Saint Luke and the Ottonian Renaissance

The wild-eyed visionary from The Gospels of Otto III

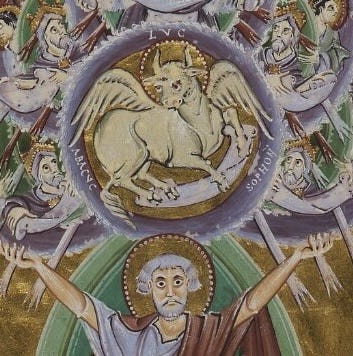

This wondrously sublime illumination of Saint Luke the evangelist captivates and confounds the imagination. It is but one illustration in the famous Gospels of Otto III. I will come back to Luke, but first I am going to explore the little known origins of this extraordinary work of art.

Over one thousand years ago, Benedictine monks at the island abbey of Richieneu, located at the confluence of Austria, Germany, and Switzerland, wrote and illuminated this magnificent Gospel book. It was one of many manuscripts that came out of the Richeneu scriptorium, but is probably the best known. It’s not a stretch to say that this abbey was one of the cradles of western civilization. At the time this Gospel was made, the scriptorium at Richieneu boasted the largest library in the west.

For centuries, Richieneu was one of the artistic centers of Europe along with the abbey at Hildesheim which I previously wrote about with

here. Art historians call this period the “Ottonian Renaissance” because of the artistic and cultural riches produced during the reign of the Ottos (919-1024), the Germanic kings who understood themselves to be the inheritors of the Holy Roman Empire from Charlemagne and the Byzantine Empire. The Emperors provided the patronage for these great works of art; however, Christian mysticism provided the inspiration for the creative outpouring that came from the abbeys.“They sought to build for themselves a peaceful, secluded, sanctifying world of prayer, study, and manual labor. In so doing, they built up an entire civilization.”-

The Ottonian art style evolved directly out of Carolingian, continuing to blend classical Roman, Byzantine, and early western Christian influences - especially Insular and Hiberno-Saxon styles - with a renewed emphasis on religious and imperial themes. Ottonian art is all about richly decorated manuscripts, intricate metalwork, and monumental architecture, serving both as a continuation of earlier traditions and a precursor to Romanesque art.

The Gospels of Otto III are not the first illuminated Gospels made by Benedictine monks. However, they are unique in the way they portray the evangelists as wild-eyed visionaries rather than collected scholars. In this illumination, which opens the Gospel of Luke, the evangelist ecstatically lifts up “that great cloud of witnesses” that hold Old Testament figures Ezekiel, Nahum, Habakkuk, Sophinias, and David. Angels and tongues of quivering light surround the crowned prophets. David and Luke sternly stare ahead at the viewer or the gospel text while the other prophets look to David and the Ox. Out of the figures, only Luke is fully depicted, reflecting the idea that he alone received the fullness of truth in Jesus Christ.

Books of the prophets lay open on the evangelist’s lap. Assisted by a mystical vision, Saint Luke incorporates the prophets with his knowledge of Christ as he presents his Gospel. The bright gilded background behind him accentuates an atmosphere of mystic fervor. This feature certainly echoes Byzantine icons; however, the expressive brushstrokes of this Ottonian image give it a unique and vibrant intensity.

The illumination reminds us that the Gospels are not just historical documents to be analyzed but Mysteries to be encountered with awe and reverence. Cold rationalism will not get us very far in apprehending the Gospels. They contain mysteries too deep for us to fully comprehend. And yet, Christ knows that we need something tangible to help us encounter him. The Gospel mysteries may overwhelm us, but they are also contained in something that we can touch, read, hear, and see.

Eliza Garrison notes this in her description of the illumination:

Indeed, Luke's figure, which grips in both hands a roiling cloud mass, makes especially clear that knowledge of God is something that can be touched; the two lambs that drink from the rivers beneath his throne indeed imply that his gospel can be imbibed and physically taken in.”1

The tactile quality of these illuminated Gospel Books, which were often gilded with a variety of jewels and other precious metals, reminds us of the physical quality of the Gospels. In Otto III's day, a book was a manifestly physical thing, created to last for generations. These books, as objects of awesome beauty, also remind us that Scripture is not just something to be read or heard but something that we actually venerate.

As Dei Verbum asserts:

The Church has always venerated the divine Scriptures just as she venerates the body of the Lord... The power and goodness in the word of God is so great that it stands as the support and energy of the Church, the strength of faith for her sons and daughters, the food of the soul, a pure and perennial fountain of spiritual life.2

Below the rivers, the inscription reads: “font patrum ductas bos agnis elicit undas” which translates to “From the source of the fathers the ox brings forth a flow of water for the lambs.” Luke is the ox who brings forth the Gospel and nourishes the Church with the text he wrote, inspired by the Holy Spirit. But the ox is also Christ himself, the sacrifice.

