Some art from the first few centuries of Christianity survives. The Crucifix is not among these images. It is not as if the Cross was unimportant to early Christians. Saint Paul preaches on the centrality of the Cross to the Christian faith, “But may it never be that I would boast, except in the Cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, through which the world has been crucified to me, and I to the world” (Galatians 6:14).

In his writing on the sign of the Cross, Tertullian (160-240) mentions the way Christians would look for crosses throughout their day in windows and in floor markings. Other early Church Fathers preached the glory of the cross too. Hippolytus (170-276) of Rome wrote:

The Church is like a ship tossed in the waves…Moreover, she carries the trophy over death, the Cross of the Lord, in her midsection. ... The ladder in her leading up to the sailyard is a symbol of Christ's Passion, which allows the faithful to ascend to heaven.

Still, the Cross was not something easily explained to outsiders. As Saint Paul said, “we preach Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and folly to Gentiles” (1 Corinthians 1:23).

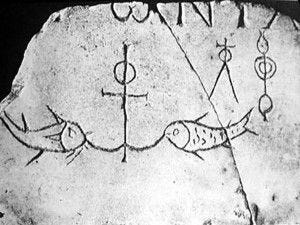

Death by crucifixion was reserved for the worst of non-citizen criminals. The word itself was used as a curse. While we are accustomed to seeing artistic crosses in churches and homes, early Christians may have been accustomed to seeing or hearing about actual men, including their friends, the martyrs, dying by crucifixion. Thus, with the painful reality of crucifixion still legal and fresh in their memory, early Christians only depicted the Cross symbolically with anchors and later with gems as a trophy of victory.

After Christianity was legalized and crucifixion outlawed, Saint Helena, Constantine’s mother, pilgrimaged to Jerusalem in 320 AD to search for the true Cross. She found it there, buried under the temple of Venus, which the Romans had built over Golgatha to prevent Christians from visiting the holy site. From that time on Christians began to gather to venerate the true Cross on Good Friday. The nun Egeria recounts the veneration of the Cross ritual she attended in the fourth century.1

Saint Helena sent pieces of the Cross throughout the empire, and the practice of venerating relics of the Cross spread throughout the Christian world. On Good Friday, many Christians venerated relics of the true Cross which were encased in golden bejeweled containers. One example is the reliquary Cross commissioned by the Roman Emperor Justin II (520-570). The hymn Vexilla Regis, which is still sung during Passiontide Vespers, was written on the occasion of the arrival of this reliquary to Radegund, the Queen of the Franks.

The banners of the King are marching forth

Refulgent the emblem of the cross and its mystery,

In the flesh was the Creator of the flesh

Splayed onto a crossbar;

Wounded by the direful point of a lance

That He might wash us from our sins,

Flowing forth a wave of water and blood.

O, Cross, hail, our one hope,

In this time of the Passion

For the pious, increase grace

And from us sinners, take away our guilt2

These magnificent crosses were symbolic signs of victory, called crux gemmata. Thus, they are presented with jewels or amidst Paradisal gardens. In the crux gemmata, Christians reclaimed the Cross, demonstrating how for them it was not a sign of shame but a trophy of their redemption and eternal victory.3

Eventually artists began making images that depicted the crucifixion. Still, the first crucifixes did not focus on the suffering of Christ, but on his victory over death. In one of the earliest surviving images of a crucifix, Christ’s crucifixion is depicted next to Judas’s suicide. A snake slithers under Judas, alluding to the serpent of Genesis which Christ has crushed on the cross, bearing our sins and reversing the curse of Adam. While Judas is dead, Christ is alive and serene. His Cross is marked “King of the Jews.” This image presents the truth of Christ’s crucifixion and his Resurrection. Although Jesus died on a Cross, he rose from the dead and reigns eternally in heaven. Thus, Jesus is depicted naked, as the victorious Greek athletes were in images of their divine elevation (apotheosis). In the fourth panel of this casket (below), the artist boldly proclaims Christ’s Resurrection with an image of Thomas putting his finger into the side of Jesus’s risen body.

