The Stations of the Cross and the Seven Falls in Medieval Germany

On the oldest, fully preserved Way of the Cross in Europe

During Passiontide, the fortnight before Easter, the Church turns her attention towards Christ’s Passion. Veils often shroud statues and images during this time, mortifying our sight and preparing us to see with eyes of faith. The Stations of the Cross; however, traditionally remain unveiled. As such, they call out for our attention.

In the introduction to his 15th century book The Spiritual Pilgrimage, Carmelite prior Jan Pascha explains the spiritual purpose of this devotion, which he helped to popularize:

Let us behold therefore what care and pains our loving LORD hath taken of our salvation, let us learn to travaille courageously and like devout and holy pilgrims to follow His steps, who hath left us an example of His blessed life and passion, and ruminate in our hearts every day apart, some general point thereof, and after well to practise the same in ourselves, for such ought to be the end of our spiritual exercise, by which means we may attain to the happy end that we desire.1

Today, we will explore the oldest versions of the Stations still standing, sandstone sculptures carved in the late Medieval period. From Passion plays to spiritual booklets, devotions to Christ’s Passion abound in this period. One such devotion was the Seven Falls of Christ, an early meditation on the Way of the Cross. Before the Stations were set at fourteen in the 18th century, the Seven Falls was a popular devotion, especially in Germany.2 Depictions of the Falls feature scenes from the Via Crucis in which Christ has fallen underneath the weight of the Cross. The Falls were also based on Proverbs 24:16, “For the just one will fall seven times, and he shall rise again. But the impious will fall into evil.”

Adam Krafft’s Stations are among the oldest surviving in Europe and based on the Seven Falls. Upon returning from a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, a German knight by the name of Heinrich Marschalk von Raueneck commissioned Krafft, a renowned Nuremberg sculptor, to carve stations around the town, transforming Nuremberg into a little Jerusalem.3 Krafft’s shrines served as a model for many others throughout Germany, including the Bamberg stations, which we will turn to shortly.

Like many of the early Stations, the shrines were built into the architecture of the city, starting at the gate of the town and ending at St John’s cemetery. Walking through the Stations or “stopping places” of Christ’s Passion functioned as a mini pilgrimage for those who could not travel to the Holy Land.

The carvings themselves seem to spill out from their shrine-like frames into the street. On a Friday night in Lent, illuminated by flickering torchlight, I imagine the overlapping figures would seem to move, even jump out at you a little. As Nuremberg pilgrims walked in the steps of Christ, chanting psalms, reciting prayers, and stopping to kneel at each station, these carvings assisted their meditation, bringing Christ’s Passion to life, challenging, haunting, and consoling pilgrims.

Processions of this sort were common not just in Germany, but all over Europe, especially later in the Baroque era (1600-1750). In Italy, confraternities would bring their own Crosses and paintings of the Stations to processions, and children would dress as angels. One chronicler wrote of a Stations procession in Milan, “It was as if the whole City was ... converted into one single and vast temple. Every night one heard a multitude of infinite voices praising God throughout the city and every Friday one saw devout men processing through the streets singing psalms and hymns that moved the soul of every good Catholic to devotion.” And another said, “Milan might at this time have not been unfitly compared to ... an image of the heavenly Jerusalem, filled with the praises of the angelic hosts."4

