In these two Maurice Dennis paintings, the Sacred Heart of Jesus bursts forth with Heaven's light amidst the darkness and suffering of the Crucifixion. A French painter and a faithful Catholic, Denis was devoted to his wife and seven children, whom he often featured in his art. His flat painting style has an intimate glow, reminiscent of icons, and brings forth the interior life of his subjects.

Denis was also an intellectual painter and wrote numerous books on aesthetics and even a history of art. He helped found the Nabis and Symbolist movements, which re-engaged spiritual and historical subjects after the Impressionists focused on more mundane subjects and scenes of nature.

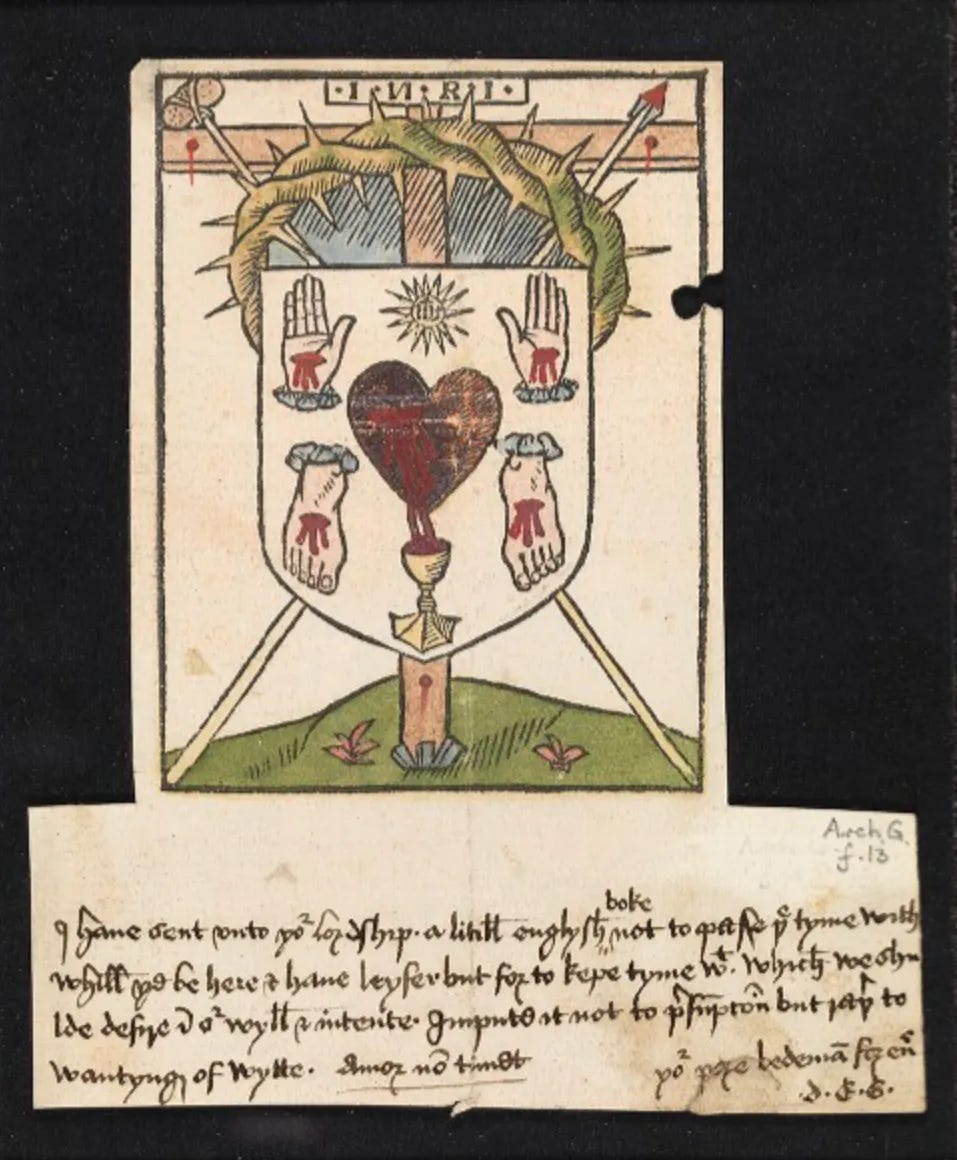

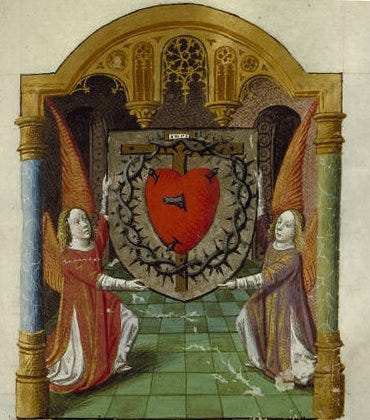

Although his two paintings of the Sacred Heart seem to depart from popular imagery—a longer haired Jesus holding his heart outside of his body— they harken back to the devotion's roots—when Longinus pierced Jesus’s Heart on the Cross. “One of the soldiers pierced his side with a spear, and at once there came out blood and water” (Jn 19:34). The Patristic Fathers understood the side wound to be the heart of Christ, a sign of his love, as did many medieval saints, including Saint Albert the Great (1206-1280), who spoke of the connection on numerous occasions1:

The water from his side and that which he poured from his Heart are witnesses of his boundless love.

His side in which rest all the riches of God's knowledge and wisdom; he showed his Heart, which had already been wounded by his love for us before it was struck by the point of the lance.

Why was he wounded on the side near his Heart? In order that we may never tire in contemplating his Heart.

By the blood of his side and of his Heart, our Lord watered the garden of the Church, for with this blood he made the sacraments flow from his Heart.2

