“The allotted function of art is not, as is often assumed, to put across ideas, to propagate thoughts, to serve as an example. The aim of art is to prepare a person for death, to plough and harrow his soul, rendering it capable of turning to good.”—Andrei Tarkovsky

"But, my dear Sebastian, you can't seriously believe it all."

"Can't I?"

"I mean about Christmas and the star and the three kings and the ox and the ass."

"Oh yes, I believe that. It's a lovely idea."

"But you can't BELIEVE things because they're a lovely idea."

"But I DO. That's how I believe.”

In this conversation from the great 20th century novel Brideshead Revisited, Charles Ryder, the agnostic narrator, presses his Catholic friend, Sebastian Flyte about the nature of faith. Sebastian’s faith confounds Charles’s rationalist presuppositions.

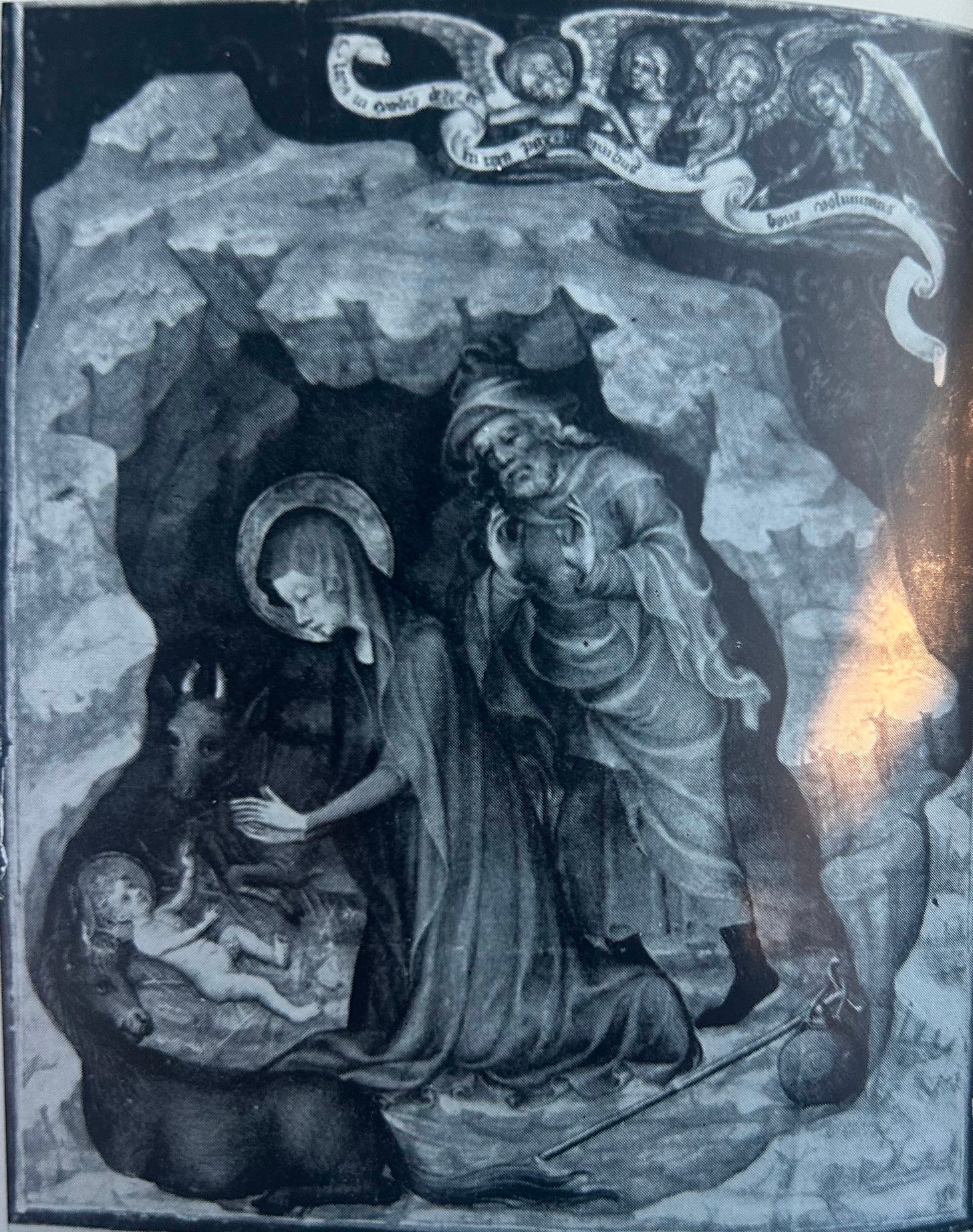

The story of Christ’s birth continues to confound and charm. But is the artistic tradition which includes the ox and the ass and the star and stable really trustworthy or should we, as some scholars would recommend, “rewrite our Christmas songs” and “take down our creche scenes?”1

In this article, I will argue that far from obscuring what “really happened” on the night of Christ’s birth, the artistic tradition enriches our appreciation and understanding of the event of Christ’s birth. There is more truth than we know in the paintings of Jesus born in the stable with the ox and the ass, not less.

