At one time, November 11th was one of the most festive holidays of the Christian year, a kind of Mardi Gras before Advent where livestock were slaughtered and great feasts were enjoyed. People gathered on this day to celebrate Saint Martin of Tours (d. 397), the great Gallic bishop and the first non-martyr to be recognized as a saint by the Church. Almost every Gothic cathedral has a window dedicated to the great French saint known as the “thaumaturgist,” or miracle worker of the West. Even in the 20th century people thought enough of him to end World War I on his feast and make November 11th Veterans day .

Martin in Chartres

In Chartres Cathedral, there are no less than seven different places where Martin’s story is rendered. For the medievals, Saint Martin of Tours paradoxically represented both the chivalric gentility of the honorable knight and the wild asceticism of the holy monk and miracle worker. In many ways he was the saint par excellence of the French Gothic so it is fitting that he appears so often in Chartres Cathedral, that great emblem of this age.1

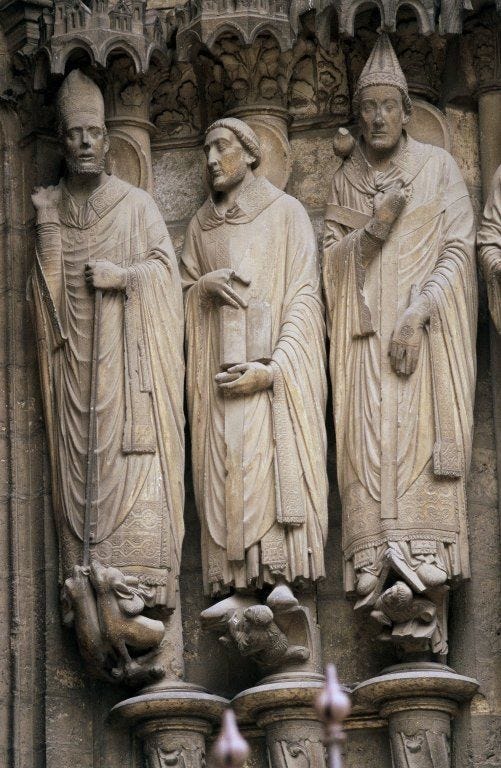

An elegantly solemn figure of Saint Martin stands with other confessors who seem to hold up the Church and welcome pilgrims entering the doors of the South porch. Here, Martin’s cheeks are gaunt, his mouth agape, and his eyes fixed ahead; two dogs playfully lick his feet, slightly offsetting the austerity.

The famous scene called “the charity of Martin” appears most frequently in the art of the age. In Chartres you can find it on the tympanum above the south porch doors, on a clerestory window, on the life of Martin window, and in a statue by the altar.

That this event is repeated so often is not surprising. The medievals were great lovers of repetition and pattern. This is how they learned to recognize the saints and the stories in the Bible. Though the saints are diverse in their temperaments and offices, they all lived in the pattern of Christ, so in the windows we see the saints living in this pattern. Their stories all resemble his in some way because they find their fulfillment in him. The images of Christ are a key to all the windows of the saints and Old Testament figures in the Cathedral.

Stained Glass as “the Poor Man’s Bible”

We are so separated from this symbolism today that it is hard to believe a peasant could really read the windows as “a poor man’s Bible.” But he could, though not in the linear way we read a book from beginning to end. The windows are something you marvel at and allow to wash over you. When you look at a particular window in a cathedral you take in the whole life of a saint, seeing the pattern of his or her life as God sees it.

In returning week in and out to the Cathedral one would come to grasp the patterns in the lives of the saints and see how they fit the pattern of Christ’s life. In Martin’s window we see him baptized, captured by robbers, healing the sick, kissing lepers, raising the dead, preaching, and expelling demons. All of these miracles echo Christ’s in the Gospels, though Martin’s particular story was known through the Golden Legend 2. The miracles highlighted in his window are present in different ways all over the Cathedral. The common canons and symbols used by the Gothic artisans make these patterns remarkably legible for the common man. Emile Mal describes the narrative style of these windows:

The essential only is retained in each episode, and only a small number of figures in lifelike attitudes is placed in one medallion…Decoration is reduced to a minimum--a tree, the gate of a town, or undulating lines which stand for rivers or the sea, mere signs to suggest the place in which the scene takes place…One king resembles another, one soldier another. They are almost like symbols... These little pictures have the remarkable quality of lucidity and abstraction which we associate with the French classical drama.”3

This lucidity gives them the gem-like quality which is perfected by the light of the sun.