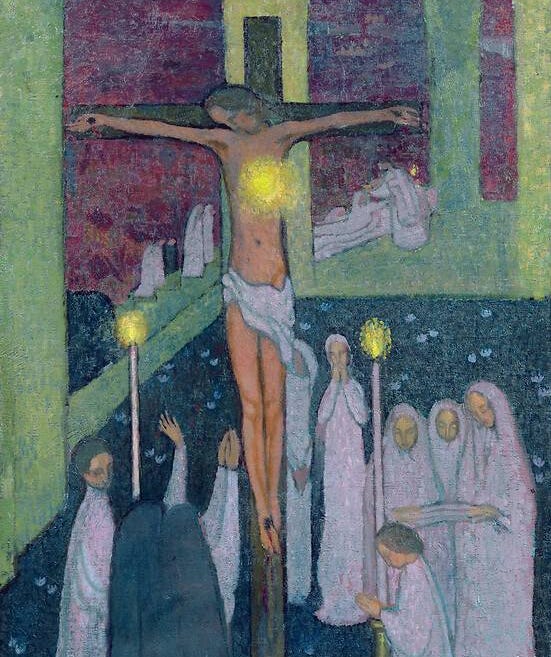

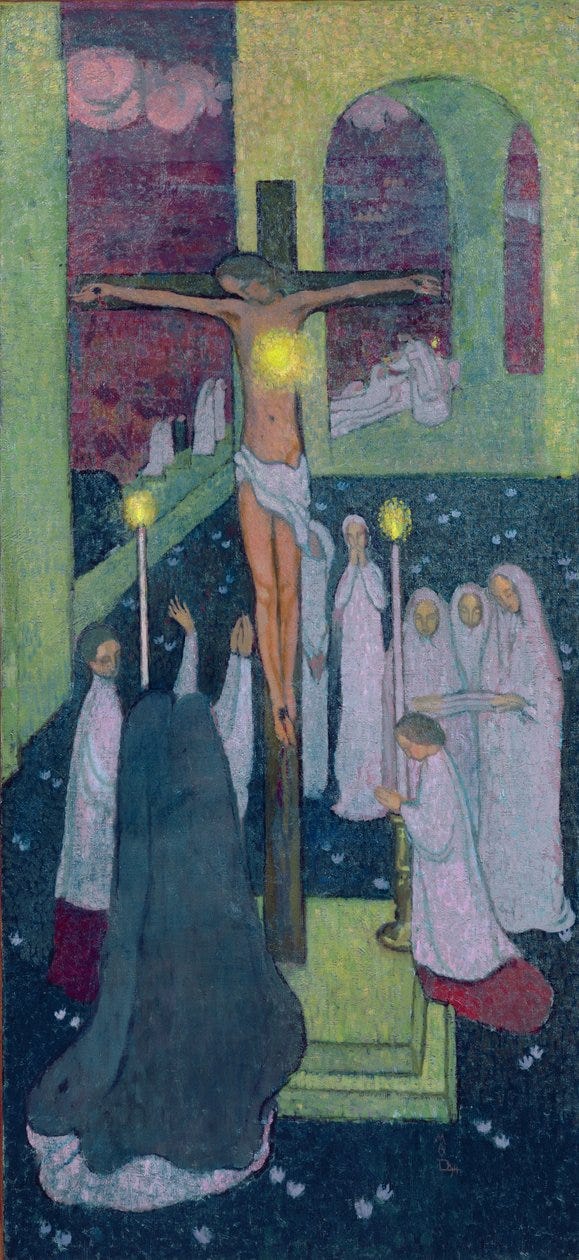

In his own painting, Denis seems to draw upon early artistic representations of the Sacred Heart which were tied to the popular medieval devotion to the five wounds of Christ. Denis’ painting “Crucified Sacred Heart,” connects the Heart of Jesus to the Cross and the Eucharist.3 The painting is almost abstract, but still intimate and representational. Mary Magdalene and the Blessed Mother stand at the feet of the Cross, their arms outstretched in anguish. Behind the Cross, three women clothed in white habits seem to sing prayerfully.

O most Sacred Heart, most loving Heart of Jesus, Thou art concealed in the Holy Eucharist, and Thou beatest for us still. Now as then Thou sayest, Desidero desideravi - "with desire I have desired." I worship Thee then with all my best love and awe, with my fervent affection, with my most subdued, most resolved will. O my God, when thou dost condescend to suffer me to receive Thee, to eat and drink Thee, and Thou for while takest up Thy abode within me, O make my heart beat with Thy Heart. Purify it of all that is earthly, all that is proud and sensual, all that is hard and cruel, of all perversity, of all disorder, of all deadness. So fill it with Thee, that neither the events of the day nor the circumstances of the time may have power to ruffle it, but that in Thy love and Thy fear it may have peace- John Henry Newman, (Meditations and Devotions, pp. 373-74).