“And she brought forth her firstborn son, and wrapped him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a manger; because there was no room for them in the inn.” Luke 2:13

Although it only occupies a few lines in the Bible, the Nativity is perhaps the most painted image in Christian art. Part of the reason for its centrality is its beauty and charm. That God came into his creation as a frail and humble baby is an amazing thing. Of course, for rationalists there’s always something suspicious about beauty. In this view, things are more true when they are dissected or deconstructed, and examined for their individual parts. In this rationalist credo, something that is poetic is less likely to be true. This is not so in Christian tradition where we believe beauty is a transcendental that actually helps us come to know the truth. As Pope Benedict XVI once said:

The encounter with the beautiful can become the wound of the arrow that strikes the heart and in this way opens our eyes, so that later, from this experience, we take the criteria for judgment and can correctly evaluate the arguments.2

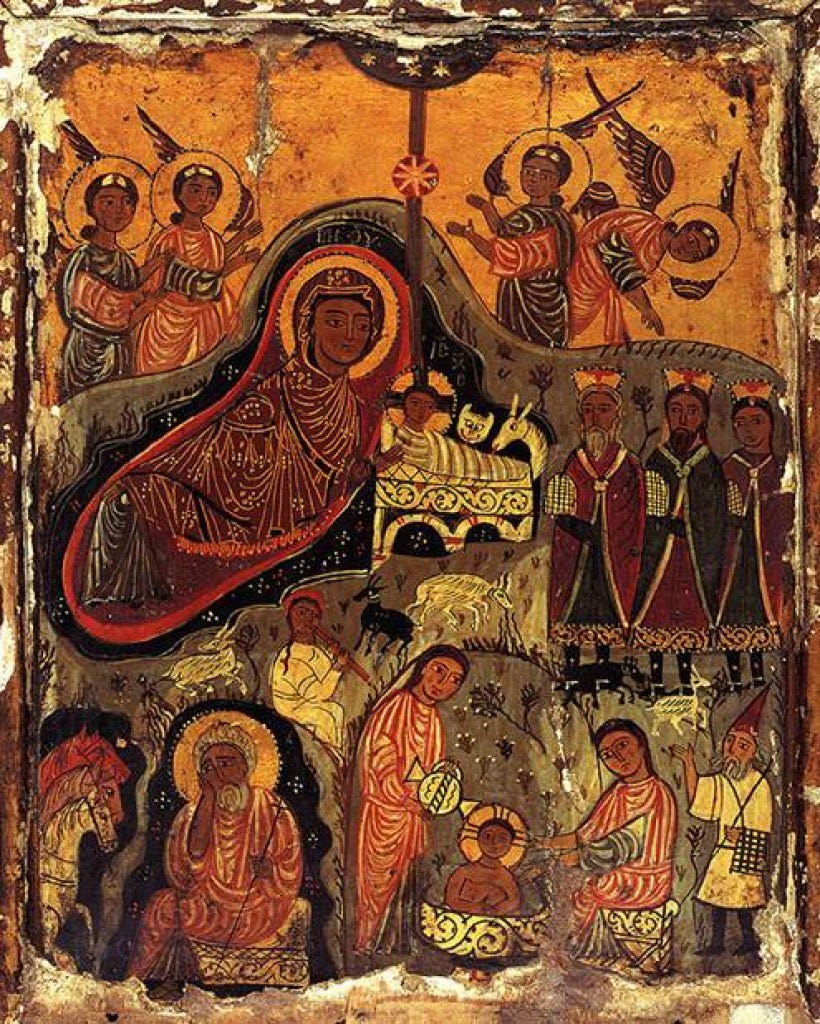

The loveliness of the Christmas songs and images is part of what makes them so enduring, but the animals and the stable are far from mere sentimental ornamentation. For early Christians, the ox and ass signified that Jesus fulfilled the prophecies. Origen explained that Jesus’s manger “was that very one, which the prophet foretold, saying, ‘The ox knoweth his owner, and the ass his master’s manger’” (Isaiah 1:3) and “Between two animals you are made manifest” (Habakkuk 3:2).