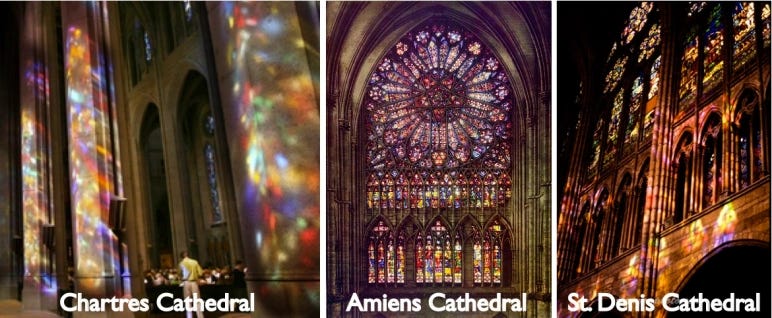

Light and Stained Glass

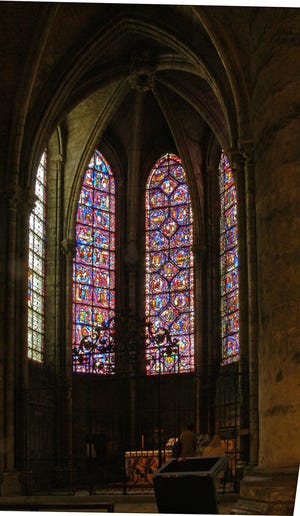

The brilliant colored glass of Chartres Cathedral shines like sun-filled jewels or flames of fire recalling the walls of the new Jerusalem “And the foundations of the wall of the city were adorned with all manner of precious stones.” (Rev 21:19)

Light penetrates the windows of the cathedral piercing the darkness with shafts of color and making visible the reality of the prologue to John’s Gospel, the reading which was read at the end of every mass. “In him was life, and the life was the light of men. The Light shines in the darkness and the darkness has not overcome it.”4 (John 1:4) By marveling at the way colored light dances on stone, we remember that Christ is “the father of lights” (James 1:17).

The significance of light in medieval thought cannot be overstated. After all, creation began with God’s dictum: “let there be light” (Genesis 1:3). In their theology of light, medieval thinkers relied heavily on the thought of the Eastern mystic, Saint Denis the Pseudo-Aeropagite who taught that “Creation is the self revelation of God. All creatures are "lights" that by their existence bear testimony to the Divine Light.” The light of Christ shines through a thing “by the degree that it partakes in the light.”5

The luminosity of the glass during the day points to how radiantly the light of Christ shines through the Bible and through the saints, the true gems of the church.

Stained glass windows were meant to reflect many truths of the faith and lift the mind and heart to God. Art makes visible the liturgical reality of the mass and these windows remind us that the angels and saints are present during the celebration of the Mass. It is hard to summarize the purpose of the windows in one sentence as they synthesize so many brilliant truths. A pilgrim looking at the Martin window may contemplate the way the light of God light shines through the saint. He may also contemplate the ways in which the saints and prophets take part in the pattern laid out by Christ. Perhaps he thinks of how Saint Martin could intercede for him or maybe he merely delights in familiar stories he sees in the window from the Golden Legend.

