Millais, Catholicism, and the Victorian Critics

On why the Victorian critics hated this painting

In the Catholic Church, the month of February is devoted to the Holy Family. As of last Sunday, Septuagesima, we are also now preparing for Lent1. Christ in the House of His Parents by Sir John Everett Millais provides a fitting meditation for the season, as it offers a rich meditation on the Holy Family while also pointing to Christ’s Passion.

Today I am going to explore the notoriously critical response to this painting. I think it is worthwhile to address, in large part, because the anti-Catholic caricatures of these Victorian critics still shape popular narratives about the Middle Ages and medieval art. Due to the length of the initial post, I have split it up in to two parts and will explore the rich symbolism and meaning behind this work in part two, which I will post next week.

Although this beloved painting was initially panned by critics, it is now widely considered a Pre-Raphaelite masterpiece. I was able to see it a couple of years ago when I visited London, and seeing it in person exceeded my expectations. The elaborate gold frame gives the earthy scene a kind of heavenly perspective. The original title from Zachariah 3:6 read: “If someone asks, ‘What are these wounds on your body they will answer, ‘The wounds I was given at the house of my friends.’”

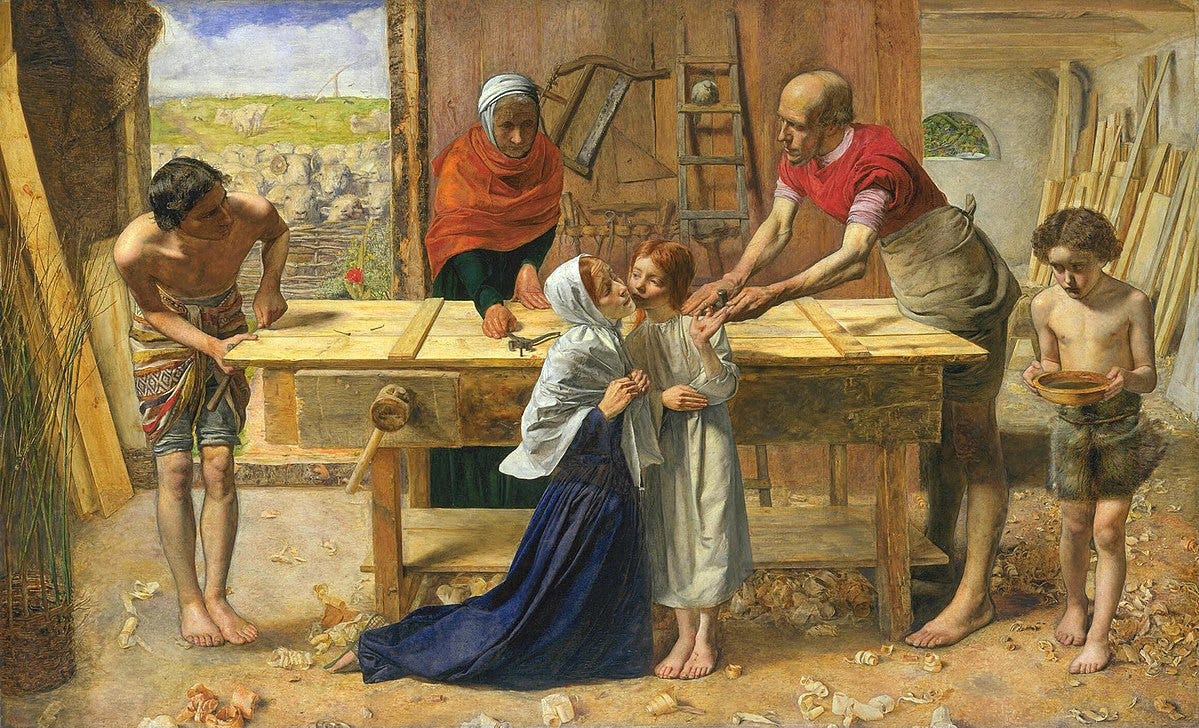

Inspired by a Tractarian sermon, Millais painted an image of the Christ child, wounded by a nail in Joseph’s workshop. The blood from the wound has stained the table behind him and dropped onto his foot. Mary kneels beside him as if to console him. Joseph looks at his hand, as if to contemplate the wound. John the Baptist serves his cousin by bringing water to wash his wound, and Christ’s grandmother Anne pries the nail from the door. A flock of sheep look on eagerly from behind the fence.

Ancient Christian symbols from medieval iconography abound, enriching the painting with meaning. For example, the instruments of Christ’s passion hang on the back wall. Although the workshop is humble, it does not appear dingy, in my opinion. Even the wood curlings seem to have a glow to them, and the figures have been beautifully and harmoniously arranged to frame Christ. The symmetrical nature of painting highlights Christ’s centrality. He ties the painting together, as all of the figures and symbols point back to him and to his Passion, which is prefigured by the wound he holds before us.

