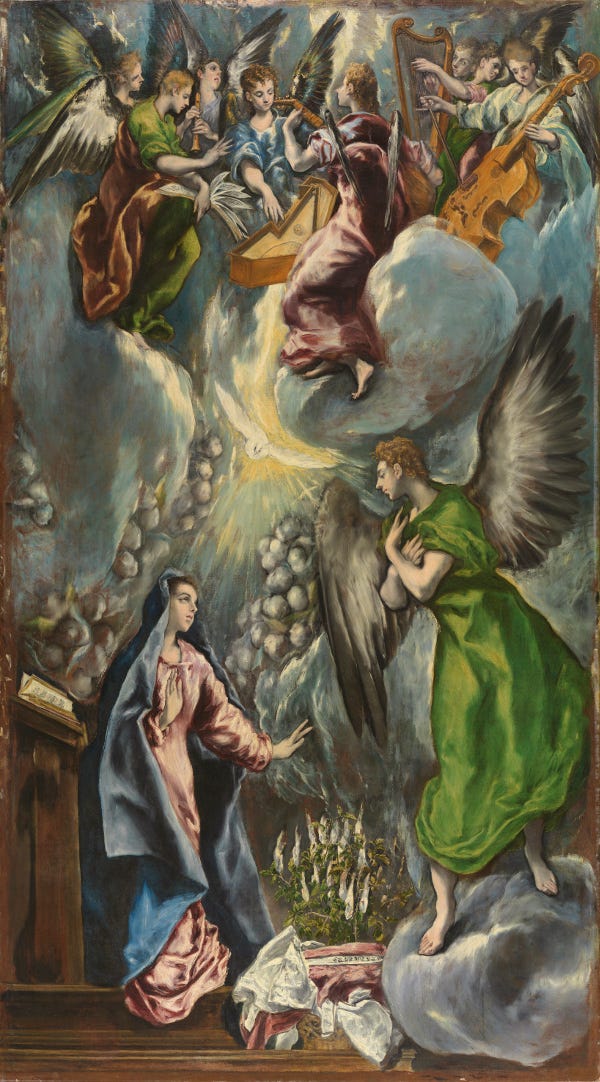

There is no doubt that the artwork of Domenikos Theotokopoulosis is extraordinarily unique. The qualities that make his art so unusual— electric color combinatitions, expressive elongated bodies, and strange perspective— also make it fitting for portraying the transformative presence of the Holy Spirit.

As a teenager, Domenikos studied icons with his father on the island of Crete. He retained this eye for the spiritual throughout his career, traveling throughout Italy and finally to Spain, where he was given the nickname El Greco—Little Greek. In his mature work, El Greco masterfully combines Titian and Tintoretto's ethereal Venetian color scheme with what he learned from his study of Michelangelo's expressive bodies.

Artists have long used the biblical signs of the Holy Ghost—fire, wind, water, and the dove—to visualize the Spirit in art. El Greco incorporates all of these signs into his paintings revealing how the Holy Spirit illuminates, comforts, and fortifies the hearts of the faithful. Indeed, El Greco seems to have been drawn to scenes from the Gospels that explicitly mention the Spirit—the Annunciation, the Baptism of Christ, and Pentecost—painting these scenes often.

El Greco’s style is often called ethereal because of his tendency to elongate figures and combine colors in strange ways; however, the bodies he paints are not Gnostic shadows but unmistakably corporeal. As such, he is able to demonstrate Christ’s divine humanity as well as the presence of the Holy Spirit in the lives of the Saints in a particularly compelling way.

The painting of Pentecost was not meant to stand alone, but was part of a larger altarpiece, which is thought to have included images of the Annunciation, the Adoration of the Shepherds, and the Baptism of Christ on a lower story and images of the Resurrection, the Crucifixion, and Pentecost on the upper story. Commissioned for an Augustinian monastery, these images provide a profound meditation on the life of Christ and the role of the Holy Spirit in the Church.