Life of Martin

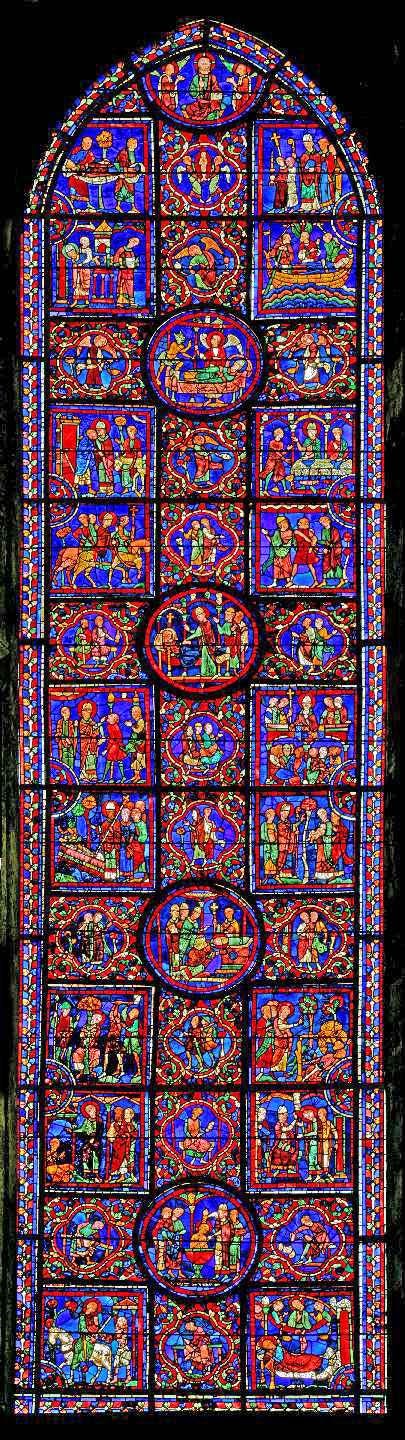

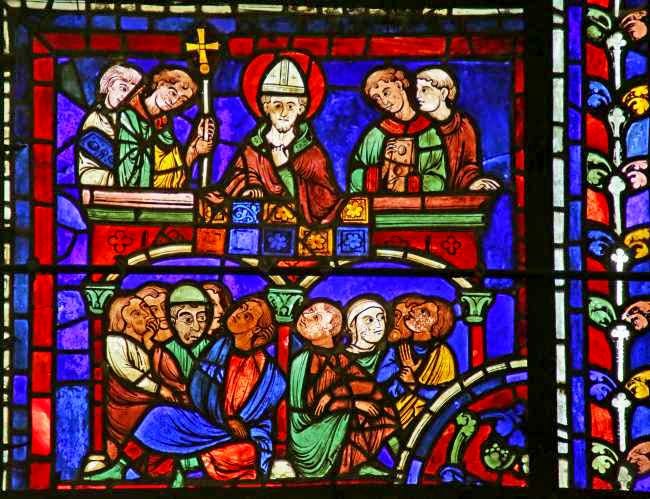

The great Martin Window, made up of forty scenes, is inspired by stories from the Golden Legend as well as from Sulpicius Severus’s biography. It is in the ambulatory of the church along with other windows dedicated to the confessor saints. The placement of these windows so close to the altar reflects their great importance. It is light from these windows that shines on the altar.

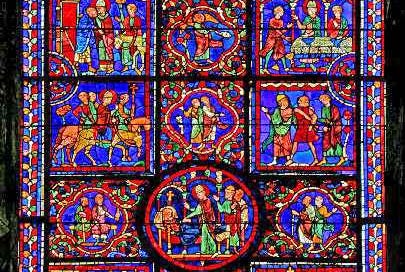

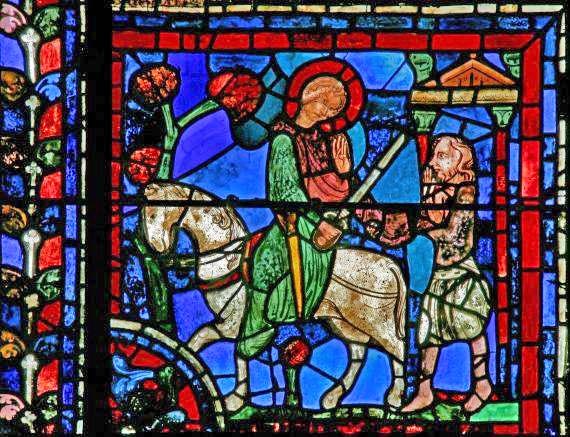

The story of Martin begins at the bottom of the window with the best known event of his life, his great act of charity. On one of the coldest nights of the year, Martin, then an honored soldier, cut half of his cloak and gave it to a shivering beggar. Though this seems like a small thing, the act revealed how Martin was willing to humble himself in the eyes of his fellow officers to serve God. This small act of charity opened Martin to the incredible grace of God which would transform his life. In this miracle, we see how every small act of love is recognized by God and helps to open our hearts to receive further grace.

When Martin went to sleep with only half his cloak he: “heard Jesus saying with a clear voice to the multitude of angels standing round — Martin, who is still but a catechumen, clothed Matthew 25:40 me with this robe.”6 The scene recalls mystic dreams of the Bible, like those of the Josephs, and puts Martin in the mold of these great saints. The sleeping Martin also resembles Jesse from the famous Jesse window and connects Martin to those great ancestors of Christ.

