and Western art for over a thousand years, can provide a corrective and help us to see the event as the Church Fathers did.5

These early images were popular in the fifth and sixth centuries, as evidenced by pilgrims’ ampulla we have from the time, which were used to gather oil from holy sites. They were also often featured prominently on the domes of churches.6

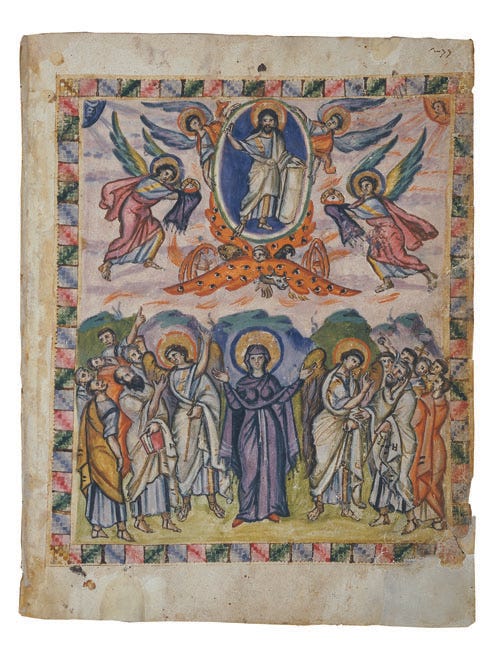

One of my favorite early images is the illumination from the ancient sixth century Syriac manuscript, which was illustrated by a monk named Rabbula (below). We do not know much about him, other than that he served at the monastery of John of Zagba.7

The image illustrated here does not merely depict Christ flying off into the sky; rather, it illuminates his glorified humanity and his eternal reign in heaven with the Church. The artist incorporates elements from Ezekiel’s “vision of the likeness of the glory of the Lord” (Ezekiel 1:28).

In the illumination, Christ, who is dressed as a Roman Emperor, blesses the apostles (Luke 24:50) as he ascends in a chariot surrounded by the four tetramorphs from Ezekiel (1:16-28) and Revelation (4:6-8). Ezekiel describes in detail “the likeness of four living creatures” (Ezekiel 1:9).

He writes: “Their wings were joined one to another... As for the likeness of their faces, they four had the face of a man, and the face of a lion, on the right side: and they four had the face of an ox on the left side; they four also had the face of an eagle (1:9-11).

Above the creatures Ezekiel sees "the likeness of a throne” with “the appearance of a man above upon it" (1:28). The man is attended by four Seraphim who move on four wheels that "sparkled like topaz" (1:15-16).

The images from Ezekiel’s vision as well as the oval mandorla which surrounds Christ point to his majesty and divinity. The blue mandorla is also symbolic of the union of Heaven and earth, a realization of Christ’s priestly mission. These same elements are also present in images of the Transfiguration, the Last Judgement, and Christ in Majesty—all events/images which reveal Christ’s divine glory.

The mandorla is also an allusion to the divine cloud which appears in the biblical account. In a sermon Benedict XVI reminded us of the significance of this cloud:

The presence of the cloud that "took him out of their sight" (v. 9), recalls a very ancient image of Old Testament theology and integrates the account of the Ascension into the history of God with Israel, from the cloud of Sinai and above the tent of the Covenant in the desert, to the luminous cloud on the mountain of the Transfiguration.

To present the Lord wrapped in clouds calls to mind once and for all the same mystery expressed in the symbolism of the phrase, "seated at the right hand of God". In Christ ascended into Heaven, the human being has entered into intimacy with God in a new and unheard-of way; man henceforth finds room in God for ever.8

This intimacy Benedict XVI speaks of is also expressed through the Mount of Olives in the background, which recalls other biblical events where God comes to meet his people. The mountain is the biblical place where heaven and earth meet. John Crysostom (d. 407) makes clear that this is what happens in the Ascension:

Through the mystery of the Ascension we, who seemed unworthy of God’s earth, are taken up into Heaven. . . . Our very nature, against which Cherubim guarded the gates of Paradise, is enthroned today high above all Cherubim.9

Thus, the icon is one of God making a place for humanity in heaven. Although only Christ ascends, the whole image seems to move upward, foreshadowing the future glory of the Church and the Saints. The feet of the apostles even seem to lift off the ground. Mary lifts her hands upwards while the apostles point. Some even seem to stretch up to heaven.

It is through the Church, which is pictured in the lower half of the image, that we are brought to glory and salvation with Christ. In the Ascension, Christ returns to reign with his Father and opens the gates of Heaven for us to follow him.