Pentecost depicts the dramatic scene from the Acts of the Apostles 2:1-4, when the apostles had been praying in Jerusalem for nine days following the Ascension.1

And when the day of Pentecost was fully come, they were all with one accord in one place. And suddenly there came a sound from heaven as of a rushing mighty wind, and it filled all the house where they were sitting. And there appeared unto them cloven tongues like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance.

In the painting, light emanates down from the Holy Spirit, painted as a dove, down to Mary and the apostles below. El Greco paints with large brush strokes to portray the movement of the light's descent to the apostles. This light from the Holy Spirit infuses the entire space and illuminates the faces of Mary, Mary Magdalene, and 13 other apostles. The dark background projects the apostles towards us so that we are confronted by the mystery.

Incandescent colors and elongated bodies topped with tongues of fire seem to rise as if they have become burning torches. The flame-like appearance draws us back to the Holy Spirit, the Eternal Flame, from whom the apostles receive the gifts. Hand gestures also resemble flickers of fire. They blend with the background and point upward, reminding us that the bodies of the apostles have become, as Paul says, temples of the Spirit.

El Greco arranges the three most prominent figures— Mary, Peter, and John— together in a pyramidal scheme. This arrangement gives the painting a sense of order amidst the dramatic intensity of the moment. Mary sits most serenely among the apostles, her hands folded in prayer, while Peter and John fall backward, their hands outstretched in ecstasy. Peter, who stands out in the bright yellow, leads us to Mary, who leads us to God.

Mary usually has a central role in Western images of Pentecost. El Greco largely follows the same iconographic scheme as the image of Pentecost in the sixth-century Rabbula Gospels, where the apostles surround Mary in a domed space topped by the dove representing the Holy Spirit. In the Liturgical Year, Dom Guaranger sheds light on why Mary is featured so prominently in images of Pentecost:

Heretofore, He overshadowed her and made her Mother of the Son of God; now He makes her the Mother of the Christian people…. The Spirit of love here fulfils the intention expressed by our Redeemer when dying on the cross. “Woman!” said Jesus to her, “behold thy son!” St. John was this son, and he represented all mankind.

The Holy Ghost now infuses into Mary the plenitude of the grace needful for her maternal mission. From this day forward, she acts as Mother of the infant Church; and when, at length, the Church no longer needs her visible presence, this Mother quits the earth for heaven, where she is crowned Queen; but there, too, she exercises her glorious title and office of Mother of men.2

In this depiction of Pentecost, the apostles all react upon being "filled with the Holy Spirit" in an individualized way; however, the presence of Mary, mother of the Church, in the center of the painting unites their personal experiences in her prayer. Her gaze upon the Spirit is closest and most direct. She receives his light most fully and receptively.

The presence of the "rushing mighty wind” is visible in the ecstatic movement of the apostles and their clothing. Swaying hands and off-balance bodies seem blown about. At the same time, the dove, an image of the Holy Spirit from Christ’s Baptism, seems to hold the figures in balance. The outstretched wings of the hovering bird seem to represent the God’s providence, holding all things together in love.

El Greco's expressionistic style and mystical bodies call our attention to the spiritual transformation and movements of the soul that are the work of the Holy Spirit. The artist gives us a visual image of how, as Saint Basil says, “the Spirit is manifold in his mighty work.”

Pentecost reminds us of the role of the Spirit in the Church and in the sacraments. As Saint Didymus of Alexandria writes in his treatise on the Holy Spirit and Baptism,

The Spirit frees us from sin and death, and changes us from the earthly men we were, men of dust and ashes, into spiritual men, sharers in the divine glory, sons and heirs of God the Father who bear a likeness to the Son and are his co-heirs and brothers, destined to reign with him and to share his glory.3

Perhaps drawing on the liturgy, El Greco especially draws attention to the role of the Spirit as the Illuminator. The apostles all shine with a luminous radiance. This radiance reminds me of what Saint Basil speaks of when he says:

As clear, transparent substances become very bright when sunlight falls on them and shine with a new radiance, so also souls in whom the Spirit dwells, and who are enlightened by the Spirit, become spiritual themselves and a source of grace for others.4

In the Pentecost liturgy, The “Golden Sequence,” known as the “Veni, Sancte Spiritus” especially highlights the magnificent and transformative light of the Holy Spirit who continues to renew the Church and our souls.