The Church Fathers understood the ox as the Jews, weighed down by the law, and the unclean donkey as the Gentiles, weighed down by the sin of idolatry. The image of these two animals together represent the way Christ came to be King of all peoples. Oftentimes the ox and ass are depicted feeding on the hay in the manger or licking the Christ child, symbolizing how the faithful feed on the body of Christ in the Eucharist.3

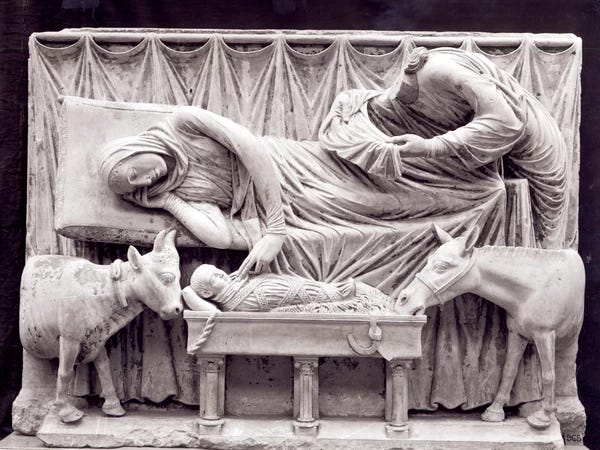

The great art historian, Gertrud Schiller, explains the meaning of these early Nativity scenes, often carved on a sarcophagus, which may seem crude to our modern eyes: “Christ lying in the manger signifies no less than this: the Divine King has entered the world in all its poverty in order to save it.”4