In this painting, Denis provides a visual link between the feast and what happens on Good Friday. As Corpus Christi is a happy recapitulation of the institution of the Eucharist on Holy Thursday, the feast of the Sacred Heart is a recapitulation of Good Friday.4 So as Holy Thursday and Good Friday are linked together, Corpus Christi and The Feast of the Sacred Heart are also linked.

When Christ appeared to Sr. Margaret Mary Alacoque in 1675, he requested this:

I ask of you that the Friday after the Octave of Corpus Christi be set apart for a special Feast to honor My Heart, by communicating on that day, and making reparation to It by a solemn act, in order to make amends for the indignities which It has received during the time It has been exposed on the altars. I promise you that My Heart shall expand Itself to shed in abundance the influence of Its divine love upon those who shall thus honor It, and cause It to be honored.5

Although modern, Maurice Denis’ depiction of the Sacred Heart, very clearly connects the devotion to Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross and the Eucharist. The presence of the altar servers at the foot of the Cross places the “Crucified Sacred Heart” in a liturgical context, illustrating how the reality of Christ’s sacrifice is made present during Mass.

In the painting, Denis paints the Crucifixion in an enclosed garden dotted with white flowers. The way he depicts the garden and the arches behind it is reminiscent of how his favorite painter, Fra Angelico, used enclosed gardens in his own paintings during the Renaissance.