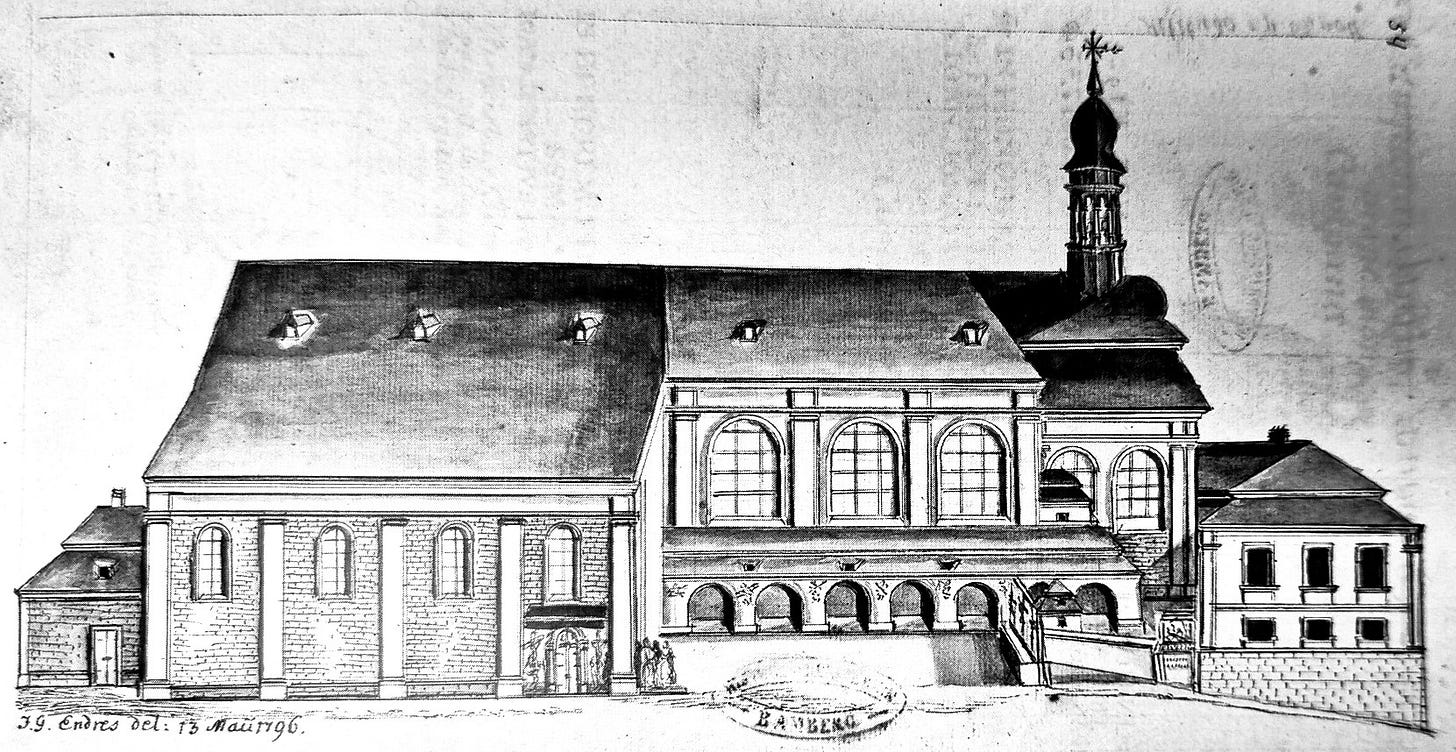

Heinrich, the knight, also commissioned similar Stations to be set up in his home town of Bamberg, an ancient Catholic town, home to the Holy Roman Emperor Saint Henry II, Saint Otto, and other saints. While the Nuremberg Stations have suffered harsh weathering over the years, and are preserved in a museum today, the Bamberg Stations are in remarkable condition after numerous restorations and still stand in their original places. They begin at Saint Elizabeth’s church in Bamberg, which was originally located next to the city gates. This location symbolically represents the Lion’s gate in Jerusalem, where the Way of the Cross began.

The Stations end on Michaelsberg hill at Saint Getreu church (Church of the Faithful), which is intended to mimic the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Originally, the Crucifix would have looked over the cemetery, but it is now located within the church, as is the Entombment.

While in the Holy Land, Henrich carefully measured the steps between each stop on the Via Crucis. The distance between the Stations is carefully marked in steps from “Pilate’s house” to resemble the distances between stops on the Jerusalem pilgrimage.

In the first Station, Christ picks up his Cross as Pilate and his family looks on from the safety of their house. The jeering faces of his tormentors contrast with Christ’s peaceful countenance. Although, they have put him on a leash like an animal, it is they who have become animals. The Stations read from right to left, making the scene all the more jarring to look at. The inscription reads: “Here, Christ is led out by Pilate, carrying his cross.”5

In the next Station, Christ meets his mother who collapses upon seeing Jesus. Here, Mary’s suffering is shown to be bound up with her son’s. Meanwhile the tormentors energetically proceed with torturing him, even seeming to jump at Christ. Christ’s head marks the center of the diagonals. The inscription reads: “Here Christ meets his dear, worthy mother, who is overcome by great heartache. 200 steps from Pilate's house.”