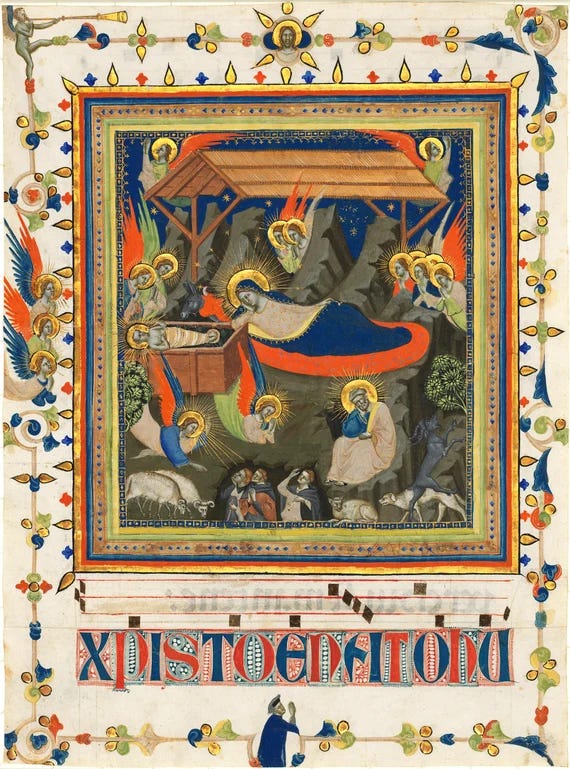

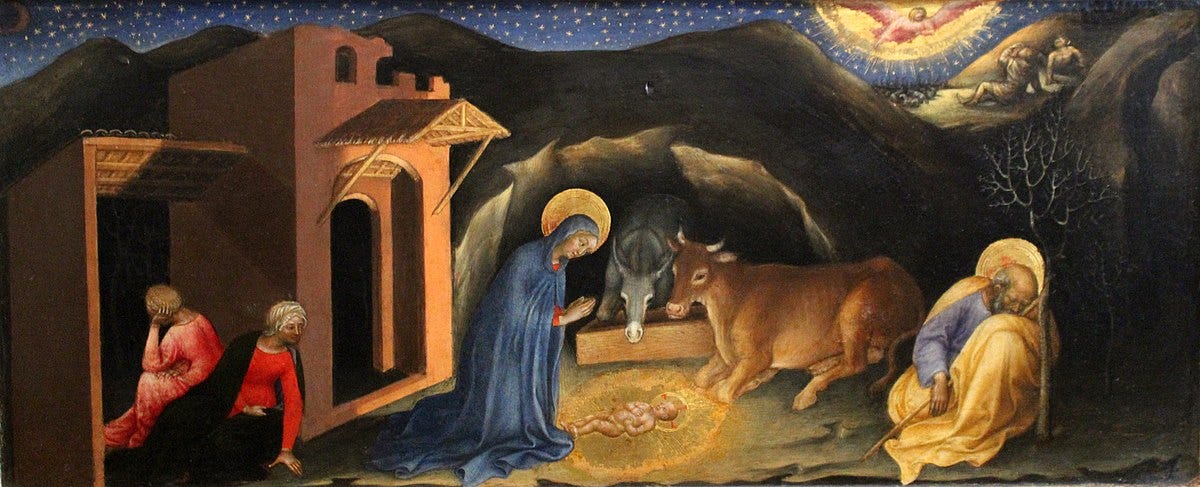

Nativity art continued to blossom in the East as a fruit of the great Christological Councils, which clarified that Jesus was both fully God and fully man. After the Council of Ephesus in 431 AD, which taught that Mary was the mother of God, Mary became more prominent in images of the Nativity. By the seventh century, a cave had become part of the standard icon of the Nativity. Although a stable or cave is not mentioned in the Bible, we know from Church Fathers Justin Martyr, Origen, and Jerome, that as early as the first century, Christians formed a church on what was known to be the cave of Christ’s birth. You can still visit this spot today. It is the oldest continuously used Church in the world.

Justin Martyr, the great Christian apologist of the second century, was born just 30 miles north of Bethlehem less than 100 years after the death of Christ. He recounts how Christ was born in a cave which was used as a stable:

But when the Child was born in Bethlehem, since Joseph could not find a lodging in that village, he took up his quarters in a certain cave near the village; and while they were there Mary brought forth the Christ and placed Him in a manger, and here the Magi who came from Arabia found Him.5

Origen in 235 AD:

With respect to the birth of Jesus in Bethlehem, if anyone desires to have additional evidence, there is shown in Bethlehem the cave where he was born, and the manger in the cave where he was wrapped in swaddling clothes. And this sight is greatly talked of in surrounding places, even among the enemies of the faith. It is being said that in this cave was born that Jesus who is worshipped by Christians.6

Origen goes on to describe how in the early second century the emperor Hadrian, in an attempt to discourage Christian worship, built a temple to Venus over the cave of Christ’s birth. The temple ended up having the opposite effect Hadrian intended. For Christians, the temple preserved the memory of the Nativity’s location, so that when Constantine became emperor, his mother Saint Helena was able to visit the cave and build a church over it. Shortly after this, Saint Jerome made a pilgrimage to the cave of the Nativity in 385 AD and was so moved that he took shelter in the adjacent cave for almost 40 years while translating the Vulgate.

Pilgrims still visit the Church of the Nativity today, and archeologists have recently discovered that the dates of the first church correspond with Origen and Justin Martyr’s account. From their study and from the accounts of the Church Fathers, we know Bethlehem was dotted with caves inhabited by people and animals. In fact, people still dwell in caves in the area surrounding Bethlehem.7

So the artistic tradition, that Christ was born in a cave amidst animals, is based on a trustworthy account. But the cave is also a symbolically pregnant image which invites rich contemplation. Indeed the cave of Christ’s birth is hidden and dark, like the womb of Mary in which he spent nine months of his life. In this sense, the cave is a spiritually generative place. Amidst the rugged inhospitable terrain of the mountain, or the world of sin, the cave is a “place of mercy and protection.”8

In the Bible, David, Elijah, and Daniel found refuge in a cave. The 100 prophets of Obediah also found shelter from the wrath of Jezebel in a cave.

Christ came into a world shrouded in sin and darkness and was born in a cave, the darkest place on earth, at the darkest, bleakest time of year. His birth in a cave invites us to contemplate how the Light of the World came to bring light to even the darkest corners of the earth, and indeed his light can shine even in the darkest parts of our life.

Caves also remind us of death because of their darkness and their function as a place for burial. Thus, the circumstances of Jesus’s birth also foreshadow his death. The swaddling cloth reminds us of his burial cloth, the wooden casket-like manger of the cross, and the cave itself of his tomb. It is the divine condescension into the darkness of man’s sin on earth, to the point of death and even beyond, for the cave of his birth also prefigures his baptism and his descent into Hades itself. When Christ took on humanity, he also took on death, chaos, Satan, and the forces of darkness.

The great paintings of the Western tradition and icons of the Eastern do not allow us to contemplate Christ’s birth without thinking of his saving death. But, of course his death is not the end, for from the cave of his burial Christ emerged victorious over death.