By painting the Crucifixion in a garden, Denis connects the Cross to the Tree of Life in the Garden of Eden and reveals how Christ’s loving sacrifice and his resurrection re-open the Garden of Paradise for us. The altar servers remind us that we are brought back into the sacred garden during Mass.

Behind the scene of the Crucifixion, women clothed in white process up to a priest (or is it Jesus?) to receive Holy Communion on their knees under an arched building which opens to the garden of the Crucifixion. The arches are in some ways reminiscent of a church but the airy openness also gives the procession a sublimity amidst a dark purple background. This color is somber yet also a regal reminder that Christ is on his throne while on the Cross.

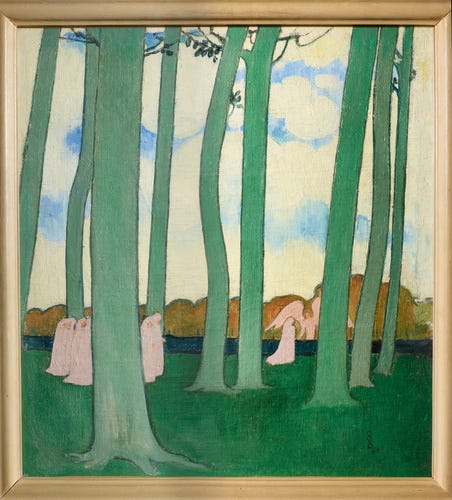

Denis often painted processions to symbolize our pilgrimage to heaven—as in the “Landscape with Green Trees” below— and the procession in “Crucified Sacred Heart” seems to fit that theme. The dark scene is bathed in a heavenly light emanating from the wounded Heart of Jesus, reminding us that when we partake in the Eucharist, we participate in the Heavenly Banquet and receive Jesus’s Sacred Heart.

The traditional post-communion oration also makes this connection explicit, as Dr. Michael Foley says, “boldly equating the act of Holy Communion with tasting the Heart of Jesus.”6:

May Thy holy mysteries, O Lord Jesus, impart to us divine fervor: whereby having tasted the sweetness of Thy most loving Heart, we may learn to despise earthly things and to love what is heavenly: Who livest and reig…”7

Denis also incorporates many of the epithets from the Sacred Heart litany . Behind the Cross, the Temple imagery reminds us that in the Crucifixion, Christ and his Sacred Heart become the “Holy Temple of God.” By partaking in the Eucharist, we also become a dwelling for God. When Jesus's side is pierced, water and blood flow as they do “from the right side of the temple” (Ezekiel 47:1).

The fire surrounding Jesus's wounded Heart reveals the intensity and power of Christ’s love. As Saint Catherine of Sienna (1347-1380) wrote, “Put your mouth at the heart of the Son of God, since it is a heart that casts the fire of charity and pours out blood to wash away your iniquities.”8

