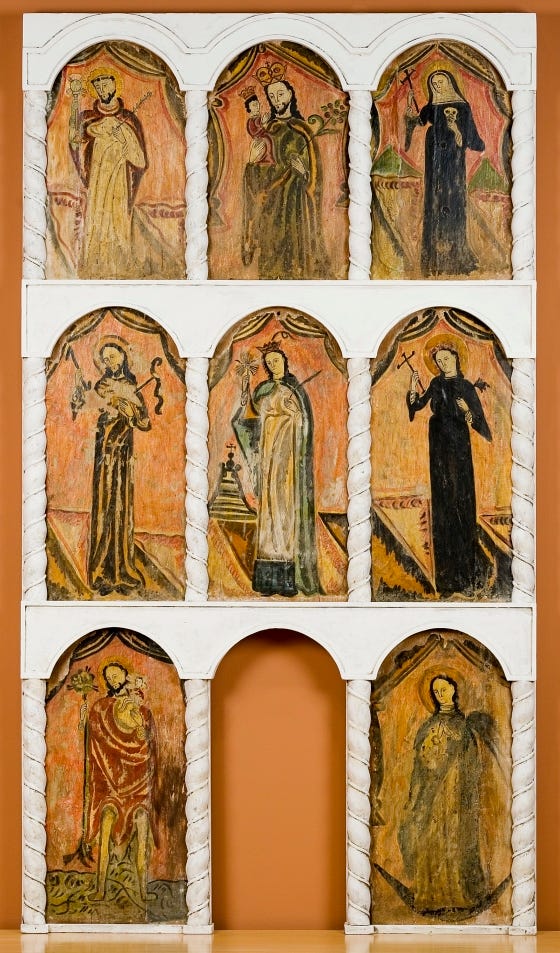

If you have ever been to the historic adobe churches or traditional Spanish markets of New Mexico, chances are you have seen the sacred images made by the santeros. The santeros, or “saint makers”, of New Mexico, began making these images (santos) for churches in the late 1700s. Before this, the Spanish had sent art from Spain and Mexico to decorate the mission churches. Eventually, Spanish money dried up, and the people of New Mexico began developing their own images to decorate their homes and churches.

Robert Shalkop articulates what makes the style so compelling:

