"This is the Rule and Life of the Friars Minor, namely, to observe the Holy Gospel of Our Lord Jesus Christ, living in obedience, in poverty, and in chastity." -St. Francis of Assisi, Rule of St. Francis.

In popular culture, Saint Francis is sometimes imagined as a persecuted revolutionary or a hippie who strove to remake the hierarchical church into an egalitarian community. These fictitious fantasies could not be further from the image painted by his own letters or by his contemporaries.

It is true that Francis strove to reform rampant corruption within the church. He also influenced art and theology in a singular way;1 however, he was very much formed and embraced by the medieval church. In fact, he was so well-loved by the laymen and hierarchy alike that Pope Gregory IX canonized him in 1228 AD, just two years after his death.2 Two days after the canonization, the pope laid the first stone at what would become the Basilica of Saint Francis in Assisi.

Immediately, artists flocked to paint the walls of the basilica dedicated to this beloved Italian saint in a new style inspired by Francis’s meditative emphasis on the life of Christ in the Gospels. One such artist was Giotto Bondone, a painter known for his expressive figures and lyrical storytelling.

Giotto was undeniably devoted to Saint Francis; he joined the Franciscans as a tertiary and even named his children Francesco and Chiara after Saints Francis and Claire. The Franciscan spirit permeates all his work, and it’s telling that his paintings of Francis in Assisi and Florence bookend what is known of his artistic career.3

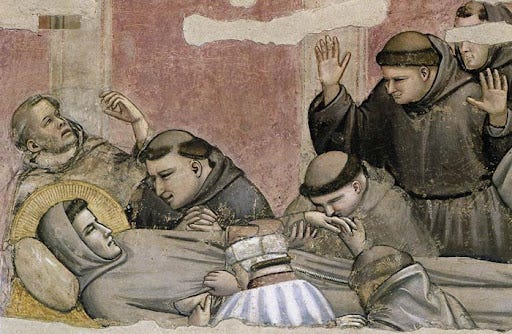

Art historians love to comment on the way Giotto opened the emotional lives of Jesus and the saints in a never before seen way. What’s often neglected in these commentaries is Giotto’s focus on mystic miracles. These miracles confound a merely humanistic reading of the painter. In Giotto’s frescoes, Francis weeps, yes, but he also levitates, rides mystic chariots, and receives the stigmata.

In the frescoes on the lower walls of the upper church, Giotto weaves together the many paradoxes that Francis embodies.4 Here, Francis is both a suffering mystic who receives extraordinary visions and a simple friar who loves to sing with God’s creatures. He lives in austere poverty but exudes love and joy. He enjoys great popularity but also endures suffering and humiliation. He scorns the corruption in the church but retains a profound reverence for priests and the pope.5 He renounces all worldly possessions but insists that priests exclusively use the most precious materials to hold the Body of Christ in the Eucharist. He gains ecclesiastical approval and admiration but cherishes simplicity and spends much of his time in prayerful solitude.

Giotto vividly brings these paradoxes to life.6 By rendering stories from Bonaventure’s Legenda Maior (1253) into frescoes, Giotto helps us see how Francis allowed the Holy Spirit to transform him in such a way that the posture of his life came to resemble that of Christ.

The slope of the architecture and landscape in the first bay, which includes all three scenes, is a visual metaphor for Francis’s journey from repentance to holiness. In this bay, there is a rhythmic falling and rising of the architecture in the background. This is an apt metaphor for the spiritual life where descending is necessary for ascending. These first few scenes, which set the stage for Francis’s conversion, powerfully foreshadow the arc of Francis’s life.

From the outset, Giotto introduces Francis as a saint who walks in the footsteps of Jesus Christ. This first image calls to mind Christ’s entrance into Jerusalem.

In the first scene, a simpleton lays out his cloak for Francis to walk on, predicting that Francis will accomplish great things. Francis hesitantly steps on the cloak, beginning a journey that will lead him away from his worldly life as the wild son of a wealthy merchant. The way Giotto uses space between Francis and the pauper builds a kind of narrative suspense that draws us into the life of the charismatic young man. A prominent temple in Assisi, which was used as a prison in Francis’s day, towers between Francis and the pauper, symbolically representing the way the young Francis is still imprisoned by his ego in this fresco.7

In the fresco pictured above, Francis journeys home after serving time in a neighboring city’s as a prisoner of battle. Here, he stands between two mountains, handing his cloak to an impoverished knight. This spontaneous act of generosity points to the saint’s future commitment to poverty. Removed from the life of the city, he begins to listen to the call of the Spirit. By humbling himself, he begins his walk down the road that will conform him to Christ.