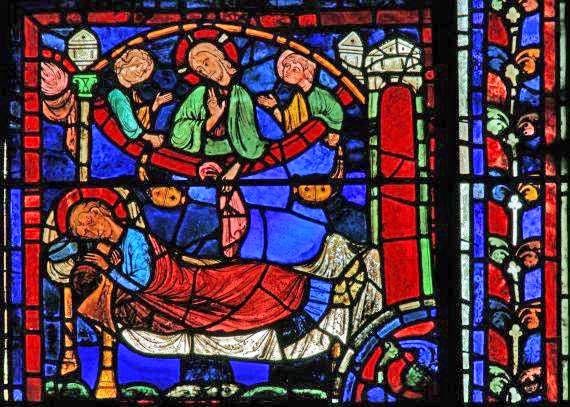

Conversion and Baptism

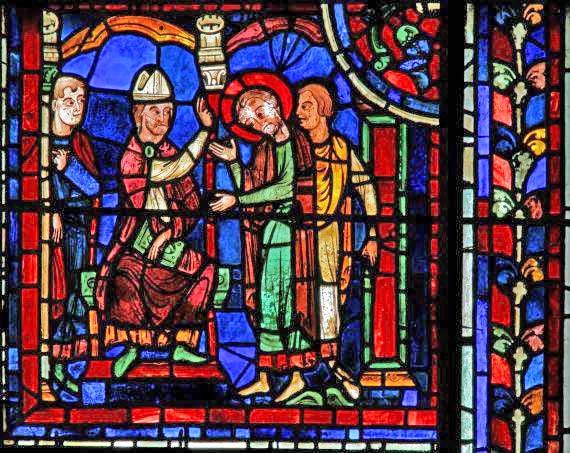

In the story and in the window, Martin hastens to receive Baptism. Above, he disrobes himself of his military attire and allows himself to be clothed with Christ in Baptism. The baptismal font appears as a red chalice reminding us of how in Baptism we are brought into the Passion and Death of Christ as well as his Resurrection. The centrality of this scene and the numerous other scenes of Baptism throughout the Cathedral make visible the truth that Baptism is the door to salvation.

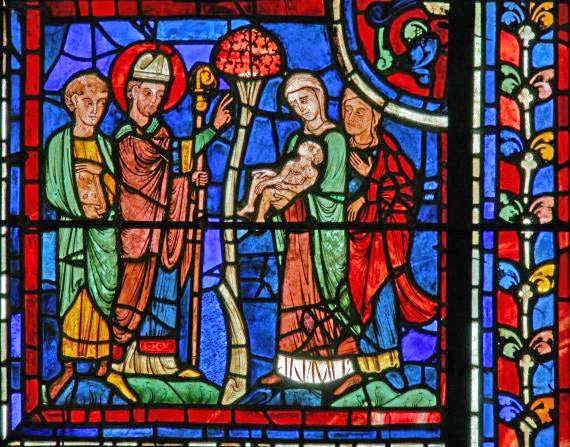

In the next panel, Martin revives a dead catechumen so he could receive the sacraments before death, and in panel 8, Saint Hilary of Poitiers, the great “hammer of the Arians,” blesses Martin. Indeed it was Hilary who recognized Martin’s gifts of discernment and designated him as an exorcist. This blessing also foreshadows Martin’s own destiny to become a bishop.

The bottom panel is not complete without the four leather workers surrounding Martin, for it was the cobblers who donated this window. Here, one bends over as he labors. His presence in the window shows how our daily work may help to build the kingdom of heaven, as the cobblers helped to build the Cathedral with their offering. The window reveals how God transforms small labors into heavenly glory, as he has transformed the small act of Saint Martin into a great sign of Charity.7

Martin’s escape and healings

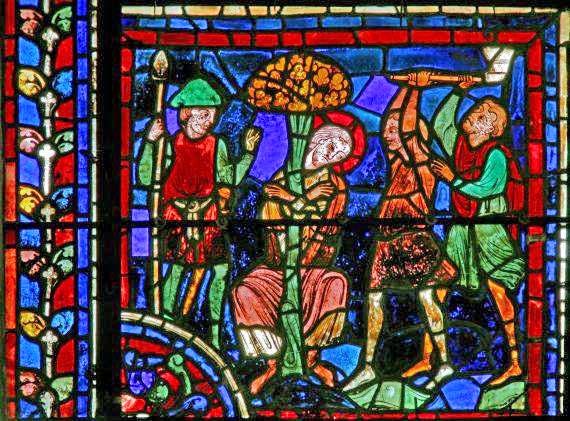

Not long after finding Saint Hilary, Martin escaped certain death on two occasions, first at the hands of robbers who captured him on the way to evangelize his parents and second at the hands of tree-worshiping pagans. The first scene of Martin’s capture by robbers echoes the scene in the famous Good Samaritan window where the man is beaten and left for dead. Martin escaped by evangelizing one of the robbers who was impressed with Martin’s peaceful demeanor and set him free. That Martin is tied to a tree is also significant and the image connects Martin’s sufferings to Christ’s on the cross.