So why was this painting so fiercely and viciously attacked by Victorian art critics? A quick internet search will tell you that the critics disliked the painting because of the way Millais depicted the poor circumstances of the Holy Family. Charles Dickens famously hated it saying that Jesus looked like a "wry-necked, blubbering red-headed boy in a bed-gown, who appears to have received a poke... playing in an adjacent gutter.”2

So, from this search you may come away with the conclusion that the critics were scandalized by the poverty of the Holy Family. While partially true, this is not exactly an accurate picture of the reviews. Millais’ attention to naturalistic detail was controversial; however, the critics balked most at the way Millais incorporated medieval techniques and Catholic symbols into his painting.

As one critic for the Spectator wrote of Millais:

A painter who can spontaneously go back not to the perfect schools (Renaissance) but through and beyond them to the days of puerile crudity (Middle Ages) seems likely to be conscious of some fatal constitutional disease3

When the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood formed in 1848, with the intention to return to the simplicity and purity of the Gothic painters, they referred to themselves in public as “PRB.” Shortly before Christ in the House of his Parents was exhibited in 1850, the name of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood leaked to the public. The sensational reaction to Millais’ painting was largely a reaction to the leaked name of the group.

This name proved controversial because of its Catholic associations. In fact, it "was generally ... believed by most of the journalists (c.1850) that the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was a hidden and subversive form of Roman Catholic propaganda.”4 Medieval art, which had been labeled “primitive” was associated with Catholicism, and English society at this time was solidly anti-Catholic, also recently on edge after the Pope had recently reinstalled a hierarchy of English Bishops in 1850, the same year this painting exhibited.5

While privately Millais expressed admiration and sympathy for Catholics, he never converted. During the late 1840s, he and and a couple of other Pre-Raphaelite painters did attend an Anglican Tractarian church in Oxford, a church which many saw as being dangerously close to Rome.6 Unlike most Anglicans at the time, the Tractarians emphasized the sacrificial element of the Eucharistic, and sought to revive Catholic religious traditions which had been suppressed after the Reformation.

Indeed, one of the most prominent Tractarians, John Henry Newman, did convert to Catholicism in 1845. Close to the end of his life, Millais painted the Saint. According to Newman, “Mr Millais thinks his portrait the best he has done and the one he wishes to go down to posterity by.”

When Millais painted Christ in the House of his Parents in 1850, the Royal Academy, though losing popularity, still reigned in the English art world. The Academy was committed to Neo-Classical idealism and taught that the medieval style was primitive and simplistic. In this understanding, the Raphaelites and the Protestant Reformation were both progressive movements which helped society move away from Catholic “superstition.”

Charles Dickens spends most of his review mocking the medieval connection in Brotherhood’s name, equating the group of painters with other hypothetical retrogressive groups such as the “Pre-Newtonian Brotherhood,” “the Pre-Copernican Brotherhood,” “pre-Galileo Brotherhood,” “pre Henry VII brotherhood.” He goes on to say that these artists threatened

cancelling the advances of nearly four hundred years and reverting to one of the most disagreeable periods of English History, when the Nation was yet very slowly emerging from barbarism…As the time of ugly religious caricatures called mysteries, it is thoroughly Pre-Raphael in its spirit.”

Finally, he warned that, “We should be certain of the Plague among many other advantages, if this Brotherhood were properly encouraged.”7

One seemingly bizarre element of the reviews are the elaborate descriptions of diseases critics presume Millais has painted into this picture. These gross descriptions matched exactly with the exaggerated cartoons of the Irish poor which were common in newspapers and penny dreadfuls at the time.8 9Dickens even made this Catholic association explicit when he complained that Saint Joseph and his apprentice looked like “dirty drunkards” whose "very toes had walked out of St. Giles's (the Catholic parish also called little Ireland)”

The Tait critic complained that Christ looked like an "unwashed, whining brat, scratching itself against rusty nails in a carpenter's shop in the Seven Dials (another poor Catholic parish.)”10 In reality, Millais had not pulled models out of the slums but had used an actual carpenter as a model for Joseph, his sister-in-law as a model for Mary, and his nephew as model for Christ.

One critic from the Examiner claimed that the figures in this painting represent the “filthy squalor affected by ascetics of the darkest middle ages; when a female devotee was canonized for wearing dirty petticoats, and for encouraging vermin to nestle in her locks.” 11Thus, these critics associated medieval era, the age of faith, with everything they despised about the Irish Catholics living in the slums of London—poverty, superstition, and disease.

This idea that medieval art was primitive and had to “evolve” in order to reach perfection in the art of Raphael is a flawed Anti-Catholic caricature. Although this narrative has been debunked, the “Whig history of art,” as

so aptly calls it, dominates art history textbooks, even ones used by Catholic schools.