During the iconoclasm of the seventh and eighth centuries, images of the crucifixion recede again in the East; however, some crucifixes from this time survive. Saint Catherine’s monastery, the oldest continuously inhabited monastery in the world, still holds many icons from this period, including this eighth century crucifixion icon. During and after this iconoclasm, iconographers used their art to fight back against Christological heresies.

In contrast to earlier images of the crucifixion, Christ’s eyes are closed here. This icon of Christ’s crucifixion emphasizes his death, refuting heresies which denied the full humanity of Christ. The black void of a background projects the Crucifix all the more dramatically into our space. Blood and water, which St. John Crysostom says are signs of the two sacraments which fashioned the Church, the Eucharist and Baptism, flow from Christ’s side making clear the reality of his death on a cross. His eyes expressively droop down, depicting the sorrow of his death. Here, Jesus is painted with a halo and a purple colobium, symbolizing his roles as priest, king, and sacrifice.

Mary and John stand at his feet in mourning, but their clothing and countenance convey the eternal reality of their own eventual victory. Below the Crucifix, soldiers cast lots for Christ’s garments. At the top of the image, the angels, signs of his divinity, welcome Christ into paradise. The sun is painted on Christ’s right with the good thief and the moon on his left, pointing to the fact that Jesus is king of the cosmos, and that the cross is its axis. Even the crown of thorns appears to be made of stars. This division of right and left, sun and moon, also represents the New and Old Testaments. The symbolic division continues in Western art up to the Gothic period.

Early medieval crosses do not shy away from depicting Christ’s death and suffering; however, they also incorporate Old Testament typology and various Biblical symbols which had already been articulated in hymns and theological texts of Church Fathers.

In this Crucifix, a reliquary of the true Cross crafted at Hildesheim, Christ’s golden body hangs in front of an image of the victorious Paschal lamb from Revelation, slain but standing. His head droops down, conveying his suffering, but the elaborate enamel floral patterning on the cross points to his victory and the belief that the Cross is the tree of life.

This idea was already prominent by the sixth century, when Fortunatus wrote Crux Fidelis, the hymn sung on Good Friday.

Cross faithful, among all,

The tree of single nobility.

No wood such a one profers

On its boughs, flower, and buds.

Sweet the wood, sweet the nails

Sweet the weight it bears.Strike praise, my tongue, glorious

The battle’s struggle.

And around the cross’s trunk

Speak forth His triumph noble.

How as Redeemer of the world,

He was slain in sacrifice and still victorious.4

Four enamel images on each end of the beams depict scenes from the Old Testament which point to the Cross. One image helps us to see that Christ is the slain lamb without blemish whose blood is a sign of our redemption. Another, the bronze serpent, helps us to see the Glory of Christ on the cross. Christ himself makes the allusion to bronze serpent, “Just as Moses lifted up the snake in the wilderness, so the Son of Man must be lifted up, so that everyone who believes in him may have eternal life (John 3:14-15).

During the late Middle Ages, images of the Cross began to reflect the Franciscan spiritual emphasis on engaging emotionally with the stories of the Passion. Thus, these images reflect the intensity of Christ’s suffering and draw us emotionally to the narrative of Christ’s passion.