When Martin threatened to cut down the sacred tree of the pagans, the heathens tied him to it and prepared to cut the tree to fall on Martin. Instead the tree, by the power of God, fell right above the heathens, before diverting and sparing them. They too converted after witnessing this miracle. The tree recalls how the cross of Christ is the tree of life that brings life to all men and conquers the heathen gods of nature. In the medieval view all creation serves God and sings his praise.

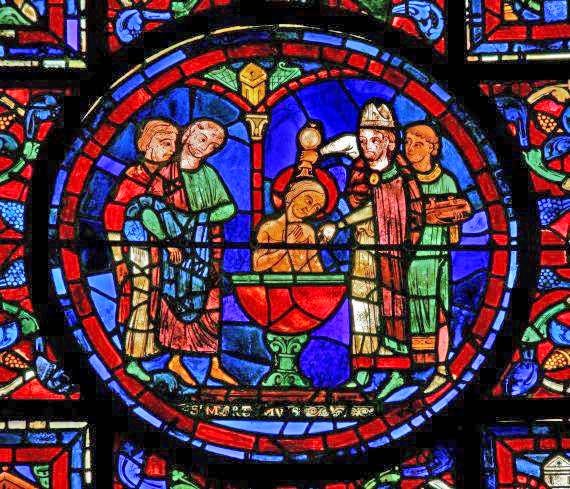

Although Martin had no wish to assume esteemed offices, the people of Tours so fervently begged for him to become bishop so much that he eventually submitted. The large roundel above features another central event in Martin’s life, his ordination as bishop. Martin lays his head before the altar as other bishops anoint him symbolizing the way he offers his life as a sacrifice to Christ. Another cleric holds a cross and the Bible, two great weapons of the faith. From now on Martin is featured with the bishop's crosier symbolizing the bishop's role as shepherd and the double pointed mitre symbolizing the inspiration of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost and the wisdom of the Old and New Testaments.

As bishop, Martin lived as a monk and interacted frequently with the people of his diocese. In the scene above, Martin investigates the tomb of a supposed martyr where he discovers from a shade that the person was actually a robber. Onlookers witness Martin’s miracles, reminding us how many witnesses there were to his many miracles and holy life.

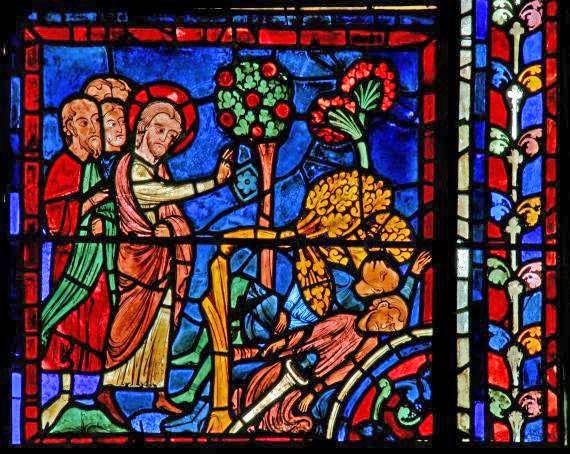

During his Bishopric, Martin traversed his diocese ministering the sacraments, curing the sick, exorcising demons, and preaching. In the above scene, Martin blesses and revives a child that had died. A tree stands between him and the child reminding us that it is by the power of Christ and his cross that Martin revived the child. The panel below shows one of Martin’s many exorcisms. Perhaps this is the one where Martin put his fingers in the mouth of the possessed man:

But when he continued to gnash with his teeth, and, with gaping mouth, was threatening to bite, Martin inserted his fingers into his mouth, and said, If you possess any power, devour these. But then, as if red-hot iron had entered his jaws, drawing his teeth far away he took care not to touch the fingers of the saintly man.” Immediately after, the demon fled.

In the scene above, Martin preaches to his congregation, reminding us that a key role of the bishop is to instruct the faithful in matters of faith. That Martin’s body is represented by the church building is a visible reminder that a bishop is “a symbol of all that binds the community into a single body in the Lord.”8 In the scene below, Saint Martin heals a young paralyzed girl, responding to the persistent requests of her distraught father. The artist cloaks her with gold which symbolizes the way the grace of God has healed her.

