I’ve noted before that paintings of conversion are a baroque specialty. The Calling of Saint Matthew is the iconic baroque painting of conversion. However, it is not meant to be viewed alone. It hangs in San Luigi, the French National Church in Rome, across from Saint Matthew's Martyrdom and beside The Inspiration of Saint Matthew.

Conversion and martyrdom were intimately connected in the Catholic baroque imagination—indeed conversion and death are bound together in every Christian life—but it’s rare to see an artist pair these events as dramatically and directly as Caravaggio does.

Unsurprisingly, The Calling is the most popular of the three paintings. Whether it’s the best painting is debatable, but it’s certainly more palatable, especially for our modern sensibilities which shy away from death. It is a profound piece to meditate on alone, but even more so when contemplated with the other paintings in the Contarelli Chapel.

The chapel was Caravaggio’s first church commission and the first time he paired conversion and martyrdom—but certainly not the last1. Before this, he painted small genre scenes. One theme he had returned to multiple times was the souring of youthful hedonism. In the portraits below, he painted muscular boys adorned with rotten fruit, whose eyes reveal a kind of disillusionment with the excess. It’s fitting that after painting these portraits, Caravaggio moved to depicting conversion.

In The Calling, light descends on a dark street corner where Matthew sits amidst his foppishly dressed cronies. Some of the boys appear to be characters from Caravaggio’s earlier paintings. He leaves a seat open at the end of the table, inviting us to imagine ourselves in the Biblical story, as Saint Ignatius invites us to do in the Spiritual Exercises.

As Jesus went on from there, he saw a man named Matthew sitting at the tax collector’s booth. “Follow me,” he told him, and Matthew got up and followed him. (Matthew 9:9)

For the entourage at the table and for us, Jesus is just beginning to emerge from the shadows. He’s marked by a faint halo and seems to bring the light with him. The light is warm with a golden hue, and appears to grow slowly, gently pushing out the darkness.

Jesus and Peter’s austere robes, which seem ancient, clash with the flamboyant 16th-century outfits of the men at the table. This contrast sets them apart from those at the table. With this detail, Caravaggio reminds us that God became man at a specific moment in time but that he continues to make himself known in every age.

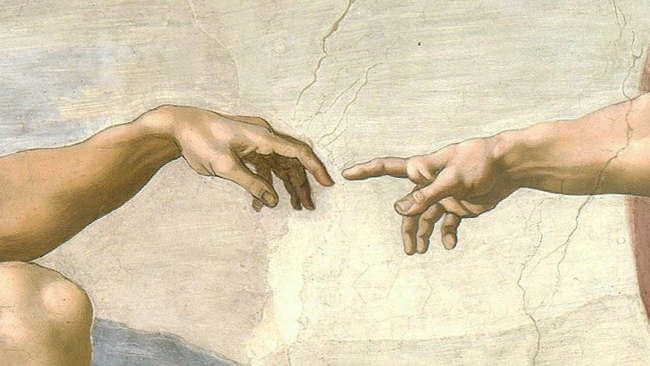

Pointing limply, Jesus looks directly at Matthew. Christ’s finger echoes the hand of Adam, painted by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel. Here, Christ is the new Adam, who has taken on human flesh and will make all things new, “The first man, Adam, became a living being; the last Adam became a life-giving spirit” (1 Corinthians 15:45) Peter stands next to Jesus, mimicking his pose, suggesting Peter’s role in directing new Christians to the Church.

But which figure in the painting is Matthew? He’s not identified by a halo, which creates a little ambiguity. Nevertheless, Matthew can be identified, and Caravaggio uses light and gesture to reveal him. The light from the corner illuminates the apostle’s face, like the light of divine illumination. The light allows us to see Matthew and allows Matthew to see the face of Christ. The tax collector points to himself with a surprised but interested look. Although he appears a little incredulous, his legs shift as if he is already starting to stand upright.

The two boys closest to Jesus and Peter look like they have seen the light, while the boy at the end of the table and the older man with the spectacles hardly seem to notice the God-man pointing in their direction.

The painting is a call to conversion and to attentiveness. Caravaggio shows us the perils of inattention. If we, like the younger man at the end of the table, can not look away from our phones, money, or ego, we can’t follow Christ. The biblical verse and the painting convey a sense of urgency to Christ’s call.

