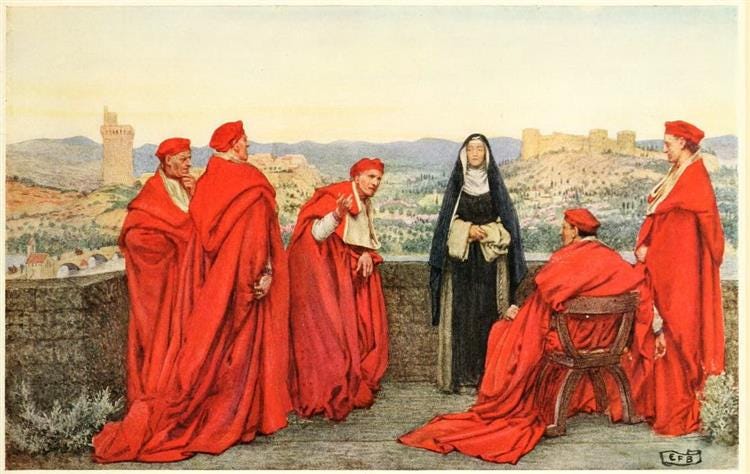

Saint Catherine of Sienna, the Pope, and the Cardinals

A painting by Eleanor Brickdale-Fortescue

It seems fitting that the Church celebrates the patroness of Rome as cardinals prepare for the papal conclave next week. Saint Catherine of Sienna interceded for the papacy once, and this week we can pray she does so again. Her feast day is celebrated on April 29th in the 1969 calendar and April 30th in the traditional calendar.

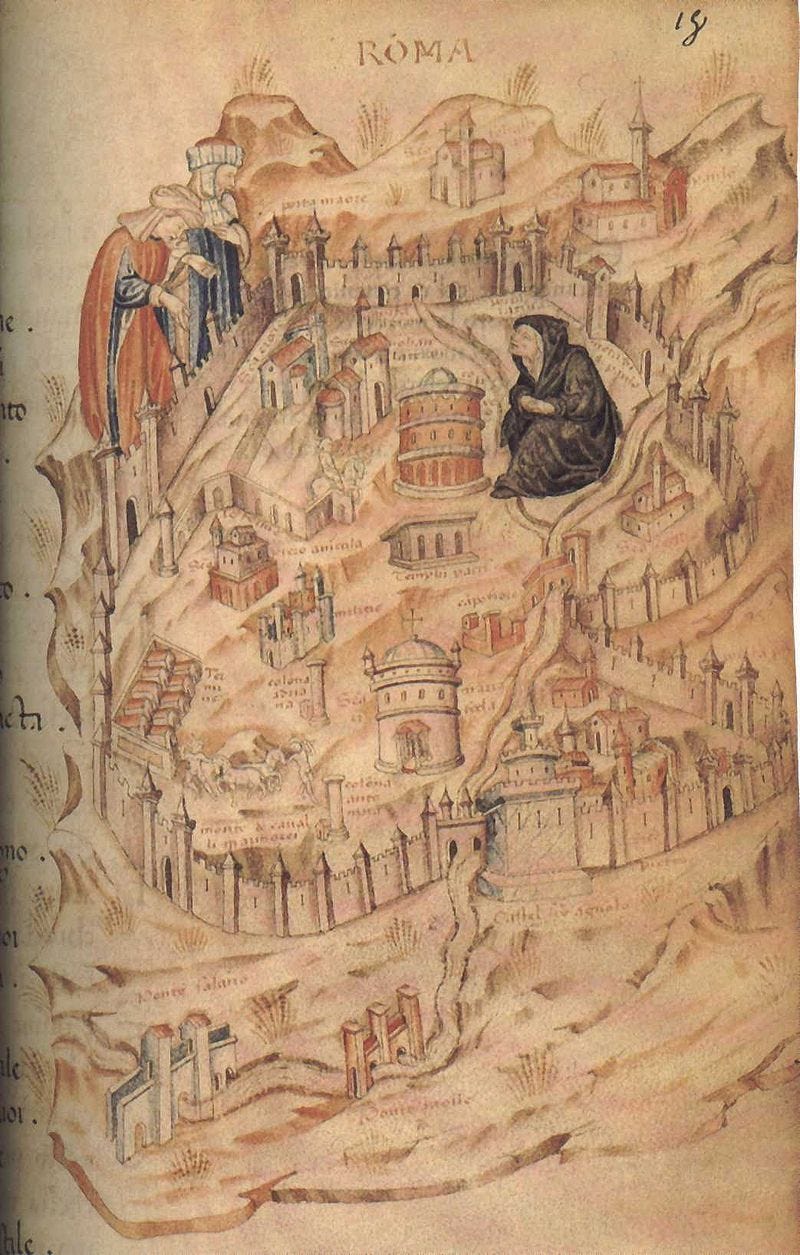

Saint Catherine is now most remembered for her efforts to convince Pope Gregory XI to move back to Rome after the 67-year “Babylonian Captivity,” the period when popes lived in Avignon. During her short life of 33 years, Saint Catherine wrote many letters to cardinals, popes, and clerics urging them to govern with virtue and to live up to the high office entrusted to them.