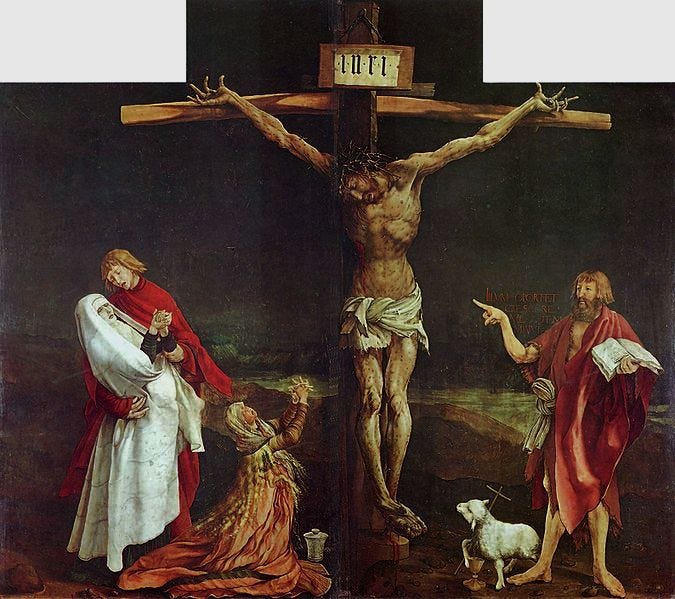

The Isenheim altarpiece is perhaps one of the most iconic examples of this kind of Crucifixion scene. Grunewald painted this giant altarpiece for a hospital in Italy which tended to patients afflicted with a disease which caused painful sores to erupt all over their bodies. Grunewald lived in the hospital while painting it, contemplating Christ’s crucifixion as he witnessed the horrible pain of the patients surrounding him.

In the altarpiece Christ himself is shown to suffer the very disease the hospital’s patients did. Thus, the image gave the sick a powerful reminder that “he has born our griefs and carried sorrows” (Isaiah 53:4). The image also would have helped the monks at the hospital to see Christ in the sick and suffering.

Christ’s hands are in some ways the most horrifying part of the image, writhing as they do beneath the excruciating pain of the nails which pierce his palms. Mary, Mary Magdalene, John, and John the Baptist stand with him, along with the victorious lamb, whose blood pours out into the Eucharistic chalice. The altarpiece opens to a glorious depiction of the Resurrection, a powerful image of hope. Christ’s face shines with an otherworldly light which illuminates the pitch black background and anticipates the light of the second coming and his Eternal Kingdom.

This last Crucifix is painted by the modern artist, Georges Rouault, a French painter of deep faith. The deep black curved lines, which resemble the lead of stained glass windows, seem to reverberate with sadness; and yet, the luminous, gem toned colors shine through and point to the light of the Resurrection. Hints of light already pierce the sky behind him. In this image, the compassion of Christ is communicated through the warm tones of his body and the gentle elongated lines of his face. His outstretched arms seem to shelter Mary and John, recalling the Psalm “He will overshadow thee with his shoulders: and under his wings thou shalt trust” (Psalm 91:4). This image reflects the fact that the sacrifice of Christ on the cross, is truly a sign of his merciful love for us.

Blessed Good Friday and Happy Easter!

Sources:

Jensen, R. M. (2017). The Cross: history, art, and controversy. Harvard University Press.

Schiller, G. (1971). Iconography of Christian Art: The passion of Jesus Christ. United Kingdom: Lund Humphries.

"Then a chair is placed for the bishop in Golgotha behind the Cross, which is now standing; the bishop duly takes his seat in the chair, and a table covered with a linen cloth is place before him; the deacons stand around the table, and a silver-gilt casket is brought in which is the holy wood of the Cross. The casket is opened and (the wood) is taken out, and both the wood of the Cross and the title are placed upon the table. Now, when it has been put upon the table, the bishop, as he sits, holds the extremities of the sacred wood firmly in his hands, while the deacons who stand around guard it. It is guarded thus because the custom is that the people, both faithful and catechumens, come one by one and, bowing down at the table, kiss the sacred wood and pass on. And because, I know not when, someone is said to have bitten off and stolen a portion of the sacred wood, it is thus guarded by the deacons who stand around, lest anyone approaching venture to do so again.” (Pilgrimage of Egeria)

https://abbeyofreginalaudis.org/liturgy-exsultet.html

Thank you very much for such a wealth of the cross art history. It is fascinating. I never knew the backstory of Grunewald’s altarpiece. I can appreciate it all the more now. God bless you and your family!

What a special treat on a day of fasting. Amelia if your substantial work finds an audience among our separated brethren they cannot help but seek a greater understanding of the beauty and truth that they have been denied for so long. LET'S HOPE SO!

Have a Blessed Easter!