Some modern scholars argue that Matthew is the younger man at the end of the table, but as Elizabeth Lev argues, this is not Caravaggio’s style.2

“Caravaggio’s most important characteristic, besides his dramatic use of light, was his penchant for capturing the culminating instant on canvas.”—Elizabeth Lev

Caravaggio was more of a spiritual dramatist than a realist. He used staging and lighting to tell a story and reveal spiritual truth. His gritty “realistic” details, like dirty feet, were not done simply for the sake of realism. Caravaggio included these kinds of details to emphasize the way Jesus uplifts the lowly and transforms humiliation and poverty into blessedness.

This middle painting, which hangs above the chapel altar, was painted last and ties the themes of conversion and martyrdom together. The black atmosphere gives Matthew’s body a sculptural heaviness, and the teetering stool pulls us into the scene. Matthew looks above for inspiration, consulting with angels as he writes his Gospel. The bright red orange of his robes imitates a flame, reminding us that the Holy Spirit works through him as he writes. This painting also reminds us that between conversion and martyrdom, Matthew continued to turn to God in prayer, nourishing his spirit, preparing for death.

As Pope Benedict XVI once remarked,

Once again, where does the strength to face martyrdom come from? From deep and intimate union with Christ, because martyrdom and the vocation to martyrdom are not the result of human effort but the response to a project and call of God, they are a gift of his grace that enables a person, out of love, to give his life for Christ and for the Church, hence for the world.

The Golden Legend provides an account of Matthew’s death. In the story, Matthew tried to forbid the Ethiopian king from marrying his niece, who had committed herself to God as a Virgin. Enraged, the Ethiopian King sent a swordsman “who came behind Matthew as he stood at the altar with his hands raised to Heaven in prayer, drove his sword into his back, and so consummated the apostle’s martyrdom”