Next, Giotto brings us out of the Umbrian wilderness and into a mystical dream. In the dream, Christ points to an elaborate Gothic armory, showing Francis where to find clothing for his knights. The dream foreshadows Francis’s creation of the Franciscan order, whose friars battled demons, materialism, and corruption in sackcloth habits rather than literal armor.

All three scenes in bay two tell the story Francis’s dramatic conversion. The dilapidated San Damiano chapel in the first image balances and contrasts with the ornate but tilting Lateran chapel in the third; both churches are in a state of disrepair which symbolizes the disrepair in the church.

In the first scene Francis prays before the crucified Christ in the crumbling church. Here, Christ calls on Francis to “repair his house.” At first, Francis interprets this command literally and begins selling his father’s expensive cloth to rebuild the dilapidated church, notably without his father’s consent.

Although he eventually realized the symbolic meaning of this calling, Francis retains a commitment to the physical restoration of churches out of reverence for the Eucharist. 8

This image powerfully recalls Paul’s words and foreshadows the miracle of the stigmata. “I have been crucified with Christ; yet I live; and yet no longer I, but Christ liveth in me: and that life which I now live in the flesh I live in faith, the faith which is in the Son of God, who loved me, and gave himself up for me” (Galatians 2:20).

This fresco is the first of many in which Giotto paints Francis praying before the Crucified Christ.

In the next scene, Francis faces his father, who has summoned him to court for stealing. Francis returns the expensive cloth to his father, dramatically stripping and renouncing all worldly possessions.

Again, Giotto uses space to heighten the emotional impact of Francis's separation from his family and life of old. Giotto presents Francis humiliated and separated from his father and the crowd of Assisi. Yet Francis pays the world no heed; he focuses his gaze on Heaven with his hands held together in prayerful submission. He is embraced by the bishop, and God’s hand descends from Heaven to bless his radical act of conversion.