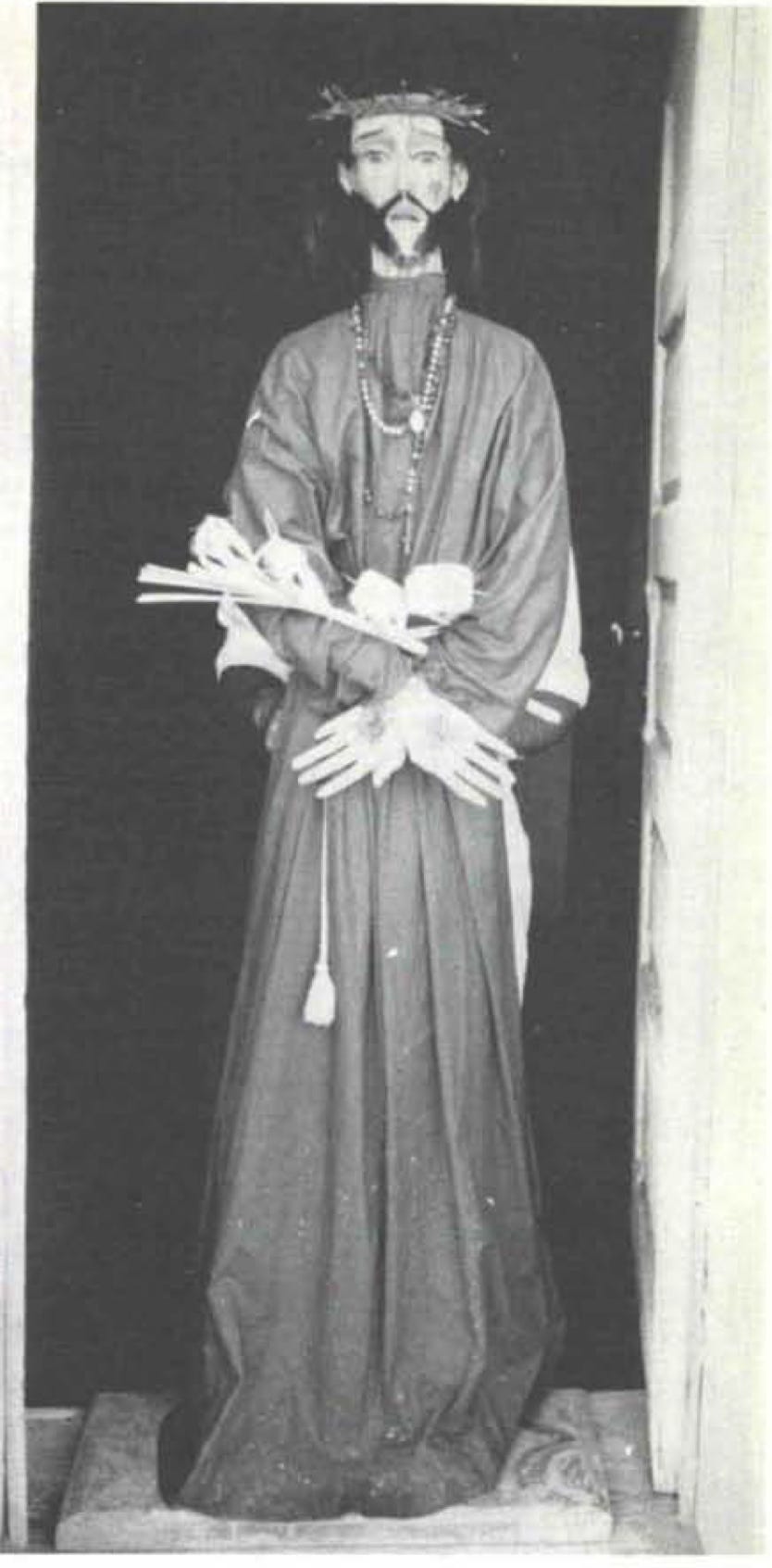

A meditative air is in fact one of the distinguishing characteristics of santos, even among the suffering Christs (See below). We do not find here the contorted features and violent gestures common among Mexican and European antecedents. At the same time, the inherent vitality and uncompromising sincerity of New Mexican figures is often startling. The most charming Madonna is never sugar-coated: the most dramatic Cristo is more than merely histrionic. Despite frequent smallness of size, these figures never remind one of dolls. There is always a restrained force that commands respect, and the conviction of the artist is unmistakable even when his skill is limited.1

Although the santero tradition emerged in the eighteenth century, and many of it’s first practitioners were Spanish missionaries, the images could not be more different from the academic style popular in Europe at the time. In many ways, the flat hieratic style, which is both simple and evocative, has more in common with art of the early medieval period, than the academic art of Europe. Many art historians have recognized this similarity, and Robert Shalkop called it “a final, unexpected flowering of medieval Christian imagery separated from its roots by half a world and a thousand years." Like the Romanesque artists and Byzantine iconographers, santeros sought to paint images that were windows to heaven.

The santeros made art to adorn churches, but they also labored away making hundreds of small images for the houses of poor villagers. Almost every household held retablos (small paintings on wood, tin, or hide) of various saints important to the family. These images were held in an esteemed place and passed down through the generations. If they broke or chipped, santeros would come by to restore them.

As Willa Cather relates in her excellent novel, Death Comes for the Archbishop, New Mexico was an isolated and sprawling diocese. The santeros were so important to families in part because priests were far and few between during the colonial period. Santos (images) or bultos (statues) aided the villagers in prayer and reminded them of the reality of the power of intercession and of the heavenly realm when they were not able to go to mass. Thus, the santeros had an esteemed spiritual role in the communities. In turn, the people expected the artists to live holy lives, believing that the images should reflect the character and prayerful process of the santero.

In colonial New Mexico, saints were woven into people’s daily lives through the liturgy, stories, prayers, and seasonal work. During the harvest, they would pray to Saint Isidore for intercession. During storms, they would pray to Saint Barbara. During droughts and famines, they would pray to Saint Rita. Among the people of New Mexico, Saint Rita of Cascia (1357-1481) was one of the most popular saints. Her image is among the most common in retablos, altar screens, and bultos (statues).

How did this fourteenth-century Italian saint become so well loved in New Mexico? Before she was known in the new world she was beloved throughout Europe and known for her many miracles. One hundred and fifty years after her death, her body was found incorrupt, and by this time many other miracles involving healings had been attributed to her intercession. Although she was not canonized until 1900, she was declared a blessed in 1626.

The Spanish especially embraced the Italian saint and dubbed her “Le Santa De Los Impossibles.” When the Spanish missionaries traveled to the new world, they told stories of Rita to the natives, who quickly embraced her as one of their own.