As Jonathan Pageau wrote:

And so although the cave is the image of death, it is not only an image of death, but also an image of that space within death, that opening of sacred space which contains the hidden treasure. It is the heart, the monk's cell, the holy of holies all at once. It is the place at the bottom of the baptismal font where we shed in fact death though we are immersed in it, where is found that seed, that divine spark which can then transform death into glory.9

In his Life of Paula, Saint Jerome remembers what Paula, the Roman aristocrat turned nun, exclaimed when she first saw the place of Christ’s birth. “I salute thee, Bethlehem, House of Bread, where bread was born that came down from heaven.”10

The “bread that came down from heaven” into the manger of the animals in Bethlehem — which means “house of bread” in Hebrew and “house of flesh” in Aramaic —comes down still on the altar in the liturgy. Fittingly, the manger is often depicted to resemble an altar reminding us of the sacrifice of Christ’s death which is commemorated in the Mass.

Although the cave is more standard in Eastern iconography than it is in Western painting, the cave is by no means foreign to Western art. It appears in some of the most famous Nativity paintings, including those by Duccio, Giotto, Fra Angelico, Botticelli, and Phillippe De Champaigne.11 In Christian art, the cave is actually the most consistently depicted place of Jesus’s birth.

Although we may be drawn to the Nativity because of its sheer beauty and loveliness, as Sebastian is, if we look long enough, we will see “a child embraced by death, and embracing death.”12 Yet, the Nativity is a reason for joy because that child is God himself and his death saved us from death. He lights not only the darkness of the cave, but the darkness of the world and the darkness of our own hearts. Because of this, we can become an icon of the cave of Christ’s birth as we prepare to receive him on Christmas and when he comes again.

Merry Christmas!

In his book Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes, late Presbyterian minister, Kenneth Bailey, claims that Jesus was born in a house rather than an isolated stable or cave. This theory has become quite popular in some protestant circles. In his understanding “inn” is better translated as “guest room.” Because of Middle Eastern hospitality and archeological evidence of houses in Bethlehem, Bailey assumes that Mary and Joseph were not turned away but welcomed into the main living space by Joseph’s family. So he concludes, Jesus was not born in a “cold, lonely stable” but a “warm and friendly home.” (Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes. Cultural Studies in the Gospel (2008)

Part of Bailey’s thesis rests on the idea that Joseph’s family in Bethlehem would not have turned them away because it would have been shameful. But, isn't this the point? It was shameful that Jesus was not received at his birth, and it was shameful that his own people sentenced him to death, especially by crucifixion. There are scholars much better studied than me who have refuted his newly popular theory. I find it odd that he assumes that the church fathers who lived in the area and were consummate greek scholars would misunderstood the meaning of this passage.

Read more here: https://rorate-caeli.blogspot.com/2022/12/christmas-why-birth-of-jesus-in-poor.html

https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_20020824_ratzinger-cl-rimini_en.html

More on this: https://www.newliturgicalmovement.org/2012/01/ancient-origins-of-nativity-scene-part.html?m=1

Schiller, Gertrud. 1971. Iconography of Christian Art. Translated by Janet Seligman. First American edition. Greenwich, Connecticut: New York Graphic Society Ltd, p. 49

https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf01.viii.iv.lxxviii.html

https://ccel.org/ccel/origen/against_celsus/anf04.vi.ix.i.lii.html

https://m.jpost.com/archaeology/jesus-birthplace-became-a-pilgrimage-site-earlier-than-previously-thought-653156

Schiller, 51

https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/the-cave-in-the-nativity-icon/

https://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2018/01/life-of-saint-paula-of-rome-st-jerome.html?m=1

Although the hut-stable eventually became more common in western art than the cave-stable because Europeans used huts to keep their animals rather than caves, the cave persisted.

https://orthodoxcityhermit.com/tag/nativity-icon/

Amelia, thank you for the background commentary and especially the many gorgeous images. Merry Christmas to you and yours!

Yesterday and I think the day before too, something seemed to be bubbling to the surface in my mind, a vague awareness, an important insight, yet not fully formed, still out of my reach. It was this that you wrote, exactly this: "Of course, for rationalists there’s always something suspicious about beauty. In this view, things are more true when they are dissected or deconstructed, and examined for their individual parts. In this rationalist credo, something that is poetic is less likely to be true. This is not so in Christian tradition where we believe beauty is a transcendental that actually helps us come to know the truth." Bless you!