Church fathers understood the ox to represent Luke because of the way his gospel emphasizes Christ’s sacrificial role, and begins and ends in the temple. Scripture scholar Cornelius A’ Lapide S.J. (d. 1637) explains:

Moreover, among the faces or forms of the four Cherubim, the third, that of the ox, is ascribed to S. Luke, as well because he begins from the priesthood of Zachariah, whose chief sacrifice was an ox, as because he underwent the labors of an ox in the Gospel and bore about continually in his own body the mortification of the Cross for the honor of the name of Christ, as the Church sings of him.3

The arch framing the scheme, held up by Corinthian columns and covered in floral greenery and ribbons, also points to the temple imagery within Luke’s Gospel.4 A bird sits in each corner within a vine that seems to sprout from the arch. In Old Testament temples, the Holy of Holies was constructed as a reimagined Eden, and the columns were often covered with carved vines.

This illumination recalls the apocalyptic visions in which the ox appears in Ezekiel and Revelation.5

Around the throne, and on each side of the throne, are four living creatures, full of eyes in front and behind: 7 the first living creature like a lion, the second living creature like an ox, the third living creature with a face like a human face, and the fourth living creature like a flying eagle. 8 And the four living creatures, each of them with six wings, are full of eyes all around and inside. Day and night without ceasing they sing,

‘Holy, holy, holy,

the Lord God the Almighty,

who was and is and is to come.’6

Both books contain apocalyptic visions that bring together various incomprehensible symbols and remind us of the majesty and otherness of God. The rainbowed mandorla surrounding Luke is a notable feature. As historian Liz James points out, the symbolism of rainbows was much different than it is today:

The rainbow is not a manifestation of [a] physical phenomenon, nor a part of the Old Testament covenant between God and men, . .. but a manifestation of divine light reflecting the glory of Christ and seen particularly in holy visions [for example, Ezekiel 1:28], a further indication of the unworldly nature of these rainbows.7

These rainbows were often used to depict Christ in Majesty or images of the Transfiguration. That Saint Luke is shown in the mandorla is certainly notable. Why would the artist portray Luke in the mold of Christ in glory? My guess is that the Eastern concept of Theosis, espoused by many Church Fathers, inspired the artist.8

Archimandrite George, a recent abbot of the Orthodox monastery at Mount Athos, explains it this way: “Having been endowed “in His image,” man is called upon to be completed “in His likeness.” This is Theosis. The Creator, God by nature, calls man to become a god by Grace.”9

In gazing upon the Glory of Christ Jesus, Saint Luke allowed himself to be bathed in heavenly grace. St. Paul’s Second letter to the Corinthians is also relevant here: “And we all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being changed into his likeness from one degree of glory to another; for this comes from the Lord who is the Spirit.” (2 Corinthians 3:18)

By writing his Gospel, St. Luke became another little Christ, accepting God’s grace so fully in his life. The most prolific writer of the New Testament, Luke nourished the Christian flock across the world and across time bringing the Logos’ presence into countless hearts.

The illumination is a powerful reminder of the mystical power of Scripture. As Luke wrote: “Were not our hearts burning [within us] while he spoke to us on the way and opened the scriptures to us?” (Luke 24:32)

Garrison, Eliza. (2017) Ottonian Imperial Art and Portraiture: The Artistic Patronage of Otto III and Henry II, p. 72

Dei Verbum, 21

A’ Lapide, Cornelius. The Great Commentary of Cornelius A’ Lapide Upon the Gospel of Luke, Translated T. W. Mossman (2012)

Notably, none of the other evangelists in this book are pictured with this greenery.

“I looked, and I saw a windstorm coming out of the north—an immense cloud with flashing lightning and surrounded by brilliant light. The center of the fire looked like glowing metal,and in the fire was what looked like four living creatures. In appearance their form was human,but each of them had four faces and four wings. Their legs were straight; their feet were like those of a calf and gleamed like burnished bronze. Under their wings on their four sides they had human hands. All four of them had faces and wings, and the wings of one touched the wings of another. Each one went straight ahead; they did not turn as they moved. Their faces looked like this: Each of the four had the face of a human being, and on the right side each had the face of a lion, and on the left the face of an ox; each also had the face of an eagle.” (Ezekiel 1:4-10)

Revelation 4:6-8

James, Liz. (1991) Colour And The Byzantine Rainbow, 79-80

Otto II was married to a Byzantine Princess so there was a good degree of connection between the Ottonian Empire and Byzantium.

What an awesome illumination and enjoyable read! Very interesting points regarding St. Luke being placed in the mandorla. I love the investigation into such mysterious symbolism that you do. I had never heard of the Ottonian Renaissance before but would love to learn more about that time. It just goes to show you how terms like “Middle Ages” or “Medieval” or especially “Dark Ages” are such misnomers for widely disparate and dynamic cultural periods.

And Amelia I also learn reading from your saints days and you help me pray