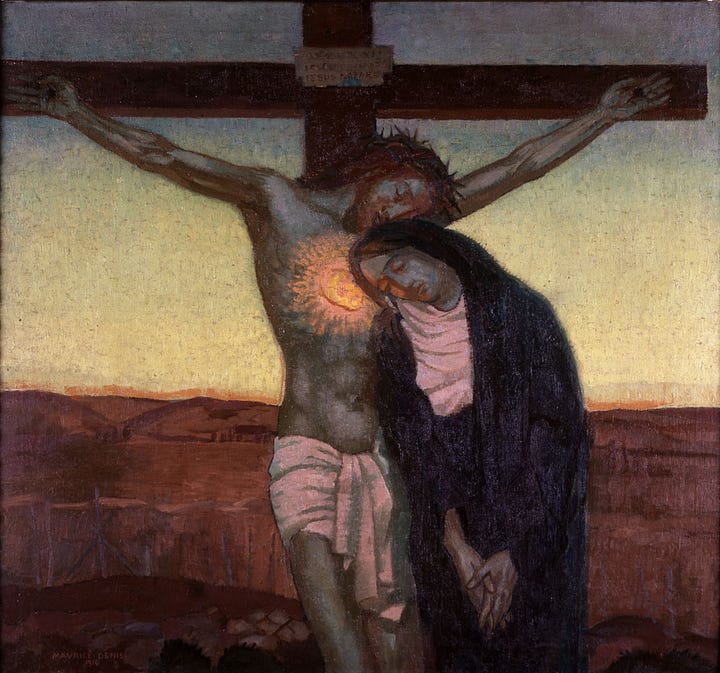

In the 1930 painting, where Mary rests her head on the heart of her son, Denis powerfully illustrates how the Sacred Heart is a refuge for our weariness and suffering. Here, Dennis illuminates the epithets from the litany: “Sharer in our sorrow,” “Acquainted with grief,” “Fountain of life and Holiness.”9

The way Jesus and Mary’s faces touch recalls the famous icon, the Virgin of Tenderness, which prefigures the sorrow of the Crucifixion. In Denis’s painting, Mary mourns and Jesus takes her underneath his breast and comforts her. Though his glowing Heart bears witness to his divine nature, his expressive face bears witness to the depths of his human suffering. Mary rests her head on the Sacred Heart of her Son, which glows with the passion of his divine sacrificial love. In this silent and sorrowful moment, cor ad cor loquitor, heart speaks to heart. Mary’s grief here shows us the deep union between her heart and the Heart of her Son, the Heart of God himself.

We are called with Mary to conform our own heart to his Sacred Heart, offering ourselves to him. Pope Leo XIII reminds us to do this:

And since there is in the Sacred Heart a symbol and a sensible image of the infinite love of Jesus Christ which moves us to love one another, therefore is it fit and proper that we should consecrate ourselves to His most Sacred Heart-an act which is nothing else than an offering and a binding of oneself to Jesus Christ.10

For history of the devotion see:

Timothy T. O'Donnell, Heart of the Redeemer: An Apologia for the Contemporary and Perennial Value of the Devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2017).

Joseph Campbell, 'Devotion to the Heart of Christ Before St. Margaret Mary, June 4, 2023, https://unamsanctamcatholicam.com/2023/06/04/devotion-to-the-heart-of-christ-before-st-margaret-mary/."

Timothy T. O'Donnell, p. 97-98

Michael Foley, “The Heart-Warming Orations of the Feast of the Sacred Heart," New Liturgical Movement, June 16, 2023, https://www.newliturgicalmovement.org/2023/06/the-heart-warming-orations-of-feast-of.html?m=1.

The Autobiography of St. Margaret Mary (Rockford, Ill: TAN edition, 1986), p. 106-107

Michael Foley, “, “The Heart-Warming Orations of the Feast of the Sacred Heart,"

Ibid

St. Catherine of Siena, Letters, 97

https://sacredheartsisters.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Litany_of_the_Sacred_Heart.pdf

Pope Leo XIlI, Annum Sacrum (Encyclical on the Consecration to the Sacred Heart, May 25, 1899), Vatican, https://www.vatican.va/content/leo-xiii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_I-xiii_enc_25051899_annum-sacrum.html.

for home enthronement see: https://www.sacredheartgr.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Home-Entrhonement-Booklet-with-Introduction-1.pdf

![Sacré-Cœur [de la Triennale], 1916 - next picture Sacré-Cœur [de la Triennale], 1916 - next picture](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!mgq6!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0b02bfc7-4da6-4582-813d-0b47c593e7cb_1000x935.jpeg)

Kinda want to take this into Eucharistic Adoration for meditation...is that so wrong?

Thank you for this post. I love the devotion, but I wonder why, why, why, do catholic artists continually depict Christ’s body as a teenage girl? It’s so inoffensive. It’s so delicate. It’s so safe. And, frankly I’m tired of these depictions. Jesus Christ was crucified naked, bloody and beaten, nailed to a crude cross in public at a crossroad, during a major holiday for all to see - but, where are the artists? Outside of Caravaggio, He is never depicted as having a real body - and why, why, why to add insult to injury, is He always wearing a diaper?