In the third station, Simone of Cyrene is selected to help Jesus carry his cross. On the right, the tormentors beat a small man, probably Simon. The executioners on the left point forward, with helpless expressions on their faces. The inscription reads: “Here Simon was forced to help Christ carry his cross. 295 steps from Pilate’s house.”

In the fourth station, the women come to console Christ. They stand tall in a visually ordered column, contrasting with the cacophonous movements of the rest of the onlookers. Their drapery billows downwards as do their tears. Christ looks back towards the women in mercy while the soldiers seem to pull him forward. The inscription reads: “Here Christ said, ‘Daughters of Jerusalem, do not weep for me, but for yourselves and your children.’ 380 steps from Pilate’s house.”

The fifth Station is also familiar to anyone who has prayed the stations before. Here Veronica stops to console Christ, offering him her veil. An imprint of his face is left on the veil, but the soldiers do not seem to notice. They are looking in all different directions. The inscription reads: “Here Christ has pressed his holy face into the cloth of Lady Veronica. 500 steps from Pilate’s house.”

In the last Station outside of Saint Gertreu, Christ lies prone on the ground, beneath the weight of the cross. The soldiers seem to pull him every which way. One on the right tugs at his hair. Another boasts a sadistic grin as he pulls the rope around Jesus’s body. The three soldiers on the left try to pull him upright. The inscription reads: “Here Christ, with great power, descends to earth beneath the cross. 1,100 steps from Pilate’s house.”

The Crucifixion scene was originally made to look over the church cemetery, but was brought inside the church in the 19th century. In it, Christ majestically towers over the two criminals crucified beside him. His countenance is serene, and his gold crown, which would have shone especially bright in the sun outside, points to his eternal glory. The good thief gazes up at Christ as the other looks away. Mary and John stand beneath the Cross. In the relief below the crosses, Jesus lays in the lap of his mother (Pieta motif.) Four other women and John surround his body in mourning.

In life size sculptures nearby, Christ is put into the tomb and is surrounded by Joseph of Arimathea (right) and Nicodemus (left) as well as Mary, John, and other women.

As we enter Passiontide, these sacred statues lend our minds moving images of his sacred Passion. The meticulous artistic detail and even geographical detail of the Bamberg Stations grant those stations in particular a special power. The recounting of the number of steps taken during Christ’s Passion serves two purposes. First, it makes Jerusalem feel more present even in the far-flung Gentile nations of Europe. Second, it reminds us that we are called to walk our own passion in imitation of Christ in our day-to-day lives, dying to self, and living in the freedom of his Resurrection. Although we may not be able to visit Bamberg today, we can still walk the Stations at our local churches.

Some of my favorite Stations of the Cross meditations:

Saint John Henry Newman:

Pope Benedict XVI:

Herbert Thurston S.J., “Stations of the Cross,” viij

For a more detailed look at the history of the Stations of the Cross see Deacon Tom McDonald’s recent post:

In another account, Martin Ketzel commissioned them. There isn't much evidence either way. See:

Silver, Larry. 2023. "Adam Kraft’s Moving Sandstones" Arts 12, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12010009

Pamela Stewart, “Staging the Passion in the Ritual City,” p. 217-255

https://media.bamberg.info/timm_docs/prospekte/flyer_kreuzweg.pdf

This was a wonderful post. Thank you! You reminded me of a magical trip to Nurnberg many years ago. The place, although bombed heavily during WW II, was brought back to its medieval character. I was in awe and roamed around, immersed in what it would have been like in those totally, earnestly Catholic days. St Lorenz church was the first medieval church I had entered with very high vaults. I was forced to look upwards, just like any medieval penitent, and felt Gods presence. It was quite an experience. Everywhere you look, inside and outside buildings in the old town you are on a medieval pilgrimage. I am so happy to be reminded of this blessing.

This was an enlightening article about the Bamberg stations. I was unaware of this devotion. And I love the photos.

Thanks.