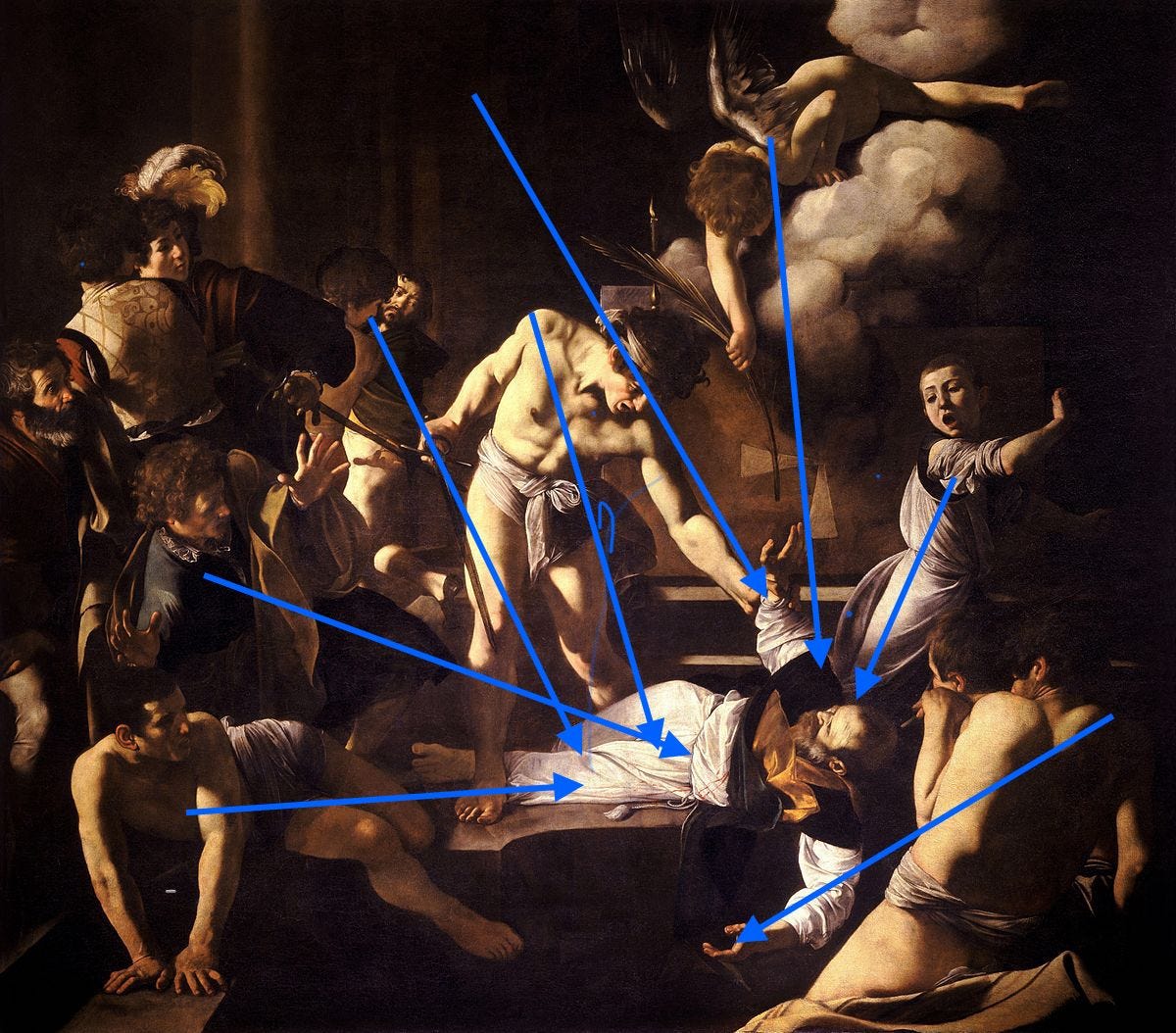

Amidst the chaos of Caravaggio’s scene, Matthew appears to accept death with open arms. His arms mirror the open arms of the Angel creating a visual harmony amidst the frenzied scene. A dizzying array of figures bolt away from the violent murder.

Our attention is first drawn to the lit body of the executioner and the horrified expressions of the people in the crowd. A young boy screams in terror. Potential neophytes clad in loincloths awaiting baptism contort their bodies so they do not fall into the baptismal pool before the altar. Others look on in shock and shame. Caravaggio paints himself looking quite perplexed, identifying himself with those who flee in disgrace.

Here, Caravaggio inverts the Renaissance pyramidal composition into Vs and Xs. In doing this, Caravaggio shows how God invades our world through the incarnation and continues to reach down to us. We do not build the way to heaven. Our role is to respond.

No matter where we look in the painting, Caravaggio pulls our attention back to the saint, who lies splayed on the floor wearing a black chasuble. Like Christ, it is in his humiliation and death that he is exalted. While others flee in terror, Matthew alone sees the angel who reaches down to give him the palm of martyrdom.

Blood from Matthew’s side drips into the baptismal pool below, reminding us that, like baptism, martyrdom is a rebirth that participates in Christ’s death and resurrection.3 As Paul says in Romans:

Do you know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death, so that as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life.(Romans 6:3-4)

By putting Matthew’s conversion together with his martyrdom, Caravaggio reminds us of the cost of conversion, of the things we must put to death to truly turn to Jesus. In Matthew’s case, the cost of conversion was martyrdom. In our cases, it’s usually more minor deaths to self, but ultimately death comes to us all. The Martyrdom is also a momento mori, a reminder of our own death.

Although the painting may seem a little grim and gloomy, the triumphant architecture of San Luigi lifts us back up, reminding us that Saint Matthew lives today with Christ in the Heavenly Jerusalem.

What strikes you about these paintings? What details do you notice?

The Conversion of Paul and the Crucifixion of Saint Peter hang across from each other in the Cerasi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo

This theory has become popular in the past 30 years but was pretty much non-existent previously. For more discussion on this: https://www.italianinsider.it/?q=node/6835

Baptismal pools were common in the Early Church and survived still in 16th century Milan where Caravaggio grew up.

“Caravaggio shows us the perils of inattention. If we, like the younger man at the end of the table, can not look away from our phones, money, or ego, we can’t follow Christ.”

Convicting and insightful piece. Thank you!

Thanks for this insightful analysis. Caravaggio's works are a good reminder that we shouldn't reduce Western art history to a false dichotomy between the spiritual/symbolic/mystical art of the Middle Ages and the secularism/naturalism/realism of the Renaissance. The Calling of Saint Matthew and The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew are rich visual texts that are realistic, yes, but also dramatic, engaging, aesthetically refined, and profoundly spiritual.