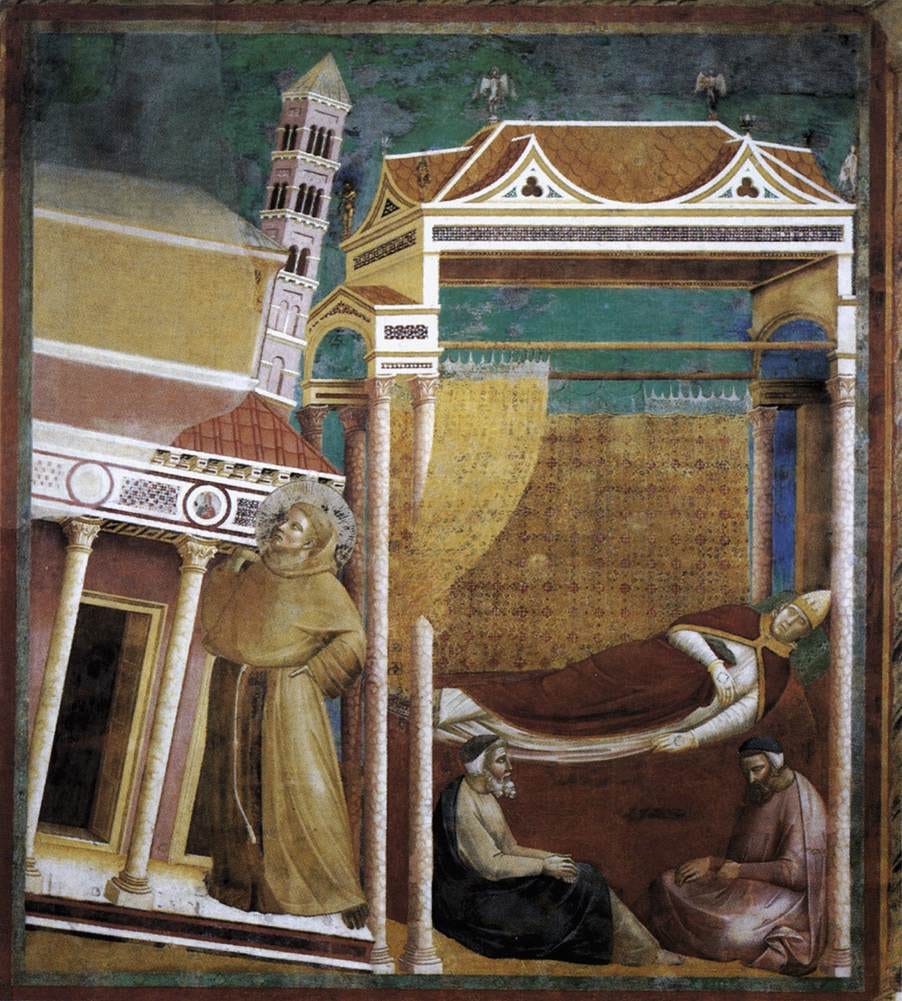

In the last panel, Giotto gives us a glimpse into Pope Innocent's dream of Francis holding up the Church. Filled with the strength of the spirit, Francis stands tall and holds up the weight of the church, which precariously tilts toward the pope.

By living a life of poverty and simplicity, Francis helps others discover the beauty of the life of Christ. The pairing of the two chapels is reminiscent of one of C. S. Lewis’s observations in The Four Loves, “The highest cannot stand without the lowest.”

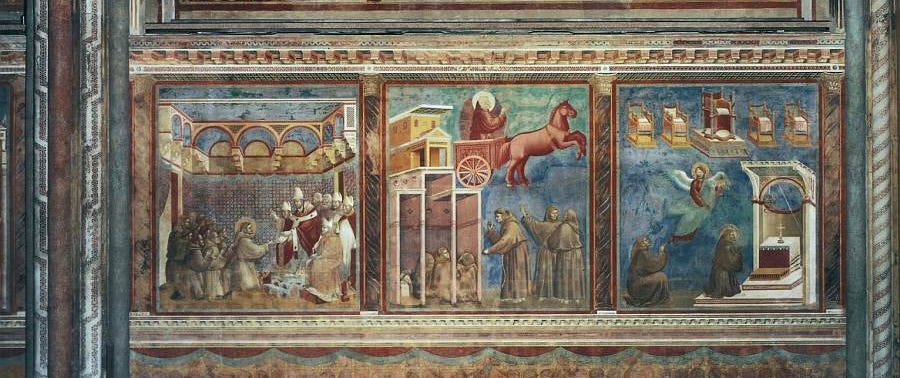

The three scenes in the third bay on the north wall bring us into the early days of the Franciscan order. Architecturally, the arches in the Lateran Basilica from the first scene balance with the vision of thrones in the last scene, showing that the earthly palace is built to be an image of the Heavenly Palace.

The first scene in this bay is set in the same Lateran palace from the pope’s dream. Francis visits the pope joined by his band of 11 friars, unified by their brown habits and prayerful posture. In this scene, Pope Inocent III approves the rule Francis wrote for the order which is based on the life of Christ in the Gospel. The group of tonsured friars contrasts with the finely dressed group of clerics behind the pope; however, Giotto illustrates the seemingly opposed groups relating to each other in harmony. There is room for splendor and poverty within the Church because she is meant to resemble Christ in both his majesty and his humility. Still, Francis’s witness to the Gospel is a prophetic challenge for the complacent clerics. He reminds them that they too are called, as is every Christian, to conform their lives to Christ.

In the following scene, Francis miraculously appears to the friars as a new Prophet Elijah flying on a chariot. While some friars gaze in amazement others sleep inside. Their reactions reveal how they only slowly become aware of the holiness of their founder.

In the third bay's final scene, an angel gives Brother Leo a mystical vision, pointing to the throne that Francis is destined to assume. Meanwhile, Francis focuses his attention on Christ at the altar. Like Christ, the friar retreats to pray after performing miracles. Giotto paints Francis in prayer more than in any other posture.

The last bay of the north wall depicts Francis in his public ministry. In the tenth scene, Francis prays as Brother Sylvester sends the demons out of the city of Arezzo. Once again, Giotto uses architecture to reveal the spiritual truth of a space. He depicts the city as a Babel-like configuration of buildings that precariously crowd and stack on top of each other.