She explains,

It (the Whig narrative) assumes that history is a steady march toward improvement, willed by the cosmos, toward something greater and more enlightened. As with the simplistic story of human evolution, this approach leaves a lot out, glossing over the multi-layered complexity, specific cultural developments and achievements, and most of all spiritual value of earlier forms of art, particularly Christian sacred art.12

After the critical reaction to the painting, three artists left the group and most in the group abandoned their “medievalism” and many their religion altogether.13

It’s hard to blame him after he received threats like this one:

Millais may take his choice between fine and imprisonment, and a dark room and a keeper. His picture is conclusive evidence against him, either on an indictment for blasphemy, or a writ de lunatico inquirendo.14

To my knowledge, not one review actually mentioned the central theme of Millais’ painting, although the Tait critic hints at it actually being the problem:

The fault of the mediævalists certainly is not a want of confidence in their own peculiar belief. They are the enthusiasts of retrogression, and, like other enthusiasts, they glory in martyrdom.15

The Victorians accepted the “gothic revival” insofar as it was neutered from its Catholic roots. Although the famous Catholic architect Augustus Pugin revived many Churches, in large part the Victorian medieval revival centered around secular buildings and romantic narratives.

To the critics’ horror, Millais had not only brought back aesthetic qualities of medieval art, he had also resurrected the sacred aesthetic cannon which illustrated theological truths of the Church. This painting stood in contradiction to a common Victorian idea that Christianity was merely a moralizing and civilizing force. By pointing to Christ’s Passion, in such a central way, Millais challenged core notions of respectable Victorian religion. The painting reminds us that the Cross is the center of the Christian faith, and the event through which everything else comes into focus.

In part two, I will reflect on the painting itself and its rich symbolism.

Thank you for sticking around during my substack hiatus this past month. Writing took a backseat as we navigated multiple bouts of illness and a job transition for my husband. Lord willing and the creek doesn’t rise, I should be back to writing weekly posts.

God Bless,

Amelia

On Septuagesima see: https://www.newliturgicalmovement.org/2021/02/septuagesima-time-that-land-forgot.html?m=1

See p. 5-13 of the PDF for Dickens’ full review: https://www.forgottenbooks.com/en/download/OldLampsforNewOnes_10097486.pdf

Dickens is certainly one of the greatest novelists of all time; however, his art criticism is riddled with anti-Catholic caricatures which were so common during his day.

“The Royal Exhibition,” The Spectator 1850-05-04: Vol 23 Iss 1140, p. 427

https://archive.org/details/sim_spectator-uk_1850-05-04_23_1140/page/427/mode/1up?q=millais

Bentley, D. M. R. “The Pre-Raphaelites and the Oxford Movement.” Dalhousie Review, vol. 57, no. 3, Fall 1977, pp. 531

This act, which Victorians called “papal aggression,” was widely protested.

Although this association was short-lived, it is well documented. See:

Bentley, D. M. R. “The Pre-Raphaelites and the Oxford Movement.” Dalhousie Review, vol. 57, no. 3, Fall 1977, pp. 531-532

Dickens, p. 12

Paz, D. G. “Anti-Catholicism, Anti-Irish Stereotyping, and Anti-Celtic Racism in Mid-Victorian Working-Class Periodicals.” Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies 18, no. 4 (1986): 601–16. https://doi.org/10.2307/4050132.

“Their emaciated bodies, their shrunken legs, and tumid ancles, are the well-known characteristics of that morbid state of system. The incipient dema of the lower extremities is faithfully portrayed; though in connection with this symptom, which indicates far-gone disease, the abdominal tension might have been more strongly marked. The boy, advancing with the bowl of water, exemplifies a splendid case of rhachitis, or rickets; and the osteological distortions of his frame have been correctly copied from the skeleton. The child in the centre is expressively represented with the red hair, light eyebrows, and mottled complexion, which betoken the extreme of struma. The female figure kissing it, apparently its mother, is endowed by the artist with the same peculiarities, in accordance with the laws of hereditary transmission. With a nice discernment, too, the squalid filth for which the whole group is remarkable, is associated with a disorder notoriously connected with dirt.” from "Pathological Exhibition at the Royal Academy (Noticed by our Surgical Advisor)," Punch May 19, 1850, 198

"The Royal Academy: May Exhibition," Tait's Edinburgh Magazine, vol. 17 (June 1850), p. 356

https://archive.org/details/sim_taits-edinburgh-magazine_1850-06_17_198/page/357/mode/1up

“Fine Arts,” The Examiner 1850-05-25: Volume None, Issue 2208, p. 326

https://archive.org/details/sim_examiner-a-weekly-paper-on-politics-literature-music_1850-05-25_2208/page/325/mode/1up

Early in their careers, the Pre-Raphealites were very close to the Anglo-Catholic couple at Oxford, the Combes. Later, they fell under Ruskin’s influence. Ruskin encouraged their interest in detailed naturalism but discouraged their religious sentiments.

William Holman Hunt was a devout Protestant and is famous for his religious paintings. His religious art was more accepted than the other Pre-Raphaelites because the symbols he used were more explicitly Protestant.

Tait, p. 356

Tait, p.356

Terrific analysis! Great essay.

Ah, Dickens! I knew he was anti-Catholic, but this post really points out his animosity. As always, this post about Millais is fascinating and well-researched. I was really interested in this painting because I didn't realized it preceded Ophelia. This certainly is a painting I'd love to see in person.