In her letters, Catherine spoke to Pope Gregory XI with deference and charity to be sure, but also with great candor. She even rebuked him at times, urging him to “be manly and go!” These letters, to Gregory and other clergy and rulers, reveal a woman of great faith, courage, and conviction. Saint Catherine firmly believed that the popes had taken the Church in terrible direction when they fled Rome for the comfort of French palaces. She persistently wrote Pope Gregory XI telling him to return.

I have prayed, and shall pray, sweet and good Jesus that He free you from all servile fear, and that holy fear alone remain. May ardor of charity be in you, in such wise as shall prevent you from hearing the voice of incarnate demons, and heeding the counsel of perverse counselors, settled in self-love, who, as I understand, want to alarm you, so as to prevent your return, saying, “You will die.” Up, father, like a man! For I tell you that you have no need to fear. You ought to come; come then!1

For the love of Christ and his Church, Catherine rebuked the corrupt and encouraged the weak to to be more zealous in the faith. Still, Catherine’s life can not be summarized in a tidy “girl boss narrative.” She was a mystic virgin with intense devotion to the Eucharist and a stigmatist. She had visions, a mystical marriage with Christ, and she levitated. Her most important work, “The Dialogues,” are drawn from her visions and her mystic conversations with God.

Today, I am going to reflect on a painting by the English painter, Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale (1872-1945), a devout Christian who became known as “the last of the Pre-Raphaelites.” Like the Pre-Raphaelites, she painted with vibrant colors and was influenced by the works of the Old Masters as well as Ruskin (1819-1900). Her painting of Catherine is one of her many religious works. Others include stained glass for over twenty churches, altarpieces, and various illustrations for books about the saints.