These exorcism and healing miracles find parallels in the Gospel healings of Christ and remind us that Christ continues to heal those who have faith in the power of his mercy. The scene below is one of the most touching scenes of the whole window and is an emblem of Martin’s closeness to the poor. Jacob De Voragine recounts: “Martin was a man of deep humility. In Paris he once came face to face with a leper from whom all shrank in horror, but Martin kissed him and blessed him, and he was cured.” A bright red gate draws attention to the scene giving it a kind of intensity.”9

In the last miracle depicted, the artist highlights Martin’s priestly duty to dispense the sacraments, the source of healing for the people of God. Aelfric gives an account of this miracle in his homily on the saint. In his account Martin blessed some oil in a glass ampulla for a sick woman, but before he could administer it a boy accidentally knocked it on the floor. Miraculously the glass did not break and Martin was able to deliver the oil.10

Martin’s Death and the Transfer of his Body

Finally, the last panels depict the death and funeral of Martin. In them we see Martin’s Angel protecting him from a demon. Angels surround these scenes and remind us of their ministering role at the moment of death. That so many panels are dedicated to his death show the liturgical importance of the rites for the dead, where death is acknowledged and people gather to pray for God’s mercy upon the soul of the dead.

After Martin’s death, the people of Poitiers and Tours argued over who would keep the body of the saint. Eventually, the monks were made to transfer Martin’s body from the monastery he lived in at Poitiers to the Cathedral where he served as Bishop at Tours. One of the last panels shows Martin at rest, traveling by ship to his burial on a rainbow sea. Death here is a passage to new life. The rainbow reminds us of God’s promise and glory, which is now Martin’s glory. Angels carry his soul to heaven as the Bishop of Tours receives the body of the saint in a solemn procession.

Finally it is Christ who tops the window and sees over the saint’s life. It is at this point that we as viewers contemplate the whole window once again, the whole pattern of St. Martin’s life. Flanked by his angels, Christ is enthroned at the highest point and orders the window like he orders the Cosmos. A notable detail, Christ’s cloak in Heaven is the same color as the one that Martin gave to the beggar at the beginning of the story. It reminds us that Martin’s great Christian adventure started with a small act of charity. How many opportunities do we all have to do something similar for the least of our brethren? Such a small act can open us up to greater grace than we can imagine. Martin ascended the holy mountain up to Christ by God’s grace; may we also be blessed to follow his footsteps with Christ as the architect of our lives.

Which panel is your favorite?

Have you ever been to Chartres? What was your experience of the Cathedral?

How does stained glass help you to contemplate Christ in your own life?

If you are interested in Chartres I highly recommend this excellent and brief documentary.

https://www.christianiconography.info/goldenLegend/martin.htm

Emile Mal, The Gothic Image, p. 282

Otto Von Simpson, The Gothic Cathedral: Origins of Gothic Architecture and the Medieval Concept of Order; p. 53

Von Simpson, p. 53

Sulpitius Severus, On the Life of Saint Martin, ch. 3

See Anne F. Harris, "Stained Glass Window as Thing: Heidegger, the Shoemaker Panels, and the Commercial and Spiritual Economies of Chartres Cathedral in the Thirteenth Century," Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art I

(2008). https://doi.orq/10.61302/MGAM3152

https://www.catholicculture.org/culture/library/view.cfm?recnum=898

https://www.christianiconography.info/goldenLegend/martin.htm

Aelfric’s Homilies, ed. Thorpe, ii, 498

i went to chartres this past pentecost with 20000 other catholics on pilgrimage.(HIGHLY RECOMMEND !!!)

i wept when i saw it. it also reminded me of when i first saw the cathedral by chance while viewing kenneth clarkes civilization doku as a young man ehile dogsitting in memphis TN. this series made me want to be catholic and be apart of the civilization depicted therein. this framing and memory made it all the more surreal to be there, to be catholic, and to be 20000 strong. another midwesterner convert/european immigrant i met walking with the austrians the day before found me amongst the masses standing in front of the cathedral and i said to him, its wild to get to see this as an american, thinking of my great grandparents who rarely if ever left their farms. he looked at the facade for a moment and then looked back at me with the same teary eyes i was wielding. theres nothing like europe!

I'm fortunate enough to have been to Chartres twice, visits more than 20 years apart, and both times Malcolm Miller was there! I haven't been since the recent renovations, so I hope to be able to return.

You mention this was once a day of feasting. I believe it also marks the start of a traditional fast until Christmas.

Lovely post. Thank you.