The Latin American Baroque is a highly underrated school of sacred art. If you have read a ‘Story of Art’ book, it’s unlikely it was ever mentioned, even though it is the most impressive Christian art movement to come out of the Americas.1

Although I studied Baroque art in college, I didn’t learn about the Viceregal Baroque until I moved to San Antonio in 2017. When I moved, the city was celebrating its 300th anniversary and multiple art museums hosted excellent exhibits on the art of Viceregal Spain featuring liturgical arts of exquisite craftsmanship and many paintings. Although I had briefly encountered this style before, seeing these paintings in the context of San Antonio’s heritage was a quite different experience.

Saint Joseph looms large in the Viceregal Barouque. He was of enormous importance in the new world. Peru, Canada, and Mexico all entrusted their countries to his patronage. The Franciscans declared him the patron of their missionary travels as did the Jesuits. Canada, Texas, California, Brazil and Mexico all have missions named for the saint.2

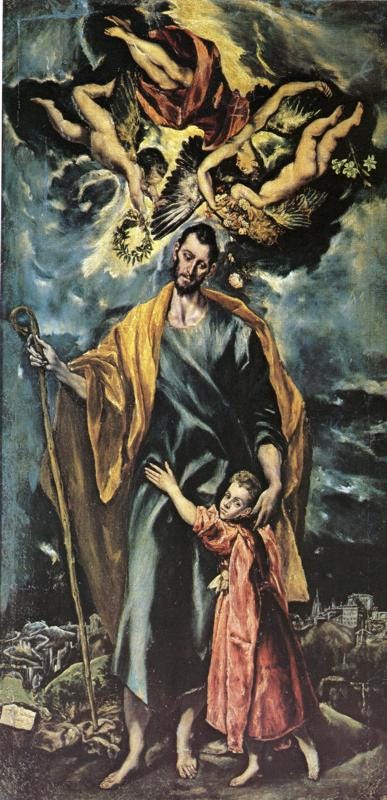

In his book on art after Trent, Emile Mal credits Saint Teresa of Avila (1515-1582), the Carmelite mystic, for spreading devotion to Saint Joseph in Spain and the Americas.3 She dedicated 12 of the 17 convents she founded to Saint Joseph, and her friend and fellow Carmelite, Fr. Jeronimo Gracian, wrote the popular book, The Summary of the Excellencies of Saint Joseph, also called the Josephina, which also helped spread devotion to the saint. Although Spanish painters such as Murillo and El Greco painted the saint, it was in Viceregal Spain where the art of Saint Joseph truly flourished.

The Cuzco school, which grew out of the guilds set up by European painters in Peru, is especially notable. In the workshops of Cuzco, European and Indigenous artists alike studied Flemish and Spanish art as well as Byzantine icons. Eventually, the indigenous artists broke away from the European school, and developed a style distinct from European naturalism. This style is characterized by bright colors, paradisal landscapes, flat figures, religious subjects and abundant use of gold leaf.4 While the religious postures and faces still bear European influence, the elaborate gold details actually accentuate theological themes and motifs. Eventually, overproduction of devotional paintings caused compromises in quality; however, there are still many excellent paintings from the school.

Often, complaints directed towards this style are similar to complaints you may hear about medieval art: the characters are crudely painted; there’s no perspective; the poses are strange etc. Although in many ways, Viceregal art is very different from medieval art, there is a common emphasis on craftsmanship and goldwork. Like medieval artists, the Viceregal artists thought of themselves as craftsmen and mostly remained anonymous. Both styles bring attention to spiritual realities and eschew rigid naturalism or realism. The stock figures may appear crude; however, the detailed craftsmanship and attention to theological detail is masterful. While sometimes playful, the art is also didactic and meant to catechize as much as to delight or inspire.

The Joseph you encounter in the paintings below may be quite different from boring statues of the saint you have probably encountered over the years. In the Latin American Baroque, Joseph is regal and confident, a gentle protector, a strong leader, and a loving father.

This genre of Joseph paintings was popular in Baroque Spain, and exploded in the Americas. Often Joseph is depicted holding Christ or leading him by the hand. The theme is most likely based on a description from Saint Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153),

To Joseph it was given to behold him whom many kings and prophets had desired to see and had not seen, to hear and had not heard. And not only was he allowed to behold him and listen to his words, but he might bear Jesus in his arms, guide his steps, embrace and caress him, feed and protect him.5

These images also emphasize Joseph’s role as Nutritor Domini, the Gaurdian of the Lord. Scenes of the escape to Egypt, which similarly emphasize Joseph’s role as protector and leader of the Holy Family, are also common in this school.6

Palm trees frequently grow in the background of these landscapes, reminding us of Psalm 92:13, the introit antiphon for Joseph’s feast: "The just man shall flourish like the palm tree." The paintings recall the Holy Family’s role in restoring Paradise and invite the faithful to contemplate their own role in this restoration. As Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153) said in a homily,

Therefore, let Mary and Joseph and the Infant be always found in us, that we may live soberly and justly and piously in the world. For it is for this purpose that the grace of God our Savior has appeared instructing us.

In this popular image from the Cuzco school, Joseph and Jesus appear almost as if they are floating before us, hovering on a Paradisal mountaintop. The lack of perspective and the flatness of their bodies project the figures into our space, making their kindly stares all the more direct.

Joseph leads the Christ child confidently on, holding a lily stalk, a symbol of his purity and an allusion to his chaste marriage with the Virgin. Halos burst forth from their hair as rays from the sun. The Incas believed the Sapa Inca was the son of the sun God, and so Christian art in Peru emphasized Christ’s role as the Light of the World. Although Joseph is leading Christ along the path, it is Christ who wears the red sandals, the royal sandals worn by Incan nobility.