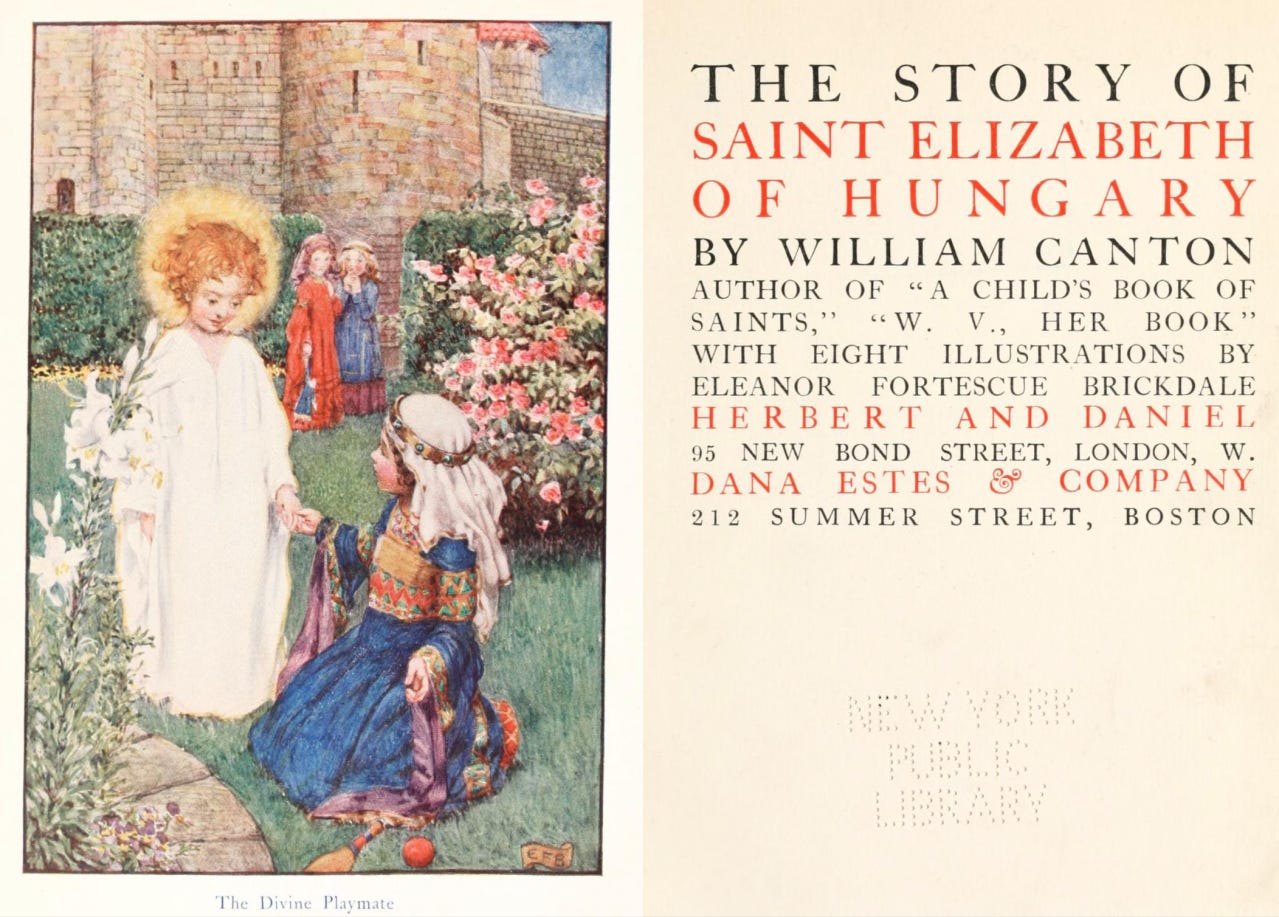

During her lifetime, Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale was best known for her watercolors and illustrations; she illustrated books of poetry, horticulture, and children’s books.

This painting, which was illustrated for the book “Great Women of History,” is titled “Catherine negotiating with Pope Gregory XI on behalf of the Florentines.” At first, I believed the popular title may be erroneous because I didn’t think it looked like the pope was in the painting at all. I thought the illustration depicted Catherine negotiating with the Florentine cardinals, urging them follow Gregory back to Rome.

However, after confirming that the popular title is indeed the way Brickdale labeled the painting in her book, I think my initial assessment was probably wrong. It would be strange if the artist herself mislabeled her own painting.

At first glance, I still think the pope can be hard to find. He is seated inconspicuously, and his clothing blends in with that of other cardinals. It is not unusual for the pope to wear red as the cardinals do, but it is strange that his clothing does not stand out from the cardinals. I think Brickdale may have painted the pope inconspicuously to highlight the way he shrank away from the responsibilities of his office when he remained in Avignon. While the Popes lived in Avignon, respect for the papacy waned, and regional factions of cardinals went rogue.

Although the pope blends in with the cardinals in some ways, he stands out in others. Most obviously, he is seated. He also looks collected in a way that the other cardinals are not and seems to give Catherine the respectful attention no other cardinals in the painting do.

Ultimately, Gregory listened to Catherine and mustered the courage to move back to Rome.

Like the cardinals in the painting, we are drawn to Catherine, who appears to possess a gravitas based upon her faith and moral authority. She stands tall as she is unwavering in her mission. Her upright posture matches the upright character of her life, and she embodies the virtues her habit symbolizes, purity (white) and humility (black). Her sideward glance may reveal what she thinks about the cardinal beside her who appears to be talking.

Catherine’s bold words held weight with the pope and clergy because she lived with remarkable integrity. Unlike the cardinals who fled their responsibilities in Rome for a life of comfort in Avignon, she did not succumb to the charms of the world. Catherine lived as a habited Dominican layperson, and spent much of her time in prayer and with the sick, whom she tended to during the plague. She also counseled prisoners and accompanied them up to the moment of death. Her life is a story of the corporal and spiritual works of mercy.

In the painting, Catherine stands apart from the cardinals with an air of quiet dignity, her hands folded. Her simple black robes contrast with the vibrant scarlet robes of the cardinals.

Cardinals wear red robes for good reason. The red represents the blood of the martyrs, who shed their blood for love of Christ. It is supposed to remind cardinals that they must be willing to die for the faith. Yet, by looking at this image, we know the cardinals surrounding Catherine do not possess the same courage as their predecessors. Their own luxury and cowardice have stained the dignity of their robes.

These men are intrigued by the saint’s presence and seem to even respect her; however, their contorted positions and quizzical glares reveal their uncertainty and hint at their less-than-upright characters. We also know from history that corruption ran rampant among the Church’s hierarchy in this period.

Despite the turbulence of her time, Catherine did not give into despair, but continued to pray and write letters urging reform. In one letter, she cautioned the pope to beware clergy who love their own reputation more than their flock:

They see the infernal wolves carrying off their charges and it seems they don't care. Their care has been absorbed in piling up worldly pleasures and enjoyment, approval and praise. And all this comes from their selfish love for themselves. For if they loved themselves for God instead of selfishly, they would be concerned only about God's honor and not their own, for their neighbors' good and not their own self indulgence. Ah, my dear babbo, see that you attend to these things! Look for good virtuous men, and put them in charge of the little sheep. Such men will feed in the mystic body of holy Church not as wolves but as lambs. It will be for our good and for your peace and consolation, and they will help you to carry the great burdens I know are yours.2

With Catherine, we must pray that the future Pope is a man of wisdom, faith, and virtue and that he dares to stand up to wolves in his midst, disciplining the corrupt and appointing wise and holy men to be his advisors and bishops.

A few other books illustrated by Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale:

https://where-you-are.net/ebooks/catherine-of-siena-seen-in-her-catherine-of-siena.pdf

https://medieval.ucdavis.edu/20C/Catherine.html

Saint Catherine of Sienna, pray for us! ⛪🌐✝️

Wow! The observations about the cardinals apply perfectly to some of today’s cardinals. Cardinal Zen is a St. Catherine of Siena man though.