One apostle, thought to be a self-portrait of El Greco, looks out and directly confronts the viewer, reminding us to continue to call upon the Holy Spirit to guide our steps, enlighten our hearts, and purify our souls. The Church gives us such a prayer in the ancient Pentecost sequence:

Come, Holy Spirit, come!

And from your celestial home

Shed a ray of light divine!Come, Father of the poor!

Come, source of all our store!

Come, within our bosoms shine.You, of comforters the best;

You, the soul's most welcome guest;

Sweet refreshment here below;In our labor, rest most sweet;

Grateful coolness in the heat;

Solace in the midst of woe.O most blessed Light divine,

Shine within these hearts of yours,

And our inmost being fill!Where you are not, we have naught,

Nothing good in deed or thoughts,

Nothing free from taint of ill.Heal our wounds, our strength renew;

On our dryness pour your dew;

Wash the stains of guilt away.Bend the stubborn heart and will;

Melt the frozen, warm the chill;

Guide the steps that go astray.On the faithful, who adore

And confess you, evermore

In your sevenfold gift descend;Give them virtue's sure reward;

Give them your salvation, Lord;

Give them joys that never end.Amen. Alleluia.5

The first novena. Jews at this time celebrated Pentecost 50 days after Passover. The festival celebrated God revealing the Law to Moses on Sinai and the end of harvest. It also looked forward to God’s return to the temple.

Dom Prosper Gueranger, The Liturgical Year, vol. 9., p. 295

From the Didymus of Alexandria’s treatise On the Trinity: The Holy Spiritrenews us in baptism. (Lib. 2, 12: PG 39, 667-674)

Read in the Office of Readings during the sixth week of Easter.

From Saint Basil’s treatise on the Holy Spirit. (Hom. 15: Jaeger VI, 466-468)

https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/3203.htm

Read in the Office of Readings during the Seventh Week of Easter: https://divineoffice.org/easter-w07-tue-or/

Veni, Sancte Spiritus,

et emitte caelitus

lucis tuae radium.

Veni, pater pauperum,

veni, dator munerum,

veni, lumen cordium.

Consolator optime,

dulcis hospes animae,

dulce refrigerium.

In labore requies,

in aestu temperies,

in fletu solatium.

O lux beatissima,

reple cordis intima

tuorum fidelium.

Sine tuo numine,

nihil est in homine,

nihil est innoxium.

Lava quod est sordidum,

riga quod est aridum,

sana quod est saucium.

Flecte quod est rigidum,

fove quod est frigidum,

rege quod est devium.

Da tuis fidelibus,

in te confidentibus,

sacrum septenarium.

Da virtutis meritum,

da salutis exitum,

da perenne gaudium.

I just came back from practicing today’s hymns on the organ and had time to read this before heading back to church shortly. A perfect way to prepare for Pentecost! What a remarkable painting. Thanks, Amelia!

Such a great blessing after Mass! As I sip coffee and ponder these skillfully displayed words and images my appreciation for the 'gift' of your ART WORK grows deeper.

Besides El Greco's vivid RGB colorization of principle figures (prefiguring our modern understanding of the primacy of RGB optical light) these visions once engaged, are modes of spiritual transport.

Hiss sublimely rendered hands are amazingly beautiful and expressive. They act!

And then there is the other feature that jumped out, or should I say caved in. The Christ Child's belly button was very obvious and then I started seeing some of the others. It made me chuckle at first. BUT then I spied the baby lamb, tied and motionless at Mary's feet.

Then I thought the vine...abiding...the branches...the fruit of the vine...mystical body, navel, the umbilical cord...new life.

Deep truth for sure.