In the next scene, Francis and another friar stand between a Sultan and a group of imams. The imams appear to leave the scene, declining Francis’s challenge to walk into the fire between them. Francis offers to walk into the fire if the Sultan will convert, but the sultan only offers precious gifts to Francis. Francis has no use of earthly possessions and so refuses the Sultan’s offer. The gap between them represents the spiritual chasm between the Sultan’s offer and true conversion.

After this scene, Giotto again shows Francis in prayer. His outstretched arms remind us of Christ on the Cross. The friars are confounded by their leader's mystic experience of suffering and communion with Jesus. Here, we are reminded that Giotto’s Francis does not fit into our modern humanistic framework.

When we confront Francis in the frescoes of Assisi, we must confront the miracles he performed, the demons he faced, and his devotion to Christ’s passion. The miracles are not merely frosting on a humanistic cake, they are the heart of Giotto’s narrative.

The final scene on the north wall depicts the famous nativity crèche Francis erected to help others meditate on the mystery of Jesus’s birth. Amidst a colorful and crowded group of laymen, clerics, and friars, Francis places baby Jesus in a manger, with an ox and ass next to it. By gazing at the jubilant scene, you can almost hear the friars singing.

An altar with a ciborium over it stands behind the crèche, and the Cross marks the top of the scene. Here, Giotto connects the condescension and outpouring of God’s love in the Incarnation to the condescension and outpouring of God’s love on the Cross. The trio of images reminds us that Christ would give his body on the Cross as Heavenly food for us to receive in mass. The baby who rests in the box meant to hold animal food is himself the Bread of Life, the true God.

In part two, we will dive into the frescoes on the south wall which feature the famous scene of Francis preaching to the birds as well as the miracle of the stigmata.

If you would like to get to know Saint Francis better I suggest reading either Bonaventure’s Life of Saint Francis or the Little Flowers of Saint Francis.

I highly recommend the beautiful illustrated edition of the Little Flowers of Saint Francis that

put together from a German edition. It is a great read for almost any age and a good read aloud for children. Find it here or here.David Jeffery has a short section on the Franciscan influence on art in his wonderful book In the Beauty of Holiness: Art and the Bible in Western Culture.

One of the fastest canonizations in all of Church History.

Giotto is most famous for his work in the Arena Chapel where he painted frescoes of the life of Christ.

Jacopo Torriti painted frescoes of scenes from the Old and New Testaments above Giotto’s scenes of Francis. These frescoes enrich the meaning of Giotto’s but unfortunately I don’t have the space in this article to write about the parallels here. Cimabue he also has some beautiful paintings in the church. You can see a 360 view of the upper church here: https://www.sanfrancescopatronoditalia.it/basilica/

“We must be Catholics. We ought to visit churches frequently and venerate clerics, and revere them, not so much for their own sake, for they may be sinners, but on account of their office and administration of the Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ, which they sacrifice on the altar and receive and minister to others.”

This quote is from Francis’s “Letter to Clergy” which I sourced from

’s excellent article on Francis’s devotion to the Eucharist.https://www.newliturgicalmovement.org/2018/09/st-francis-of-assisi-eucharistic-mystic.html

Vasari attributed the frescoes to Giotto, but modern scholars disputed this attribution. Many of the most prominent Giotto scholars, such as Andrew Martindale, have returned to the original assumption that Giotto designed and painted the frescoes.

It’s probably true that Giotto employed a workshop to paint with him; however, the unity of vision within the cycle and the harmony between the paintings make clear Giotto’s principal role in designing the frescoes.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temple_of_Minerva,_Assisi

https://www.ewtn.com/catholicism/library/testament-of-st-francis-5488

“Above everything else, I want this most Holy Sacrament to be honored and venerated and reserved in places which are richly ornamented.”

Great work, Amelia. Very edifying. Have you been to Assisi yourself? I was able to go last October to see these in person. It's remarkable how the context of Assisi itself - the features of the town - fill out the experience. Especially when you see the same buildings in Assisi depicted in some of the works.

I went to Assisi a few years ago and I felt such a sense of wonder that in the middle of a world like ours—with greed, betrayal, fraud —comes Francis with his simplicity, boldness, and awe of God’s reality. Your essay on Giotto’s illustrations was like a little pilgrimage. Thank you.