In these images, Mary, the personification of the Church, stands firm beneath Christ, her hands open in prayer. Here, she represents both the throne and body of Christ, which extends out to the apostles around her.10

The apostles, including Paul who holds the book on the left and Peter who holds the keys on the right, surround the Theotokos pointing up, wondering, questioning, exclaiming. Although God has not yet sent the Holy Spirit to enlighten them, he has sent angels to console them: “Two men in white robes stood by them. They said, 'Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking up towards heaven? This Jesus, who has been taken up from you into heaven, will come in the same way as you saw him go into heaven” (Acts 1:9-11)!

Joined together, the two halves of the image help us to see Christ as the head of the Church. Although it is an image of separation in some ways, it is also an image of the unity of the Church. Christ is present with his Church even as he reigns in heaven. Before ascending, Christ told his apostles “Behold I am with you all days, even to the consummation of the world” (Matthew 28:10). With confidence that Christ is alive and glorified in heaven, they return to Jerusalem not with tears but “with great joy” (Luke 24:52).

In this image, angels also carry Christ’s purple garment up to the father, the same one he is often pictured wearing in early scenes of the crucifixion. The angels are not only messengers here, but an expression of Christ’s glory and majesty.

The sun and moon in the corners of the image remind us that his reign extends throughout the cosmos. Here, heaven is not just an image of the sky. It is the revelation of God’s glory and a foreshadowing of the Last Judgement.

The image is framed with an ecstatic border, and the heavenly or upper part of the image is illuminated with an explosion of color, filled with the thrones and dominions, along with their wheels and strange eyes, as are described in Revelation.

In the Rabbula image of the Ascension, we see that the gates of heaven are open for humanity, but also that heaven is something much stranger and more glorious than we usually imagine. I am reminded again of what Pope Benedict XVI had to say about heaven on the occasion of this great feast:

Heaven: this word does not indicate a place above the stars but something far more daring and sublime. it indicates Christ himself, the divine Person who welcomes humanity fully and for ever, the One in whom God and man are inseparably united for ever. Man's being in God, this is Heaven. And we draw close to Heaven, indeed, we enter Heaven to the extent that we draw close to Jesus and enter into communion with him. For this reason today's Solemnity of the Ascension invites us to be in profound communion with the dead and Risen Jesus, invisibly present in the life of each one of us.11

In Ascens. Christi; PG, 46, 689

So why did Gregory call the Ascension a “consummation?” In his article on the feast, Fr. Herman Majkrzak explains how Christ completes his priestly work through the Ascension, following the pattern of sacrifice set out in the Old Testament.

Sacrificed outside the city walls of Jerusalem, his priestly work was not completed until he entered "into heaven itself, now to appear in the presence of God on our behalf" (Heb. 9:24), "taking not the blood of goats and calves but his own blood, thus securing an eternal redemption" (ibid.v. 12).

See Fr. Herman Majkrzak’s excellent essay on the Ascenscion:

In some dioceses the feast remains on Thursday. In others it is moved to Sunday. This has certainly created some confusion about whether the Thursday feast is a holy day of obligation or not.

There are also medieval images which show only Christ’s feet. This is supposed to symbolize how Christ ascends, but his body also stays with the Church through the Eucharist. These images usually include angels and some kind of mandorla which is not wholly visible.

I am not saying that there have not been any good images of the Ascension for 500 years, or that only early images of the event or valid.

See also: https://www.catholicculture.org/culture/liturgicalyear/activities/view.cfm?id=1309

Ouspensky, Leonid, and Vladimir Lossky. The Meaning of Icons. Translated by G. E. H. Palmer and E. Kadloubovsky. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1982. First published 1952 by Urs Graf Verlag. P. 194-199

https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=53846

https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/homilies/2009/documents/hf_ben-xvi_hom_20090524_cassino.html

Hom. in Ascens., 2; PG, 50, 444

Ouspensky, Leonid, and Vladimir Lossky. The Meaning of Icons. Translated by G. E. H. Palmer and E. Kadloubovsky. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1982. First published 1952 by Urs Graf Verlag.; p. 194-199

https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/homilies/2009/documents/hf_ben-xvi_hom_20090524_cassino.html

So many treasures in this post. I love a good Byzantine hymn. Every line sledgehammers you with theology. Also that final excerpt from Benedict's sermon is so beautiful. I need to read more of him.

These early images you share bespeak a holy imagination, respect, profundity, mystery, learning, restraint. But the 17thc naked flying Jesus? Horrors! I can’t look at them. Today everyone’s favorite image of Our Divine Lord and Savior is a slope-shouldered hippie-guy, totally sentimentalized.

Sorry to gripe.

Thank you for writing about true beauty.