Perhaps the natives found comfort in knowing they could ask her to intercede for their impossible causes. The people of New Mexico were not shielded from the harsh realities of famine and violence, and certainly would have had many impossible causes to turn over to the Italian Saint. The fact that she was also the patron of women seeking husbands surely also helped her popularity among the people.

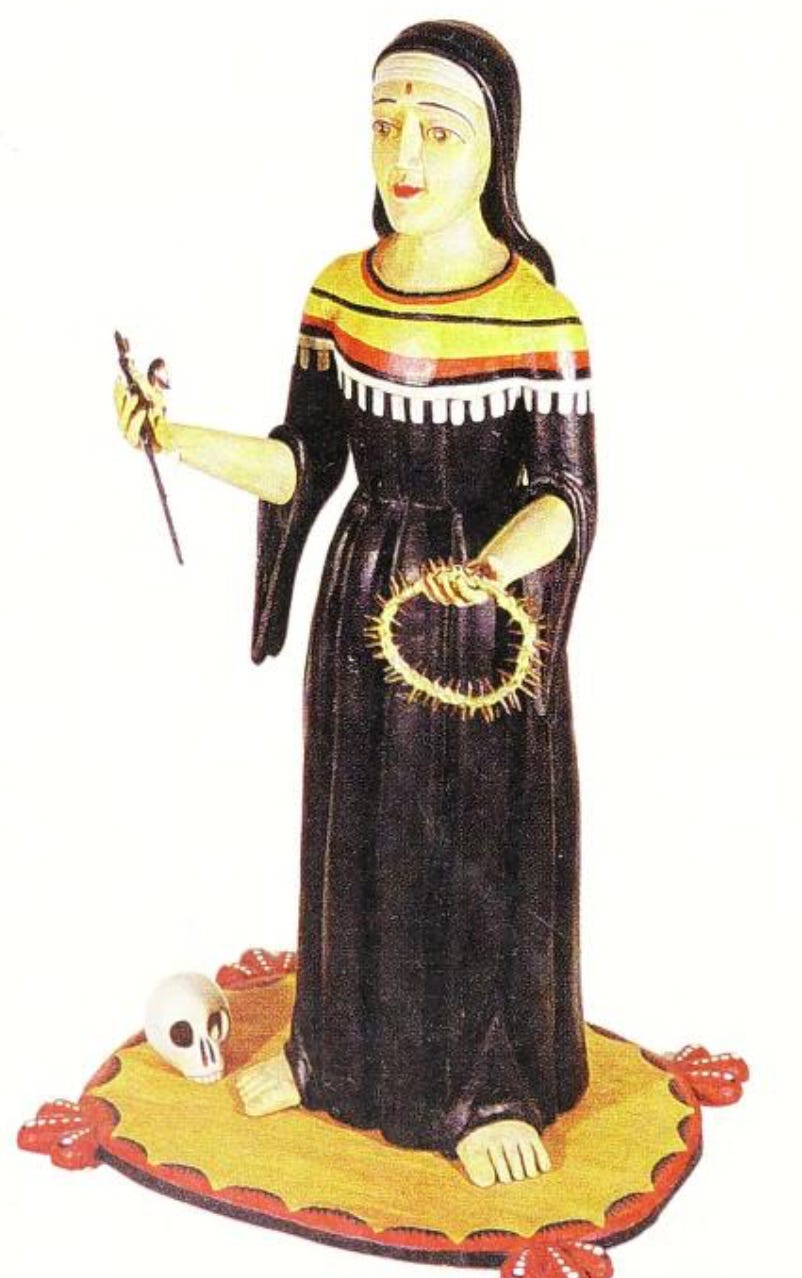

In the santos, she is pictured in a simple black Augustinian habit. Although Saint Rita wanted to be a nun from the time she was a small child, her parents forced her to marry. The marriage was not happy. Her husband was known to be an irascible man prone to violence. By Rita’s influence, he reconciled himself to God at the end of his life; however, he could not escape the sins of his former life and was murdered. Rita’s two sons vowed to avenge their father’s death, greatly disappointing their mother, who did not want them to commit the sin of murder. She prayed that they be spared of this sin. Her prayer was answered in a tragic way. Her sons did not murder their father’s killer but died of dysentery not long after their father’s death.

The reality of death was ever before Rita’s eyes. Thus she holds a skull, a memento mori, a reminder of death. However, she does not only hold a skull but also a cross, a reminder that Christ transformed death and suffering into glory and that we may unite our suffering with his.