Jesus also holds a basket of his father’s carpentry tools, reminding us of the many hours he would have spent under his foster father’s instruction and guidance. In paintings from this period, Joseph and Jesus are often connected in looks and dress to emphasize their similarities in character and in mannerisms.7

Joseph’s regal robes billow down and drape over his body as they drape over the statues in Latin American churches.8 In European iconography, Joseph’s clothing are often muted compared to other figures, emphasizing his humility, but here, he wears Cumbi cloth, the fine wool robes reserved exclusively for Incan royalty. These elaborate robes, decorated with gold leaf patterns, are also meant to connect this New Testement Saint with his royal Davidic lineage. The fact that Christ wears the same robes as Joseph reminds us, as Matthew does, that Jesus inherits his royal lineage from his foster father as well as his mother.

Centuries before Joseph was pictured in this way, theologians had emphasized this connection, calling Joseph the last of the patriarchs. Bernard of Clairvaux highlighted Saint Joseph’s connection to Joseph the Patriarch:

What are we to think of the dignity of Joseph, who deserved to be called and to be regarded as the father of our Savior? We may draw a parallel between him and the great Patriarch. As the first Joseph was by the envy of his brothers sold and sent into Egypt, the second Joseph fled into Egypt with Christ to escape the envy of Herod. The chaste Patriarch remained faithful to his master, despite the evil suggestions of his mistress. St. Joseph, recognizing in his wife the Virgin Mother of his Lord, guarded her with the utmost fidelity and chastity.

To the Joseph of old was given interpretation of dreams, to the new Joseph a share in the heavenly secrets. His predecessor kept a store of corn, not for himself, but for the whole nation; our Joseph received the Living Bread from heaven, that he might preserve it for his own salvation and that of all the world.

A good and faithful servant was the Joseph to whom Mary, the Mother of the Savior, was espoused; a faithful and prudent servant whom our Lord chose for the comfort of his Mother and the nurse of his own childhood, as well as the only and most trustworthy cooperator in the Divine design.9

Thus, Latin American artists bring Joseph’s noble lineage to the fore in a way that had not been done before in art. The resplendent clothing Joseph wears in these paintings does not merely point to his lineage, but also to his noble character. His example is a shining light, especially to families who look to him as a protector and a model.

Paintings of Joseph with Jesus and of the Holy Family were popular commissions for households, intended to inspire families to persue virtue and sanctity in their domestic life. This painting in particular probably hung in a bedroom, inspiring fathers and families to turn to Joseph. As Gracian exhorted, quoting from Genesis, “Ite ad Joseph,” “Go to Joseph.”

Indeed, this painting inspires us to do so.

For more see the Liturgical Arts Journal’s series on Latin American churches:

https://www.liturgicalartsjournal.com/2022/06/churches-of-latin-america-catedral.html?m=1

https://www.liturgicalartsjournal.com/2022/04/churches-of-latin-america-basilica-y.html?m=1

https://www.liturgicalartsjournal.com/2023/08/churches-of-latin-america-basilica.html?m=1

https://www.liturgicalartsjournal.com/2022/05/churches-of-latin-america-sao-francisco.html?m=1

https://www.liturgicalartsjournal.com/2022/05/churches-of-latin-america-sao-francisco.html?m=1

Sandra Miesel: https://www.catholicculture.org/culture/library/view.cfm?recnum=4464

Emile Male, Lart religieux de la fin du XVle siécle, da XVIle siècle et du XVIlle siècle: Etude sur l'iconographie aprés le Concile de Trent, 2nd ed. (Paris Librarie Armand Collin) 1951; p. 315

Elizabeth Lev: https://www.sacredarchitecture.org/articles/the_cuzco_school

Bernard of Clairvaux, Laudes Mariae, p. 13-16

https://archive.org/details/magnificathomili0000unse

Carolyn C. Wilson, “The Image of Saint Joseph in a Selection of Colonial Paintings in Bolivian Collections.” In The Art of Painting in Colonial Bolivia/El arte de la pintura en Bolivia colonial, edited by Suzanne L. Stratton-Pruitt, 155-187. Philadelphia: Saint Joseph’s University Press, 2017

This is something Gracian writes about in his Josephina.

Elizabeth Lev: https://www.sacredarchitecture.org/articles/the_cuzco_school

Bernard of Clairvaux, Laudes Mariae; p. 29

I love, love, love this art form.

I finally got myself a long-desired painting of the Madonna and Child. To me, the handmade frame is an integral part of the work. The whole thing is just exactly what I love: over-the-top gold and decoration, but in a down-to-earth, humble way.

Thank you for all the details in this post! It is indeed an underrated genre!

Thank you for bringing this to light! This art is the highest order of the form we might otherwise call “folk art”. There is much to admire in the humble and direct way the artists portrayed St. Joseph and the Holy Family with such regal fullness. While the images may lack academic style, the sophisticated mind should stumble if tempted to call it primitive art. The description you note from St. Bernard of Clairvaux must be the inspiration for the Prayer to St. Joseph in my St. Joseph Continuous Sunday Missal. The prayer says it as: “O Blessed Joseph, happy man, to whom it was given not only to see and hear that God Whom many kings longed to see and saw not, to hear and heard not; but also to carry Him in your arms, to embrace Him, to clothe Him and to guard and defend Him.” St. Joseph, pray for us.