After her sons died Saint Rita wished to enter the convent, but she was not able to because of the feuds her husband entangled her family in. Rita asked God for the impossible, praying for the intercession of Saints Augustine, John the Baptist, and Nicholas of Tolentino to end the feud. By the help of God, Rita was able to bring peace between warring families and was finally able to enter the convent.

In these santos, Rita often bears a mark on her forehead, a stigma that was given to her on Good Friday as she prayed before the crucifix. It is said that she suffered the marks of Christ’s crown of thorns. The wound was unsightly and festered on her forehead for the last fifteen years of her life. In this particular icon, an image of Christ with the crown of thorns appears, connecting her suffering with his.

By any account, Rita did not have a “happy” life in the way the word is usually meant. And yet, she appears happy, sometimes even smiling in the icons of the santeros. For the santeros did not need to show the people the reality of her earthly suffering, which they knew of too well. The artists depicted the reality of her heavenly and eternal beatitude. Her face glows with the light of Christ, transformed as she is by his grace. These images reminded the people of her eternal happiness, which was a fruit of the way she bore her suffering with love, uniting it to Christ’s.

She is usually pictured amidst bright colors, often cypress trees, symbols of resilience and eternal life. Sometimes, she is pictured with flowers or roses, an allusion to some of her miracles. When Rita first entered the convent, her superior assigned her to water a dried-up tree. For many seasons, Rita watered the tree in vain, and eventually, the tree began to bloom again and became known as the “saint's tree.”

Another story involved roses. When Rita was dying of tuberculosis, a relative visited her, asking if there was anything she could do for her in her illness. Rita asked for one thing—a rose from her garden. Although her relative was puzzled by the request—it was the dead of winter—she went to look for a rose for Rita. Sure enough, she found a rose blooming in the snow.

Among today’s traditional santeros, Rita remains a popular subject. Many of these painters still follow in the strict iconographic rules of the santeros, grinding minerals for paint and using the methods and materials of their forebearers.2

If you go to the traditional market in Santa Fe, you will still find many artists still committed to to this iconographic style which has now been preserved for hundreds of years.3 Novelty is not the aim of these artists, rather faithfulness is. The art of the santeros is at once an artistic expression particular to the people of New Mexico and a style that is in clear continuity with the Christian iconographic tradition. I hope that it is preserved for many more years to come and that Rita continues to hold an esteemed place in the tradition.

Sources:

Awalt, Barbe, and Paul Rhetts. 1998. Our Saints Among Us: 400 Years of New Mexican Devotional Art. Albuquerque, NM:LPD Press.

Connolly, Richard. 1903. Life of St. Rita of Cascia, O.S.A. London: Washbourne. https://archive.org/details/life-of-saint-rita-of-cascia-osa-by-father-richard-connolly-osa-dd

https://www.fisheaters.com/feastofstritaofcascia.html

Samuelson, Susan. "Thieves Ravage New Mexico's Heritage." New Mexico Architecture 14, 5 (1972). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nma/vol14/iss5/3

Steele, Thomas J. S.J. 1994. Santos and Saints: The Religious Folk Art of Hispanic New Mexico. https://archive.org/details/santossaintsreli00thom/page/n2/mode/1up

Samuelson, Susan. "Thieves Ravage New Mexico's Heritage." New Mexico Architecture 14, 5 (1972). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nma/vol14/iss5/3

Altar screens were painted on pinewood while smaller images, called retablos, were painted on tin, pinewood, or animal hide. First, the santeros would coat the surface with a gesso glue made from animal lard. After this coating, they would paint with a hand made water-based tempera which was thickened with gum from vegetables and colored with various minerals from the area.

See more from contemporary artists: https://potrerotradingpost.com/SanteroArt.html

There's a shrine of St. Rita of Cascia in Philadelphia, Penn., that I've visited a handful of times over the years. Lots of artwork there, too! https://www.saintritashrine.org/

This is so familiar to me - like going home. I only spent 5 years in New Mexico - Albuquerque - but the entire state is full of such images and they enter deeply into one's soul. Even among atheists and non-believers, almost every New Mexican has a colorfully decorated cross or a retablo in the home. It's cultural for them, being proud of being from the state and its culture, but there are many for whom these works of art are still very important spiritually. During Holy Week, you will see penitentes crawling on their knees - sometimes with awful-looking penitential ropes and such - from Albuquerque to Chimayo, which you mentioned in your post. You will see them kneeling or walking the long distance, using the side of the highways to get to their destination. Chimayo is the source of many miracles and there's a story about that too!